Approach Four:

Participatory Methods

These participatory approaches move away from creating outcomes to disseminate to consumers for interpretation, and instead are concerned with creating experiences which prompt reflection in consumers themselves. I use these participatory methods to test and confirm whether the stories and processes of experimentation from previous approaches can impact on consumers.

Experiment

Cultural probe

Aim

To design an experience in the form of a cultural probe that facilitates ecological and ontological self-reflection about plastics in consumers as participants. This process of self-led engagement with plastics is intended to guide participants to form their own intuitive and genuine responses to these plastics. It hypothesises that interacting with and being in the presence of these plastics will facilitate interest, exploration and ecological dialogue in participants.

Precedents

This experiment takes reflections from the conclusion of Approach Three: Speculative Stories—which asked whether asking consumers to write their own stories would be a more effective way of generating ecological shifts in perceptions regarding plastic—into its design.

Keri Smith’s How to be an Explorer of the World (2008) is also used as a precedent to inform the physical form and tone that this experiment takes.

Keri Smith’s How to be an Explorer of the World (2008) is also used as a precedent to inform the physical form and tone that this experiment takes.

Methods

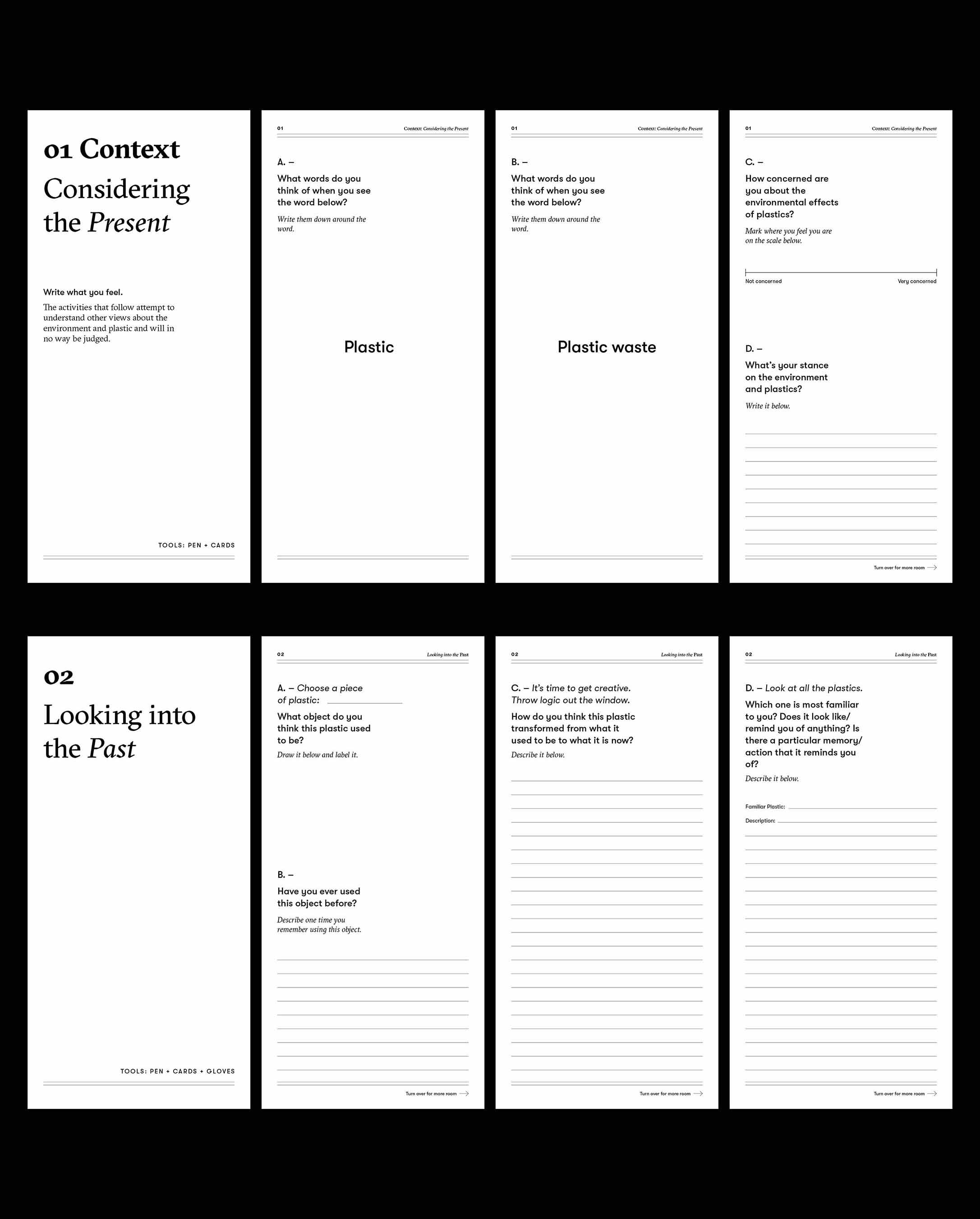

This probe re-appropriated processes from previous experiments into questions that sought to inspire similar concepts, ideas and thoughts in consumers. It framed questions around activities of observing, describing and forming analogies (from Approach One) to facilitate close engagement in participants with the warped plastics (Figure 47). It also built on ideas from Approach Three including speculative story generation about the future, custodianship and its fragmented storytelling structure and translated this into prompts (Figure 48).

These questions were packaged as a ‘kit’ of prompts that participants could follow and move through (Figure 47, 48 & 49). These prompts particularly sought to encourage physical interaction with the plastic, as it was my own exposure to these artefacts which brought forth deeper ecological considerations of how I relate to plastic waste. The lens of considering the past, present and future of plastics was a method to facilitate a process of reflection, building to an understanding of the deep time span of plastics.

These questions were packaged as a ‘kit’ of prompts that participants could follow and move through (Figure 47, 48 & 49). These prompts particularly sought to encourage physical interaction with the plastic, as it was my own exposure to these artefacts which brought forth deeper ecological considerations of how I relate to plastic waste. The lens of considering the past, present and future of plastics was a method to facilitate a process of reflection, building to an understanding of the deep time span of plastics.

Reflection

My return to physical interactions with the warped plastics as a method highlighted the importance of the tactility and materiality of these plastics in affecting responses.

However, there were too many activities included in this prompt, which reflected a confusion over what it was that I wanted to gain from participants, and what I wanted the outcomes to be. As a result of the amount of activities, the probe felt like a survey at times, and given the length of some of the activities, might have dissuaded participants from actively engaging.

However, there were too many activities included in this prompt, which reflected a confusion over what it was that I wanted to gain from participants, and what I wanted the outcomes to be. As a result of the amount of activities, the probe felt like a survey at times, and given the length of some of the activities, might have dissuaded participants from actively engaging.

Insights

A more streamlined probe—with emphasis on play and creativity—was needed.

Experiment

Creative probe

Aim

To create conditions for participants to creatively play with and respond to the warped plastic waste items as a method for facilitating individually generated ecological reflections.

Precedents

This probe is an iteration of the previous Experiment: Cultural probe, and focuses more heavily on using creative play and exploration to generate active and motivated responses from consumers. It once again draws on How to be an Explorer of the World (Smith, 2008) as an example of a cultural probe.

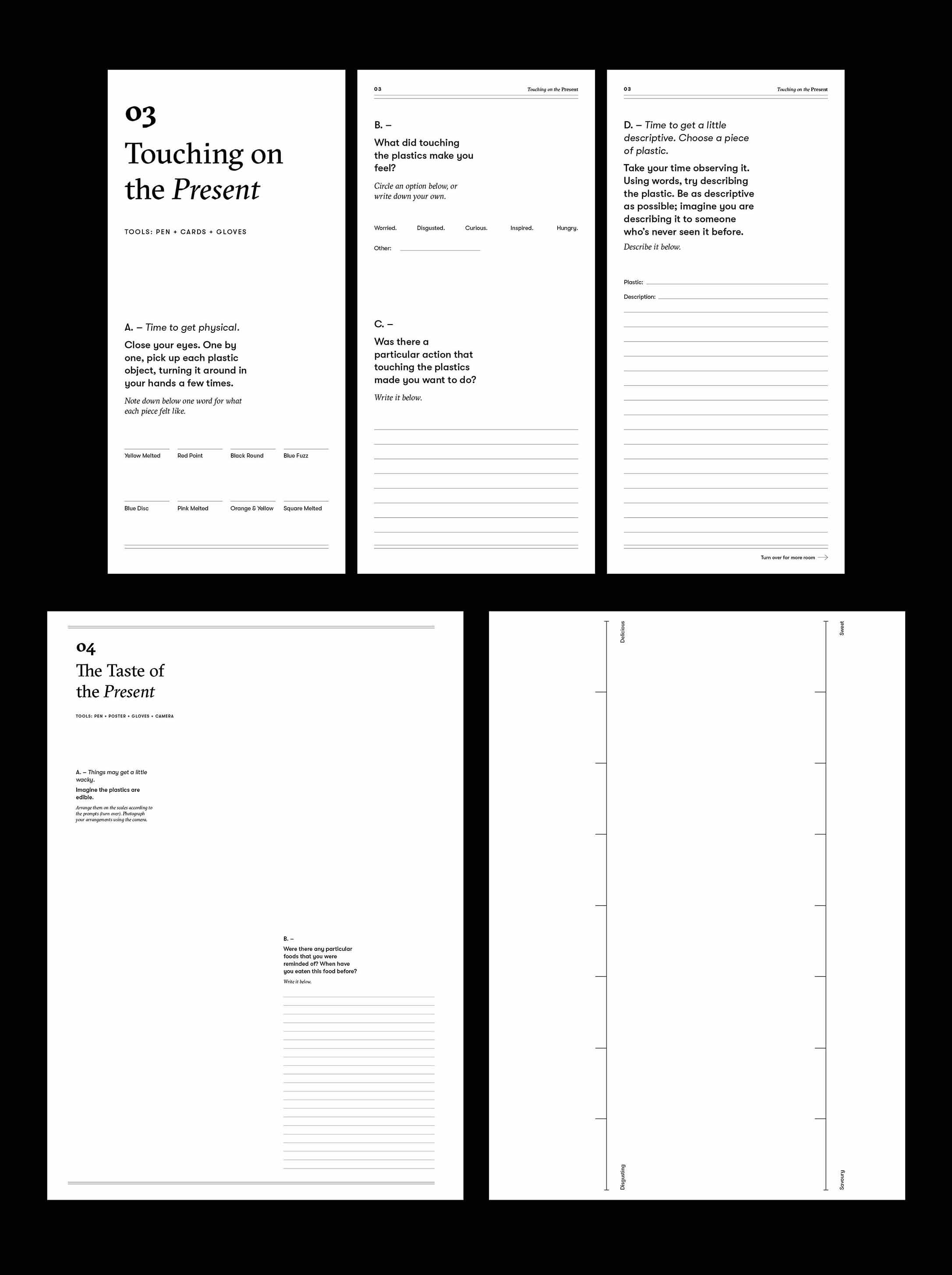

Methods

Most prompts from the previous experiment were discarded except for the photography and creative writing activities, which were re-worded into a creative brief participants could follow loosely (Figure 50 & 51). In setting these probes, I did not want to be too restrictive or force a particular reading of the plastics, so I kept the instructions very open and included a third probe which allowed participants to creatively explore the plastics in whatever way they desired (Figure 51).

Reflection

What was missing from these probes was how changes in thinking and the internal reflections of participants might be recorded to validate the design of this probe. The nature of the activities of the probe were also perhaps a bit too broad, and did not necessarily inspire participants to think ecologically about plastics. I had lost my original intention in this experiment by trying to emulate the playful tone of How to be an Explorer of the World (Smith, 2008).

Insights

The form of the cultural probe needed reconsideration as it was not entirely suitable for the type of information I wanted to gain from participants. The experiences that participants were encouraged to have and the stories they were encouraged to tell also needed reworking. They needed to more clearly stimulate explorations of the longevity of plastic and the way it exists through deep and nonhuman time. I hypothesised that these probe experiments could be translated into participatory design workshops to better suit the nature of interaction I wanted from participants.

Experiment

Stories from the Afterlife Trial Workshop

“Well if it’s in landfill in 10 years’ time, how’s it going to get out of landfill? What do they do? Do they just stay there?”

“Sometimes I’ll have these thoughts, even when I’m throwing garbage out in a plastic bag, but then I sort of erase it from my mind. But I guess when we’re sitting here talking about it … ”

— Participant statements from Trial Workshop #1Aim

To trial a participatory design workshop as a method for generating stories of time with and in consumers (as participants). This workshop design uses interaction-based activities, requiring participants to engage with the materiality of the plastic to form stories about their past and future lives. It aims to facilitate a process of exploration and story generation amongst participants. This seeks to shift participant perspectives to consider the wider and nonhuman timelines that plastic operates at, and to visualise the longevity of plastic waste.

To test the effectiveness of this workshop design, two trial workshops were conducted. These are referred to as Trial Workshop #1 and Trial Workshop #2.

To test the effectiveness of this workshop design, two trial workshops were conducted. These are referred to as Trial Workshop #1 and Trial Workshop #2.

Precedents

This experiment addresses concerns from Experiment: Creative probe that relying on participants to move themselves through the tasks and document their own progress is risky as it depends on the individual motivations of each participant. Using Norris, Karana and Nimkulrat’s ‘Conversing WITH Materials’ (2018) and the Wertheims’ Crochet Coral Reef (2015) as a precedent, it proposes instead the situated context of a participatory design workshop as a solution.

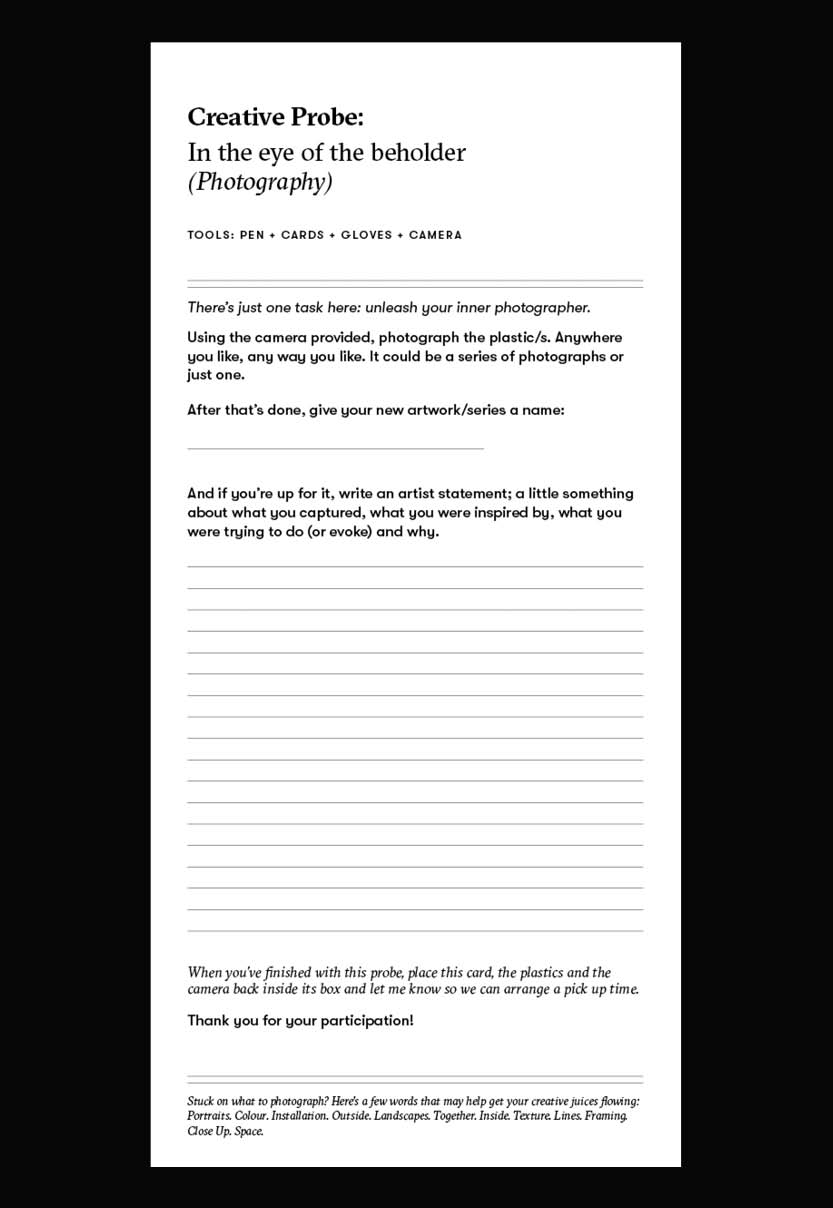

![FIGURE 54 Elements taken from previous experiments.]() It uses the form of participatory design workshops to test the hypothesis generated in the conclusion of Approach Three—that it is the exploratory process of generating stories about plastic which can powerfully impact on understandings of the disposable nature of plastic. The design of this workshop translates the thinking brought out by previous experiments into the form of its activities and prompts (Figure 54). It takes from Approach One: Photographic Stories activities of visual observation of the plastic to shift participants outside of consumer perceptions of plastic waste. It takes from Approach Three: Speculative Stories acts of speculation about the past and future lives of plastic, which introduce nonhuman worldviews to participants as a way of accessing realisations of the nonhuman timelines that plastic operates in. In doing so, it also tests whether the specific processes I have created in these experiments are effective in facilitating conversation about the longevity of plastic in participants, and whether this changes their relationship to plastic in any way.

It uses the form of participatory design workshops to test the hypothesis generated in the conclusion of Approach Three—that it is the exploratory process of generating stories about plastic which can powerfully impact on understandings of the disposable nature of plastic. The design of this workshop translates the thinking brought out by previous experiments into the form of its activities and prompts (Figure 54). It takes from Approach One: Photographic Stories activities of visual observation of the plastic to shift participants outside of consumer perceptions of plastic waste. It takes from Approach Three: Speculative Stories acts of speculation about the past and future lives of plastic, which introduce nonhuman worldviews to participants as a way of accessing realisations of the nonhuman timelines that plastic operates in. In doing so, it also tests whether the specific processes I have created in these experiments are effective in facilitating conversation about the longevity of plastic in participants, and whether this changes their relationship to plastic in any way.

Workshop prompts

The structure of this workshop was made up of the facilitation of prompts to participants within the workshop (Figure 55), and a reflective follow-up survey 2 weeks after their participation.

These prompts intended to encourage participants to discuss and think through two key concepts; the longevity of plastic (through explorations of the past lives and warping of the plastic), and realisations of the deep and nonhuman timescales of plastic (through future speculations of time).

Participants

Participants for these trial workshops were recruited using personal networks. Trial Workshop #1 involved two participants from the fields of mathematics (a professional) and medical science (a student). I was particularly interested in recruiting these participants as their disciplinary backgrounds were so different from my own perspective as a designer. I was curious to see whether they would be open to a more creative and conceptual approach to changemaking outside of empirical methods, or whether they would be sceptical. Entering this workshop, then, there was a pre-conceived hypothesis that the content and design of the workshop would be more effective for certain types of participants than for others. The deciding factor for this would most likely be disciplinary training, or how their worldviews have been constructed.

Trial Workshop #2 had five participants present; from visual communication (professionals), megatronic engineering (a student), freshwater ecology (a student) and interior architecture (a professional). To begin to widen the participant pool to those outside of my own relationship circles, I had encouraged friends to invite their own friends and partners to participate in this workshop, resulting in a mix of participants who I had a pre-existing relationship with and those who I was meeting for the first time in a workshop setting. This resulted in a deliberate mix of empirical and creative mindsets amongst the participants, and I wanted to observe whether these pairings of participants would affect the outcomes and events of the workshop.

Given the larger numbers of Trial Workshop #2, participants were divided into two groups—Group #1 had three participants and Group #2 had two.

The choice of recruiting close friends as participants did, of course, pose limitations and potential bias in the results as they may have unintentionally swayed their responses in order to meet my expectations. However, a comfortable and supportive test environment was needed for practise and this outweighed the limitations.

Trial Workshop #2 had five participants present; from visual communication (professionals), megatronic engineering (a student), freshwater ecology (a student) and interior architecture (a professional). To begin to widen the participant pool to those outside of my own relationship circles, I had encouraged friends to invite their own friends and partners to participate in this workshop, resulting in a mix of participants who I had a pre-existing relationship with and those who I was meeting for the first time in a workshop setting. This resulted in a deliberate mix of empirical and creative mindsets amongst the participants, and I wanted to observe whether these pairings of participants would affect the outcomes and events of the workshop.

Given the larger numbers of Trial Workshop #2, participants were divided into two groups—Group #1 had three participants and Group #2 had two.

The choice of recruiting close friends as participants did, of course, pose limitations and potential bias in the results as they may have unintentionally swayed their responses in order to meet my expectations. However, a comfortable and supportive test environment was needed for practise and this outweighed the limitations.

Methods

This workshop used methods of storytelling to constructing stories about time and custodianship, and had a collaborative workshop structure. Brainstorming was used in its prompt design to facilitate shifts in thought toward the nonhuman longevity of plastic in participants.

Storytelling

Drawing off Stoknes’ arguments that “the more we tell these stories, the more we will begin to live with them” (2015, p. 135), storytelling was used as a key method to facilitate concerns around plastic into the realities and ways of being of participants. In particular, it considered Colebrook’s question—“how might we read or perceive other timelines, other points of view and other rhythms?” (2013, p. 60)—in the intention behind its design.

This was enacted through the design of the workshop itself, which used activities to prompt participants to create stories through the perspective of plastic, as opposed to exploring participant perceptions of plastic. This was mostly achieved through anthropomorphic and analogous storytelling prompts, which asked participants to adopt the experiences of the warped plastics. In doing so, story generation de-centred and shifted “the eye from the body” (Colebrook, 2013, p. 55), creating a reality which recognised and was more ecologically aware of what lies outside of human-centred mindsets.

Explorations of time

Story generation prompts around the past and future deep time of plastic served to further de-centre human realities and encourage speculation about the wider effects of our consumption. This served to bring to light participants’ own mortality compared to that of the nonhuman and plastic, and make them recognise the other timelines in existence in this nonhuman world. This builds on Colebrook’s writings, which state that speculation involves “ranging beyond the present at the cost of its own life” (2013, p. 54).

Custodianship

Participants were asked to choose one plastic out of the 98 on display. This act of choosing had two purposes; to encourage exploration of all the plastics on display and to provide an opportunity for connections to form between participants and the plastic. Participants were given hypothetical custodianship of their chosen plastic and asked in later prompts to do with the plastic what they wished. Crafting the future of their chosen plastic through lenses of custodianship generated dialogue about the longevity of plastic and the wider effects of personal disposal actions.

Collaboration and conversation

The structure of the workshops was collaborative in nature and grouped participants together. This was done both for the comfort of participants and to facilitate discussion amongst participants themselves—thereby exposing participants to differing ideas and perspectives so that they can learn or be challenged by their partners. Similar to ‘Conversing WITH Materials’ (Norris et al., 2018) and Crochet Coral Reef (Wertheim & Wertheim, 2015), conversation was used to encourage a receptiveness and learning in participants.

This workshop assumed that each participant would interpret both the plastic and the workshop prompts in different ways. These served as ‘boundary objects’ (Star & Griesemer, 1989), where the desired outcome was not an enforcement of my own understandings of reality, but a merging or collaboration of the participants’ different perspectives in a way that encouraged further thought and potential motivation in participants. As such, it almost did not matter what the results of these workshops were, only that they sparked a conversation.

Brainstorming activities

Much like the way the experiments in this research were a brainstorm on how to approach the plastics, brainstorming activities—rapid idea generation in the form of mind mapping—were used in this workshop to encourage participants to consider an array of ideas and ways of looking at plastics outside of how they normally would. This was enacted to discourage the development of one single concrete response which may not have challenged participants to see outside human realities. Prompts which asked participants to brainstorm a ‘most likely’ and ‘most ridiculous’ scenario also worked to achieve this. Combined, these sought to “create a safe forum for the expression and free association of creative ideas, and quell any inhibitions of the participants by providing a judgement-free zone to explore new concepts” (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p. 22). This would generate a level of comfort for the participants, and in turn increase receptiveness and involvement in the workshops.

Storytelling

Drawing off Stoknes’ arguments that “the more we tell these stories, the more we will begin to live with them” (2015, p. 135), storytelling was used as a key method to facilitate concerns around plastic into the realities and ways of being of participants. In particular, it considered Colebrook’s question—“how might we read or perceive other timelines, other points of view and other rhythms?” (2013, p. 60)—in the intention behind its design.

This was enacted through the design of the workshop itself, which used activities to prompt participants to create stories through the perspective of plastic, as opposed to exploring participant perceptions of plastic. This was mostly achieved through anthropomorphic and analogous storytelling prompts, which asked participants to adopt the experiences of the warped plastics. In doing so, story generation de-centred and shifted “the eye from the body” (Colebrook, 2013, p. 55), creating a reality which recognised and was more ecologically aware of what lies outside of human-centred mindsets.

Explorations of time

Story generation prompts around the past and future deep time of plastic served to further de-centre human realities and encourage speculation about the wider effects of our consumption. This served to bring to light participants’ own mortality compared to that of the nonhuman and plastic, and make them recognise the other timelines in existence in this nonhuman world. This builds on Colebrook’s writings, which state that speculation involves “ranging beyond the present at the cost of its own life” (2013, p. 54).

Custodianship

Participants were asked to choose one plastic out of the 98 on display. This act of choosing had two purposes; to encourage exploration of all the plastics on display and to provide an opportunity for connections to form between participants and the plastic. Participants were given hypothetical custodianship of their chosen plastic and asked in later prompts to do with the plastic what they wished. Crafting the future of their chosen plastic through lenses of custodianship generated dialogue about the longevity of plastic and the wider effects of personal disposal actions.

Collaboration and conversation

The structure of the workshops was collaborative in nature and grouped participants together. This was done both for the comfort of participants and to facilitate discussion amongst participants themselves—thereby exposing participants to differing ideas and perspectives so that they can learn or be challenged by their partners. Similar to ‘Conversing WITH Materials’ (Norris et al., 2018) and Crochet Coral Reef (Wertheim & Wertheim, 2015), conversation was used to encourage a receptiveness and learning in participants.

This workshop assumed that each participant would interpret both the plastic and the workshop prompts in different ways. These served as ‘boundary objects’ (Star & Griesemer, 1989), where the desired outcome was not an enforcement of my own understandings of reality, but a merging or collaboration of the participants’ different perspectives in a way that encouraged further thought and potential motivation in participants. As such, it almost did not matter what the results of these workshops were, only that they sparked a conversation.

Brainstorming activities

Much like the way the experiments in this research were a brainstorm on how to approach the plastics, brainstorming activities—rapid idea generation in the form of mind mapping—were used in this workshop to encourage participants to consider an array of ideas and ways of looking at plastics outside of how they normally would. This was enacted to discourage the development of one single concrete response which may not have challenged participants to see outside human realities. Prompts which asked participants to brainstorm a ‘most likely’ and ‘most ridiculous’ scenario also worked to achieve this. Combined, these sought to “create a safe forum for the expression and free association of creative ideas, and quell any inhibitions of the participants by providing a judgement-free zone to explore new concepts” (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p. 22). This would generate a level of comfort for the participants, and in turn increase receptiveness and involvement in the workshops.

Data collection methods

To document the events of the workshop, and to gain insight into their effectiveness, the following forms of data were collected:

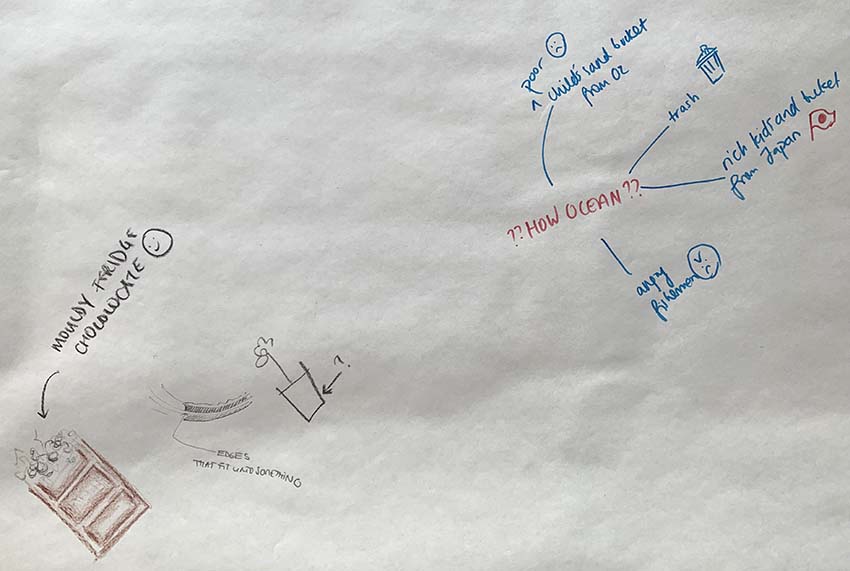

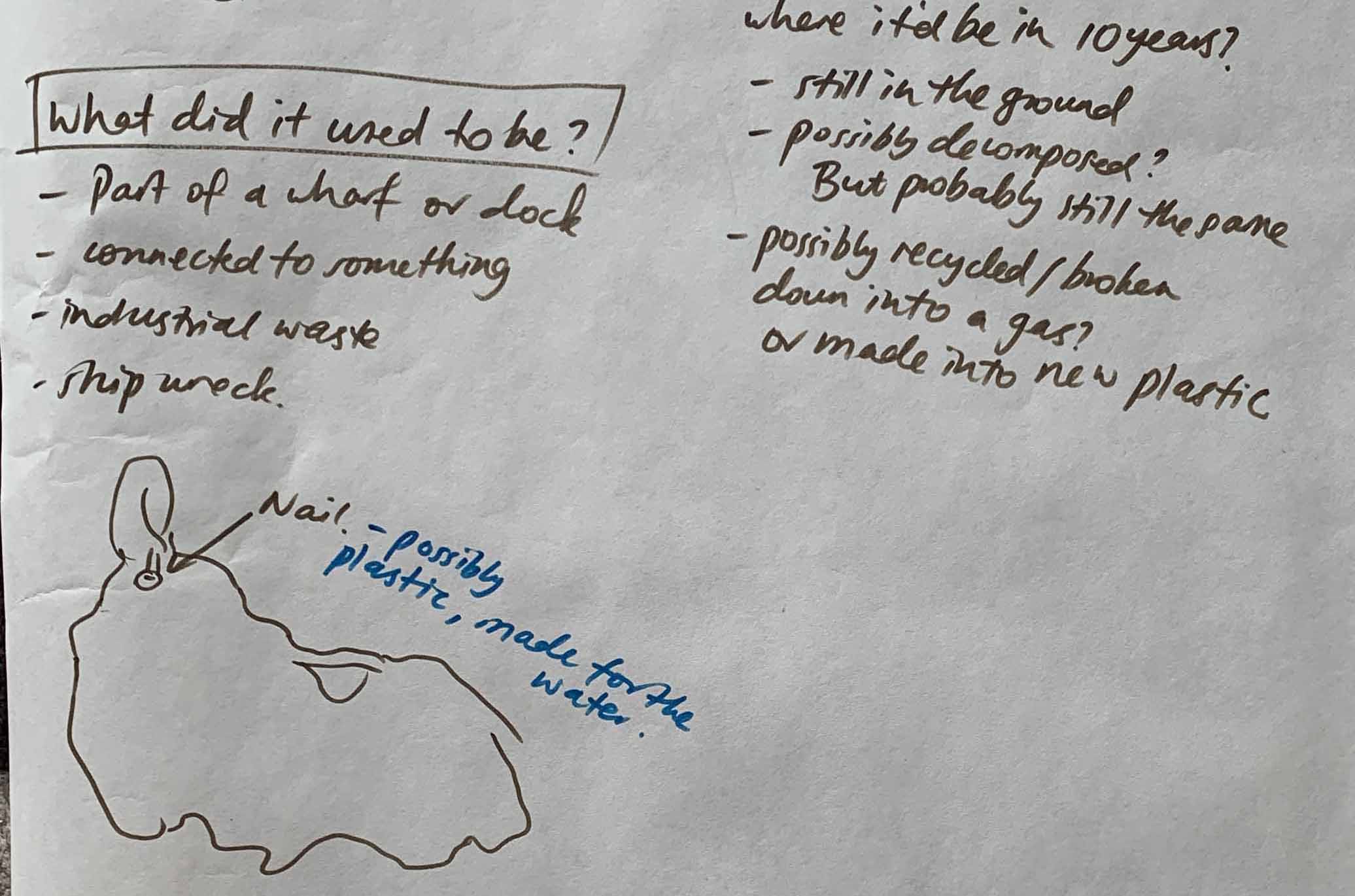

![FIGURE 57 Participant brainstorms from Trial Workshop #1.]()

![FIGURE 58 Participant brainstorms from Trial Workshop #2 Group #1.]()

![FIGURE 59 Participant brainstorms from Trial Workshop #2 Group #2.]()

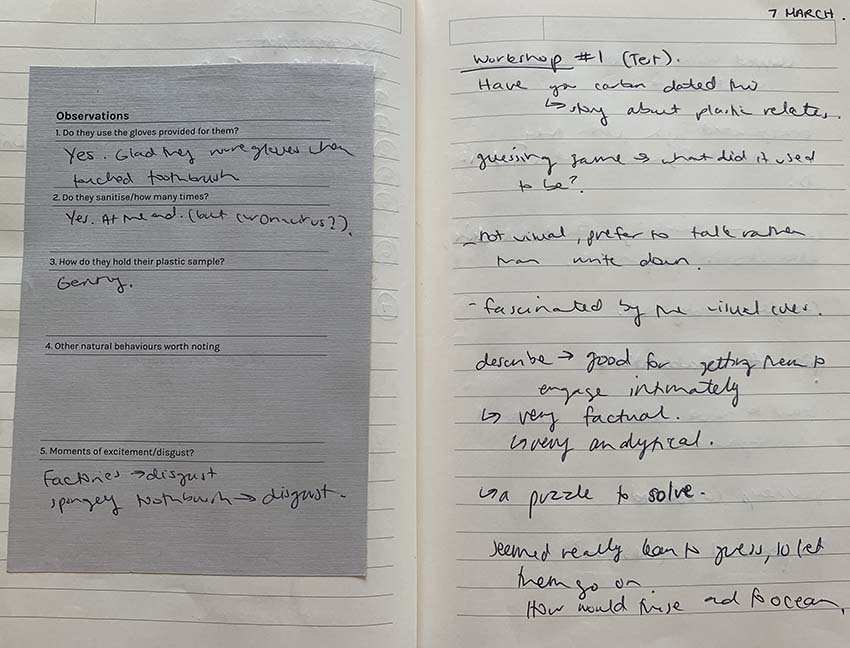

![FIGURE 60 Participant observation notes from Trial Workshop #1.]()

![FIGURE 61 Participant observation notes from Trial Workshop #1.]()

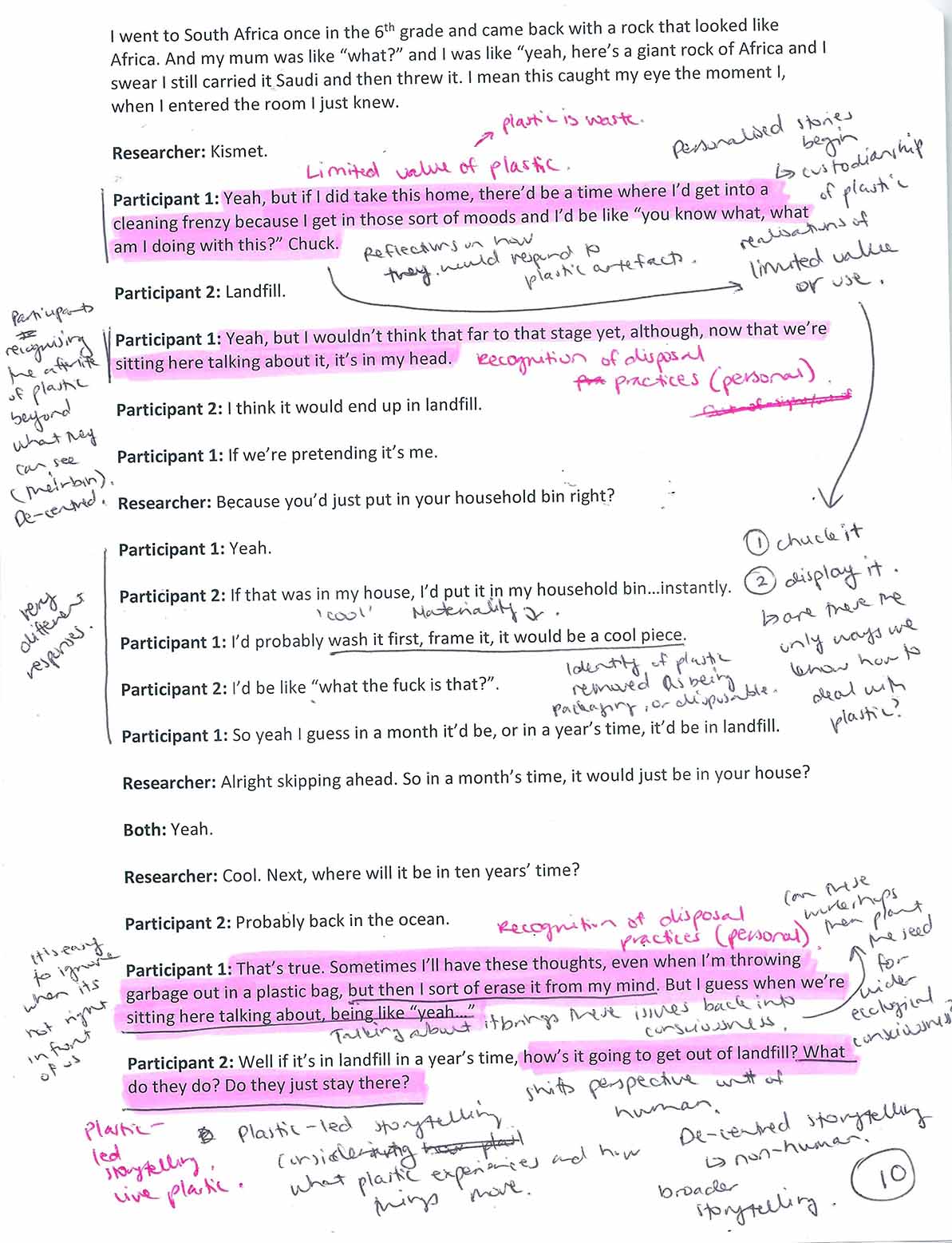

![FIGURE 62 Textual analysis of workshop transcript.]()

- Collaborative participant brainstorms from each participant group; Trial Workshop #1 and Groups #1 and #2 from Trial Workshop #2. These were the mind maps conducted on butcher’s paper (Figures 57-59).

- Observational notes of participant behaviours. I took these while the participants worked to document any behaviours of note. The particular behaviours I was observing were pre-determined before the workshop (Figure 60 & 61).

- Audio recordings of workshop proceedings. Each group was audio recorded, and these were transcribed after the workshop (Figure 62).

- Follow-up survey responses

Methods of analysis

In order to gain insight from the data collected, reflective journaling—or Schön’s practice of reflection-on-action (1983)—was once again conducted. This involved reflecting upon and interpreting the observatory notes, the audio recordings of the workshops (transcribed into text) and the responses to the follow-up surveys. This method of reflective analysis was informed by a content analysis of the data, and—given the heavily text-based forms of the data collected—by a textual analysis of the collected material (Figure 84).

Results

Trial Workshop #1

Participants were particularly drawn to the idea of figuring out what exactly their plastic was, and how it came to be in the form that they saw it in. While this certainly did generate conversation and interest amongst participants, the later storytelling prompts were what brought out nonhuman and ecological discussion amongst participants.

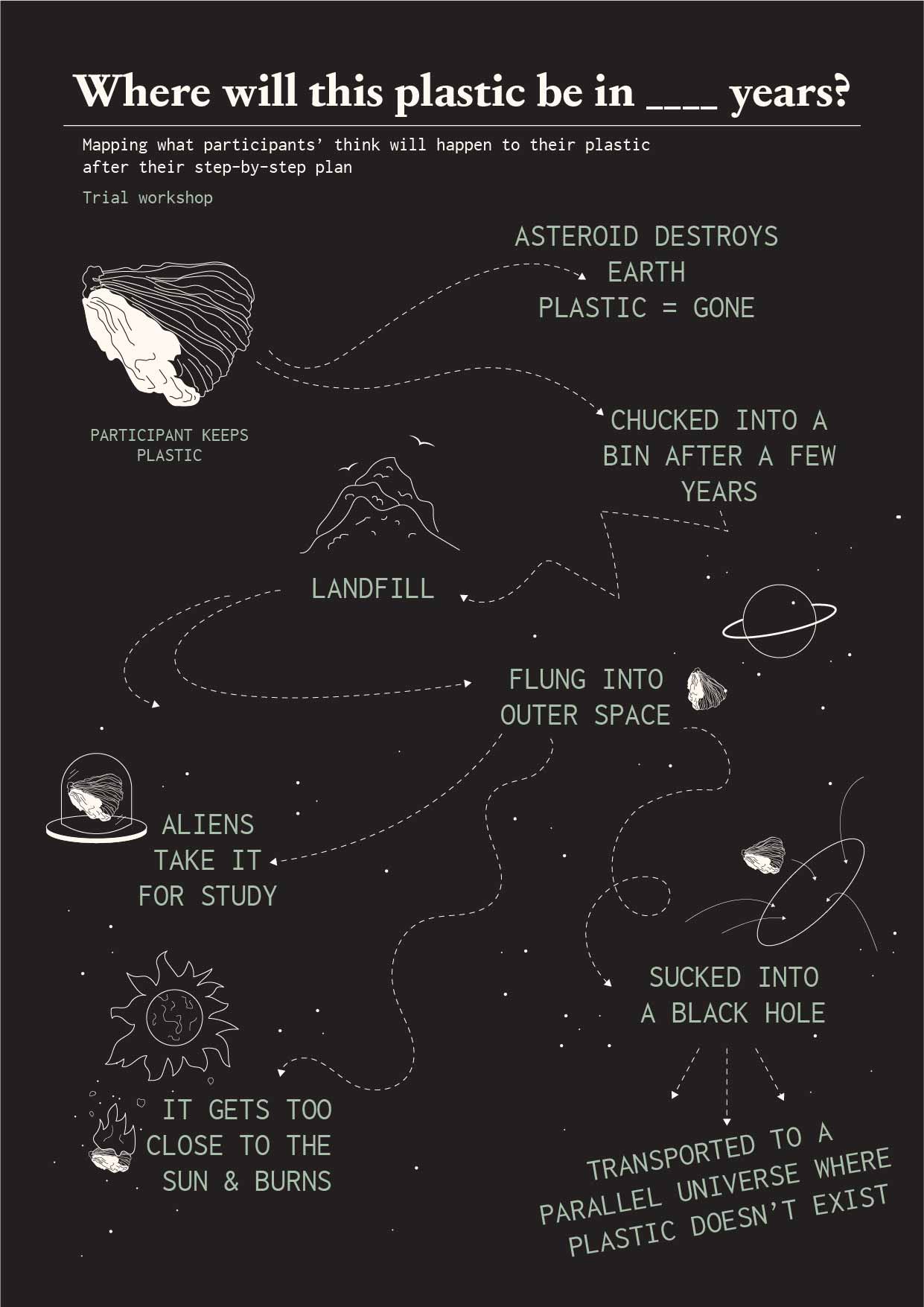

![FIGURE 63 Visualisation of future stories generated by Trial Workshop #1 participants.]() Figure 63 demonstrates how it was storytelling at the 10-year mark that began to shift participants from human-centred worldviews to seeing from the perspective of their plastic artefact. This came about as a result of their unpacking of how exactly their plastic might move between spaces in time:

Figure 63 demonstrates how it was storytelling at the 10-year mark that began to shift participants from human-centred worldviews to seeing from the perspective of their plastic artefact. This came about as a result of their unpacking of how exactly their plastic might move between spaces in time:

“Well if it’s in landfill in 10 years’ time, how’s it going to get out of landfill? What do they do? Do they just stay there?”

— Participant statement

Participants thus began to generate stories through the ‘perspective’ of their specific plastic. Their stories shifted to consider how plastic behaves/exists/persists once in landfill. Effectively de-centred as humans, this ultimately led to the sad realisation that plastic would continue to be present in landfill:

“So if it’s in landfill, it would still be in landfill….”

“Sadly, yeah.”

— Participant statements

Their decision to ultimately dispose of their plastic if given custodianship of it brought forth ecological reflections in participants, with one participant’s remark that it would be “chucked into landfill” being met with:

“Yeah, but I wouldn’t think that far to that stage yet, although, now that we’re sitting here talking about it, it’s in my head.”

“Sometimes I’ll have these thoughts, even when I’m throwing garbage out in a plastic bag, but then I sort of erase it from my mind. But I guess when we’re sitting here talking about it, being like ‘yeah….’” — Participant statements

These reflections demonstrate how thoughts about where waste goes after it is thrown into household bins are often difficult to think about. These responses suggest an inadvertently subconscious regard of household bins as the last place waste goes before it goes ‘away’. It takes more effort on the part of the participant to not only bring these thoughts to the forefront, but to want to bring them to the forefront. The context of this workshop and the nature of the discussions therefore provided a space for this participant to reflect on and recognise their disposal practices.

The collaborative nature of the discussion—particularly the responses of participants to each other’s comments—also illustrated how the situated context of the workshop facilitated ideas and thoughts through conversation. The fact that it was one participant’s comments which drove ecological realisations in another supports this.

Trial Workshop #2

While the preliminary prompts of observation and description facilitated exploration and engagement with the plastics, it was once again the later prompts which proved effective in shifting participants of Trial Workshop #2 towards nonhuman thought.

![FIGURE 64 Visualisation of the future speculations of participants from Trial Workshop #2.]() Group #1’s responses were largely human-centred, even as prompts of time progressed to periods outside of their own lifespans (Figure 64). While their responses took on more fictional scenarios at 100 years to include futures where their plastic was in outer space, the participant who suggested these futures was clearly still operating within human-centred worldviews, stating that:

Group #1’s responses were largely human-centred, even as prompts of time progressed to periods outside of their own lifespans (Figure 64). While their responses took on more fictional scenarios at 100 years to include futures where their plastic was in outer space, the participant who suggested these futures was clearly still operating within human-centred worldviews, stating that:

“I’ll put it in a projector and I don’t know, just launch it out into space, get some other aliens to deal with it.”

— Participant statement

This demonstrated an absence of human de-centring as they still considered themselves to be the main factor influencing where their plastic would be in the future—despite the time period being 100 years in the future, and therefore a point in time where the participant may not be alive. While this perspective was expanded upon to move from an individual perspective to a more general perspective of humanity 1,000 years in the future, the majority of the responses at this point still considered humans as the main contributing actors to their plastic’s future.

Group #2, in comparison, began to shift to nonhuman perspectives after the 1-year mark, in considering how nonhuman actants such as tree roots may interact with their plastic and transform it (Figure 64). They continued to shift between human-centred and wider nonhuman perspectives, with scenarios such as—"we could venture to a volcano and just chuck it in there” being more human-centred—and other scenarios considering how plastic transforms when reacting to nonhuman elements such as heat and water being of a more nonhuman ontology. The results of this workshop therefore demonstrated a mix of nonhuman and human-centred considerations in the participants.

Similar to Trial Workshop #1, all participants in this workshop also chose to discard their plastic after a short period of time:

“Well, I don’t think there’d be much we could do with this.” — Participant statement

“This is not recognisable as plastic anymore. Like it wouldn’t be recycled.” — — Participant statement

This further reiterates how little value plastic had in the minds of participants, particularly when plastic was perceived as an ambiguous material (due to the warping) rather than as a functional object. This did, however, lead participants to acknowledge the problems of disposing—in that there was no alternative other than to dispose—through statements that it was “wishful thinking” otherwise, and that the reality of landfill was “sad”.

Present during this workshop was also an exasperation at the continual persistence of plastic. This exasperation was directed towards being confronted by these realities without an easy and disposable solution. This was demonstrated through participant statements of:

“We don’t need to do anything with it, and not feel guilty about it. Let nature do its thing.”

It was also evidenced in the collectively groaned “oh no” when the prompt asking participants to discuss the 100-year future of their plastic was given. The reluctance and dread towards this question revealed how difficult it was to consider and want to consider beyond the immediacy of human daily life. This highlights how difficult it is to look outside the human, as it relies on “ranging beyond the present at the cost of its own life” (Colebrook, 2013, p. 54). It is no wonder that considering the next 100 years prompted unpleasant reactions in participants, as it began to de-centre them too far from their human realities and called their own mortalities into consciousness.

Participants were particularly drawn to the idea of figuring out what exactly their plastic was, and how it came to be in the form that they saw it in. While this certainly did generate conversation and interest amongst participants, the later storytelling prompts were what brought out nonhuman and ecological discussion amongst participants.

“Well if it’s in landfill in 10 years’ time, how’s it going to get out of landfill? What do they do? Do they just stay there?”

— Participant statement

Participants thus began to generate stories through the ‘perspective’ of their specific plastic. Their stories shifted to consider how plastic behaves/exists/persists once in landfill. Effectively de-centred as humans, this ultimately led to the sad realisation that plastic would continue to be present in landfill:

“So if it’s in landfill, it would still be in landfill….”

“Sadly, yeah.”

— Participant statements

Their decision to ultimately dispose of their plastic if given custodianship of it brought forth ecological reflections in participants, with one participant’s remark that it would be “chucked into landfill” being met with:

“Yeah, but I wouldn’t think that far to that stage yet, although, now that we’re sitting here talking about it, it’s in my head.”

“Sometimes I’ll have these thoughts, even when I’m throwing garbage out in a plastic bag, but then I sort of erase it from my mind. But I guess when we’re sitting here talking about it, being like ‘yeah….’” — Participant statements

These reflections demonstrate how thoughts about where waste goes after it is thrown into household bins are often difficult to think about. These responses suggest an inadvertently subconscious regard of household bins as the last place waste goes before it goes ‘away’. It takes more effort on the part of the participant to not only bring these thoughts to the forefront, but to want to bring them to the forefront. The context of this workshop and the nature of the discussions therefore provided a space for this participant to reflect on and recognise their disposal practices.

The collaborative nature of the discussion—particularly the responses of participants to each other’s comments—also illustrated how the situated context of the workshop facilitated ideas and thoughts through conversation. The fact that it was one participant’s comments which drove ecological realisations in another supports this.

Trial Workshop #2

While the preliminary prompts of observation and description facilitated exploration and engagement with the plastics, it was once again the later prompts which proved effective in shifting participants of Trial Workshop #2 towards nonhuman thought.

“I’ll put it in a projector and I don’t know, just launch it out into space, get some other aliens to deal with it.”

— Participant statement

This demonstrated an absence of human de-centring as they still considered themselves to be the main factor influencing where their plastic would be in the future—despite the time period being 100 years in the future, and therefore a point in time where the participant may not be alive. While this perspective was expanded upon to move from an individual perspective to a more general perspective of humanity 1,000 years in the future, the majority of the responses at this point still considered humans as the main contributing actors to their plastic’s future.

Group #2, in comparison, began to shift to nonhuman perspectives after the 1-year mark, in considering how nonhuman actants such as tree roots may interact with their plastic and transform it (Figure 64). They continued to shift between human-centred and wider nonhuman perspectives, with scenarios such as—"we could venture to a volcano and just chuck it in there” being more human-centred—and other scenarios considering how plastic transforms when reacting to nonhuman elements such as heat and water being of a more nonhuman ontology. The results of this workshop therefore demonstrated a mix of nonhuman and human-centred considerations in the participants.

Similar to Trial Workshop #1, all participants in this workshop also chose to discard their plastic after a short period of time:

“Well, I don’t think there’d be much we could do with this.” — Participant statement

“This is not recognisable as plastic anymore. Like it wouldn’t be recycled.” — — Participant statement

This further reiterates how little value plastic had in the minds of participants, particularly when plastic was perceived as an ambiguous material (due to the warping) rather than as a functional object. This did, however, lead participants to acknowledge the problems of disposing—in that there was no alternative other than to dispose—through statements that it was “wishful thinking” otherwise, and that the reality of landfill was “sad”.

Present during this workshop was also an exasperation at the continual persistence of plastic. This exasperation was directed towards being confronted by these realities without an easy and disposable solution. This was demonstrated through participant statements of:

“We don’t need to do anything with it, and not feel guilty about it. Let nature do its thing.”

It was also evidenced in the collectively groaned “oh no” when the prompt asking participants to discuss the 100-year future of their plastic was given. The reluctance and dread towards this question revealed how difficult it was to consider and want to consider beyond the immediacy of human daily life. This highlights how difficult it is to look outside the human, as it relies on “ranging beyond the present at the cost of its own life” (Colebrook, 2013, p. 54). It is no wonder that considering the next 100 years prompted unpleasant reactions in participants, as it began to de-centre them too far from their human realities and called their own mortalities into consciousness.

Follow-up

survey

responses

survey

responses

The answers to the follow-up surveys highlight two distinct responses in participants (Figure 65). In half of the responses, participants stated that thinking about the future timeline of their plastic was what impacted them the most from the workshop. They wrote that thinking about deep time futures—and the persisting nature of their plastic within these futures—led to new perspectives, and signified a de-centring of them as humans. The other half of the responses stated that thinking through the past lives and journeys of their plastic was what impacted participants and made them consider the longevity of plastic. This highlights the success of storytelling and lenses of time in visualising the longevity of plastic for participants.

These responses also revealed that participants experienced changes in the way they thought about plastic as a result of the workshop. Some participants developed stronger ecological consideration for the products they purchased in everyday life—and consideration of alternatives—while other participants expressed that they began to think about the afterlife and longevity of plastic waste more often. It was thus thinking about nonhuman scales of time—either deep future time, or past lives—that triggered deeper reflections about the impacts of plastic in participants and how they used plastic in their personal lives. This demonstrates two different overall results of the workshops; an increased motivation to act in participants, and an increased motivation to think.

While the results from this survey highlight that thinking about the longevity of plastic motivated ecological thought/action in participants, it is likely that those who responded to this survey were the ones who were affected by the workshop, and who viewed its processes positively.

Reflection

There was an expectation that participants would use the butcher’s paper provided to plan their responses. I realised in hindsight that this is a designerly way of working and was not a natural process for participants from other disciplines. These participants preferred instead to discuss verbally rather than write down their responses. I did find, however, that having the butcher’s paper present made them stick to the prompts and not meander in conversation. As such, providing a medium for participants to record their thoughts and responses will be kept in the workshop design.

These participants did end up embracing the workshop, and I found that having them working together in groups assisted their responses. If one participant was more talkative than another, this also helped the quieter participant become more engaged and active within the workshop. The collaborative storytelling design of this workshop is hence effective. This collaborative structure also helped to facilitate conversation between participants, and allowed them to articulate their own concerns and thoughts about plastic disposal.

Prompt 6 (Figure 55), however, posed a problem in its wording—it was too specific in terms of referring to myself as the actor in the situation and confused participants. This needed to be reframed.

Overall, the responses to the follow-up survey demonstrate this experiment’s success in using stories of time to facilitate ecological thought. The familiarity between myself and the participants, and the security that this brought, however, is a factor to consider in terms of the eagerness of participants in the workshops. More workshops will need to be conducted to expand outside of my immediate circles, and confirm whether this workshop design can be repeated across more varied participant demographics.

These participants did end up embracing the workshop, and I found that having them working together in groups assisted their responses. If one participant was more talkative than another, this also helped the quieter participant become more engaged and active within the workshop. The collaborative storytelling design of this workshop is hence effective. This collaborative structure also helped to facilitate conversation between participants, and allowed them to articulate their own concerns and thoughts about plastic disposal.

Prompt 6 (Figure 55), however, posed a problem in its wording—it was too specific in terms of referring to myself as the actor in the situation and confused participants. This needed to be reframed.

Overall, the responses to the follow-up survey demonstrate this experiment’s success in using stories of time to facilitate ecological thought. The familiarity between myself and the participants, and the security that this brought, however, is a factor to consider in terms of the eagerness of participants in the workshops. More workshops will need to be conducted to expand outside of my immediate circles, and confirm whether this workshop design can be repeated across more varied participant demographics.

Insights

The results from this experiment highlights that this workshop design is effective in meeting its aims; participants successfully engaged in processes of story generation about the past and future lives of plastic, and this did at times facilitate consideration of the wider nonhuman timelines that plastic operates at. These workshops also visualised the longevity of plastic waste for some participants and generated ecological conversation. These workshops will hence continue to be used as the finalisation of this research, with minor revisions based on the feedback mentioned above.

The stories generated by participants also differed greatly to my own stories. This serves as a reminder that participants brought their own understandings of plastic and time to the workshops, and that the processes of storytelling used can create a wide array of explorations and stories. The prompts of the workshop thus encouraged a storytelling relationship between myself and participants, and the stories formed were the results of a collaboration and mutual learning between our different perspectives.

The stories generated by participants also differed greatly to my own stories. This serves as a reminder that participants brought their own understandings of plastic and time to the workshops, and that the processes of storytelling used can create a wide array of explorations and stories. The prompts of the workshop thus encouraged a storytelling relationship between myself and participants, and the stories formed were the results of a collaboration and mutual learning between our different perspectives.

Experiment

What Now? Trial Workshop

“It never ends. Until plastic is completely abolished, it’ll never end.”

— Trial Workshop participant statementAim

A second workshop was designed alongside Stories from the Afterlife. Named What Now?, this workshop was less of a direct translation of earlier experiments, and more of a provocation in response to these processes.

This workshop situates participants in an alternate reality which intervenes with and challenges their normative ones by questioning what humans would do if plastic could not be discarded. It uses prompts that bestows custodianship onto participants throughout time to make the problem of plastic tangible and personal for each participant.

One Trial Workshop was conducted in this experiment to test its design.

This workshop situates participants in an alternate reality which intervenes with and challenges their normative ones by questioning what humans would do if plastic could not be discarded. It uses prompts that bestows custodianship onto participants throughout time to make the problem of plastic tangible and personal for each participant.

One Trial Workshop was conducted in this experiment to test its design.

Precedents

This workshop design was derived from feedback asking me to consider what happens to these warped plastics after this research project, and after they have been ‘saved’ from their usual fates and put on display. It also sought to explore the reflections raised in Approach Three, which considered what would happen to these plastics after this research. Questions such as these proved personally impactful in shifting my perceptions towards the multi-generational and deep time span of plastic, and as such, they were incorporated into the overall intention and design of this workshop.

Workshop prompts

The structure of this workshop also facilitated prompts to participants (Figure 66), but was more conversational and informal in relying on them to drive and guide the conversation.

The same reflective follow-up survey as Experiment: Stories from the Afterlife Trial Workshop was sent to participants two weeks after their participation.

Participants

Participants were once again recruited from personal networks. Three designers (professionals) were chosen as participants to test the more informal structure of this workshop design. I chose designers as I thought they would be more open to the abstract and conceptual nature of the workshop, and would provide a comfortable space to test this more informal design. These designers had a pre-existing relationship with me (and with each other). All three participants were grouped into one group and were encouraged to answer the prompts collaboratively.

Methods

The methods this workshop used are the same as Experiment: Stories from the Afterlife Trial Workshop—storytelling, constructing stories about time, custodianship, a collaborative workshop structure and brainstorming.

Data collection methods

Data was also collected in the same manner as Experiment: Stories from the Afterlife Trial Workshop. Participant brainstorms (Figure 67), participant observation notes (Figure 68), audio recordings and follow-up survey responses were collected.

![FIGURE 67 Trial Workshop participant brainstorms.]()

![FIGURE 68 Trial Workshop participant observation notes.]()

Methods of analysis

I used the same methods as Experiment: Stories from the Afterlife Trial Workshop: reflective journaling, content analyses and visualising information to analyse the results of the collected data and to derive insight.

Results

The more informal and conversational structure of this workshop design allowed participants to segue frequently into anecdotes about how they used plastic in their daily lives. They particularly discussed buying recycled plastic clothing, using KeepCups, takeaway containers and gladwrap. The situated context of the workshop thus prompted self-reflection in participants about their own plastic consumption habits.

![FIGURE 69 Visualisation of Trial Workshop participants’ plan to re-use their plastic.]() When asked to imagine taking custodianship of plastic, participants responded with the idea to use their waste plastic as the basis of an awareness campaign—one that would be used to generate ecological thought in general consumers (Figure 69). They took an environmental education approach in order to:

When asked to imagine taking custodianship of plastic, participants responded with the idea to use their waste plastic as the basis of an awareness campaign—one that would be used to generate ecological thought in general consumers (Figure 69). They took an environmental education approach in order to:

“Subvert the whole story of plastic as waste.”

— Participant statement

These responses highlight a pre-existing ecological awareness in the participants and demonstrates that the workshop provided a space for their ecological views to be voiced collaboratively and affirmed.

![FIGURE 70 Visualisation of Trial Workshop participants’ speculations on what happens to their plastic after their plans for re-use.]() When asked what would happen to their plastic after their campaign ended, one participant responded with:

When asked what would happen to their plastic after their campaign ended, one participant responded with:

“It never ends. Until plastic is completely abolished, it’ll never end.” — Participant statement

Encouraging participants to think past their ideated solutions to see the afterlife of their plastic was initially difficult. This highlighted how challenging it is to shift from immediate human worldviews to more nonhuman and plastic-led ones.

It was a turn to time-based prompts about the future of their specific plastic, however, that began to facilitate a shift to nonhuman thought (Figure 70). This was evidenced when one participant hypothesised that their plastic will be in outer space after 80 years. This statement facilitated a shift in participants to plastic-led perspectives, and allowed them to consider how their plastic might exist in outer space:

“But in outer space wouldn’t it decompose or something? Do you think it would explode?”

— Participant statement

Specifically, it was this shift to more fictional and imaginative contexts of outer space that allowed participants to move from real-world perspectives and instead begin to adopt both plastic-led and nonhuman frames of mind.

When prompts of ‘what now?’ continued to be asked after each new idea, however, one participant exhibited exasperation and remarked:

“You’re giving me an existential crisis.”

— Participant statement

“Subvert the whole story of plastic as waste.”

— Participant statement

These responses highlight a pre-existing ecological awareness in the participants and demonstrates that the workshop provided a space for their ecological views to be voiced collaboratively and affirmed.

“It never ends. Until plastic is completely abolished, it’ll never end.” — Participant statement

Encouraging participants to think past their ideated solutions to see the afterlife of their plastic was initially difficult. This highlighted how challenging it is to shift from immediate human worldviews to more nonhuman and plastic-led ones.

It was a turn to time-based prompts about the future of their specific plastic, however, that began to facilitate a shift to nonhuman thought (Figure 70). This was evidenced when one participant hypothesised that their plastic will be in outer space after 80 years. This statement facilitated a shift in participants to plastic-led perspectives, and allowed them to consider how their plastic might exist in outer space:

“But in outer space wouldn’t it decompose or something? Do you think it would explode?”

— Participant statement

Specifically, it was this shift to more fictional and imaginative contexts of outer space that allowed participants to move from real-world perspectives and instead begin to adopt both plastic-led and nonhuman frames of mind.

When prompts of ‘what now?’ continued to be asked after each new idea, however, one participant exhibited exasperation and remarked:

“You’re giving me an existential crisis.”

— Participant statement

Follow-up

survey

responses

survey

responses

The responses to the second question once again makes evident the ecological concern these workshops can facilitate. While one participant expressed stronger motivation to improve their own ecological practices, the other participant stated that the workshops made them think more—provoking ecological action in one participant and ecological thought in the other. These outcomes highlight that the workshop’s explorations of waste through ideas of custodianship and deep time storytelling can be successful in encouraging participants to reflect ecologically on their personal day-to-day behaviours of disposing and consuming.

Interestingly, one of the responses from a participant signified an increase in ecological thought in general and was not plastic-specific—highlighting that concepts of plastic consumption and sustainability are interrelated and that they can mutually affect one another.

Reflection

The initial responses of participants to the prompts revealed that the framing of the first prompt (Figure 66) was not suitable for the types of responses I wanted. Like the reflections in Experiment: Stories from the Afterlife Trial Workshop, I needed to take myself out of the prompt questions and make them participant focused instead.

I also realised that throughout all the workshops conducted, my participant observations were not as useful as I had hoped. Participants tended to state quite freely what they were thinking; the audio recordings were the more valuable data for identifying participants’ shifts in thought.

The participants’ turn to more fictional scenarios in responding to questions about their plastic’s afterlife—compared to their initial evasion of the topic—suggests that thinking about the future is difficult. Particularly, it was thinking through the future of an inanimate object that was difficult. This aligns with Bennett’s assertions that it is normal to regard objects and waste as “passive” or “inert” (2010, p. vii). Asking participants to consider the future of a seemingly inert object may have therefore prompted more out-of-the-ordinary responses. The participants responding with fiction can thus be interpreted as forming a natural response to a question that was seemingly asking for this kind of response. Despite these more fictional responses, genuine considerations about what would happen to their plastic within these realms was considered and discussed. The creation of fiction hence assisted in facilitating shifts to nonhuman thought.

It was questions of time and persistent time, paired with the introduction of fiction, that led participants to adopt these wider-than-human perspectives. This was particularly evident in one participant’s existential response to continued prompts of ‘what now?’. This response was particularly promising, as it suggested that they began to feel de-centred from a human reality. Stretching their imagination far into the future—and forcing consideration about what continuously happens to their plastic—challenged this participant’s understandings not only of reality, but also of what plastic is and what happens to it after disposal.

I also realised that throughout all the workshops conducted, my participant observations were not as useful as I had hoped. Participants tended to state quite freely what they were thinking; the audio recordings were the more valuable data for identifying participants’ shifts in thought.

The participants’ turn to more fictional scenarios in responding to questions about their plastic’s afterlife—compared to their initial evasion of the topic—suggests that thinking about the future is difficult. Particularly, it was thinking through the future of an inanimate object that was difficult. This aligns with Bennett’s assertions that it is normal to regard objects and waste as “passive” or “inert” (2010, p. vii). Asking participants to consider the future of a seemingly inert object may have therefore prompted more out-of-the-ordinary responses. The participants responding with fiction can thus be interpreted as forming a natural response to a question that was seemingly asking for this kind of response. Despite these more fictional responses, genuine considerations about what would happen to their plastic within these realms was considered and discussed. The creation of fiction hence assisted in facilitating shifts to nonhuman thought.

It was questions of time and persistent time, paired with the introduction of fiction, that led participants to adopt these wider-than-human perspectives. This was particularly evident in one participant’s existential response to continued prompts of ‘what now?’. This response was particularly promising, as it suggested that they began to feel de-centred from a human reality. Stretching their imagination far into the future—and forcing consideration about what continuously happens to their plastic—challenged this participant’s understandings not only of reality, but also of what plastic is and what happens to it after disposal.

Insights

The results of this workshop once again revealed how unexpected and different the stories formed were to my own. This reinforces the idiosyncrasy of each participant’s understanding of plastic waste and affirms that the use of participatory design workshops allows for a way to communicate with participants rather than at participants.

Overall, this workshop proved successful in shifting participants to tangibly recognise the longevity of plastic. As such, this workshop design was also enacted as the finalisation of this research project. Similar to Stories from the Afterlife, participants outside of my own networks needed to be used for these final workshops to confirm that this workshop was effective for those without an established relationship with me.

Overall, this workshop proved successful in shifting participants to tangibly recognise the longevity of plastic. As such, this workshop design was also enacted as the finalisation of this research project. Similar to Stories from the Afterlife, participants outside of my own networks needed to be used for these final workshops to confirm that this workshop was effective for those without an established relationship with me.