Approach Three:

Speculative Stories

This approach uses methods of storytelling to move away from human-centred interpretations of reality. This is facilitated by generating stories that explore how plastic waste persists to exist outside the human (Bennett, 2010; Colebrook, 2013). This approach specifically engages with processes of speculative, time-based and anthropomorphic storytelling to generate these stories about the warped plastics. The outcomes of this approach intended to highlight these realities as a way of making considerations of a wider-than-human world more accessible and common (Stoknes, 2015, p. 135).

Experiment

Dealing with Waste

Aim

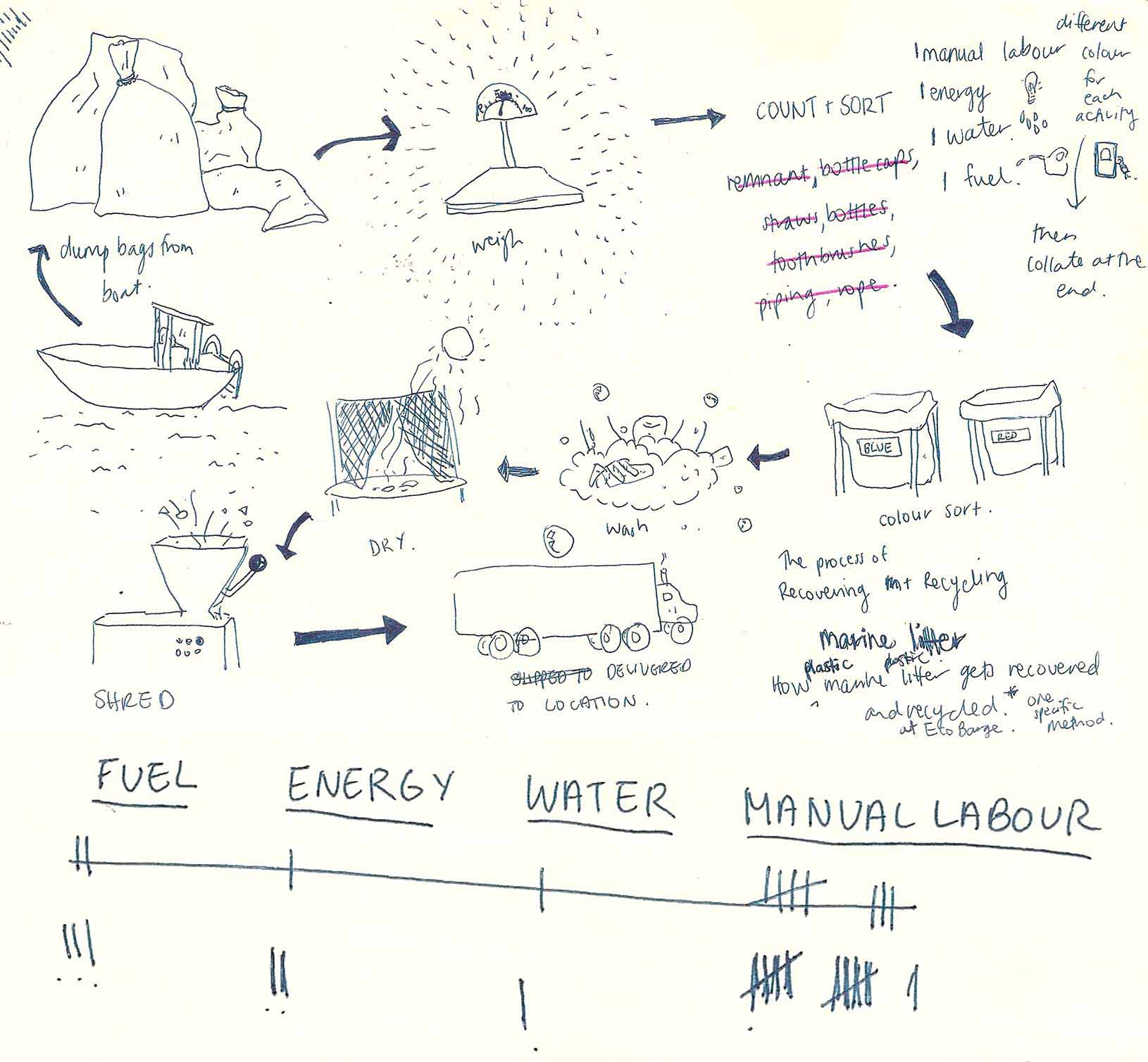

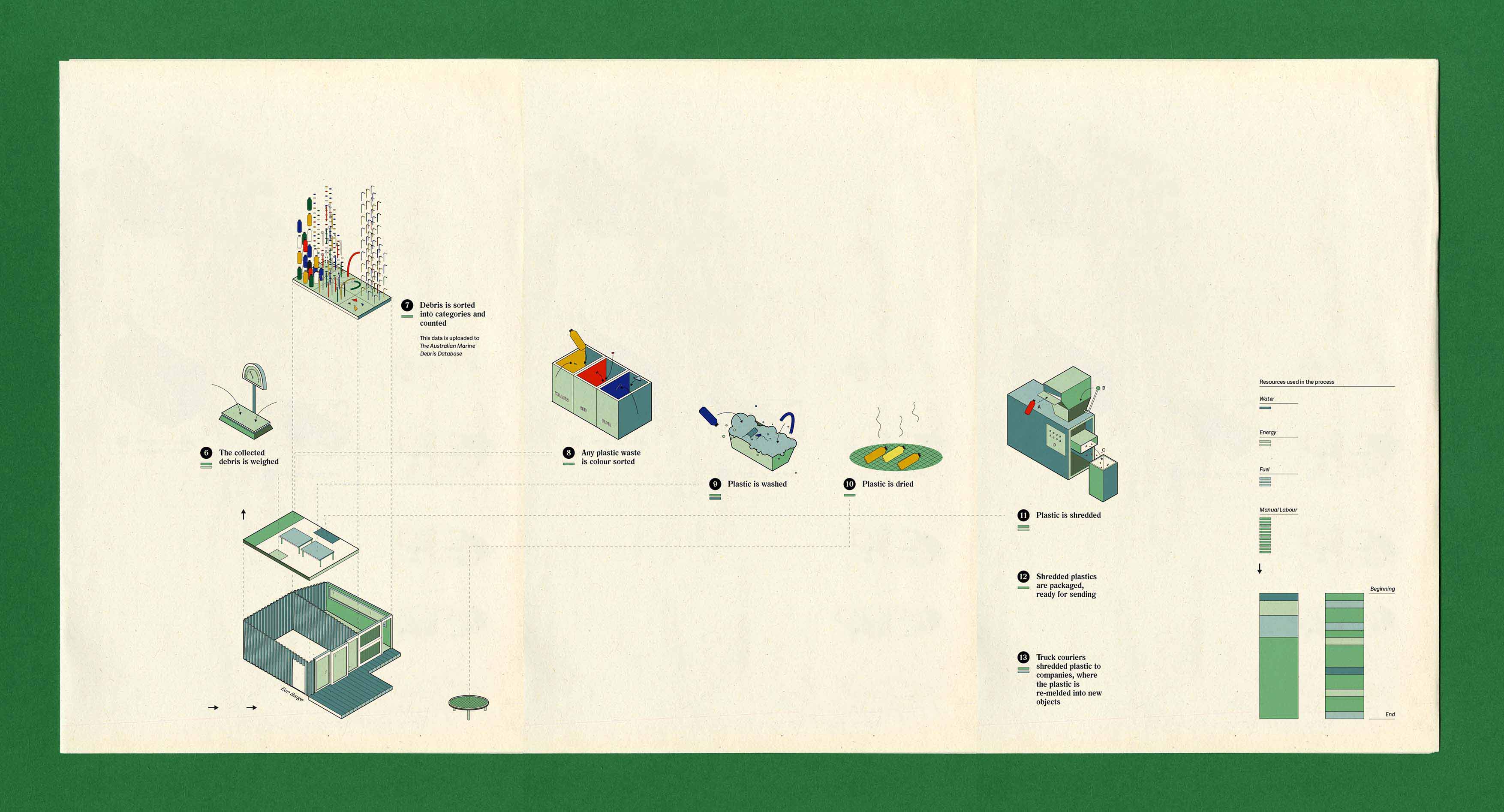

To visualise how plastic still continues to exist even after a ‘solution’ to address them is enacted. This was intended to be achieved through diagramming what Eco Barge does with collected plastics, which is to prepare them for recycling—an extremely laborious and resource dependant process. This also sought to demonstrate that recycling is not as simple or easy as what it is often represented as (or as sustainable), and to make known that one of our solutions to plastic is not really a solution at all.

Methods

Reflection

Diagramming in this more factual manner reduced the story of what happens to plastic after collection to processes and steps—to facts that could inform consumers, but wouldn’t necessarily motivate, inspire or stimulate them. It became even more evident through this experiment that interpreting these plastics through fact-based lenses was uninteresting.

Insights

This experiment motivated a stronger desire to shift outside of my fact-based interpretation of the plastic—to see the plastic as more than a static waste object. More experiments needed to be undertaken to explore new lenses and how exactly to achieve this.

Experiment

Re/Collected

Aim

This experiment sought to use the assemblages of plastic observed at Eco Barge to subvert the ‘out of sight, out of mind’ mentality with which we dispose of plastic, and consequently promote considerations of the afterlife of plastic. It facilitated wider questioning and critique of how consumers don’t know what to do with their plastic waste, even waste collectors like Eco Barge. Humans do not have the capacity to mentally or technologically process this waste.

Precedents

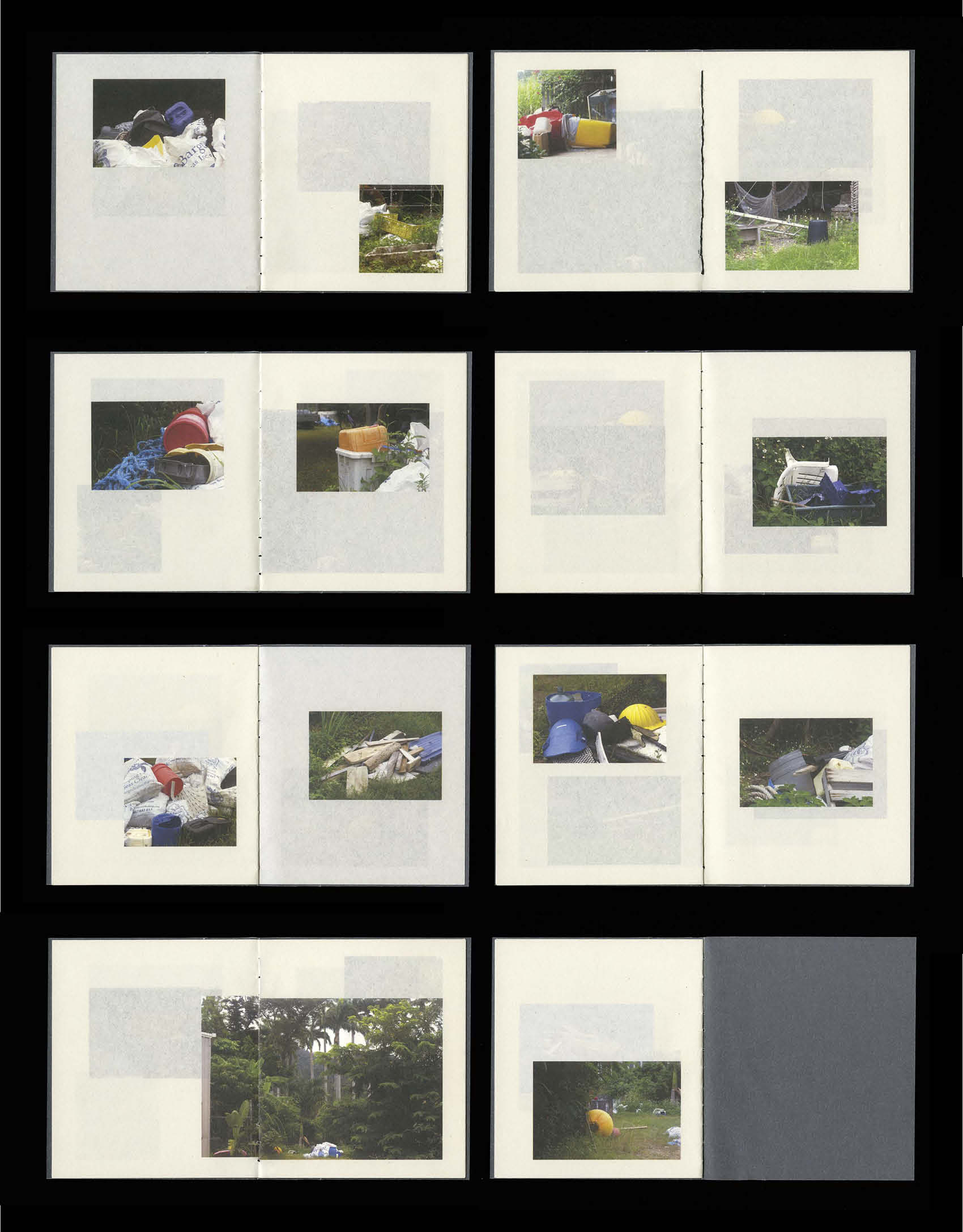

I made these observations while at the Eco Barge site, where I noticed a large amount of assemblages of plastic distributed throughout the space. These plastics were too large and solid to be put through the plastic shredder which would turn them into pellets to be recycled—as explained by Fiona Broadbent, the volunteer coordinator at Eco Barge (personal communication, 21 March, 2019)—and had been tossed aside as a temporary solution, sitting outside amongst the trees and grass. To me, these gatherings of waste silently questioned, ‘what now?’.

This experiment used these assemblages as a method to manifest Bennett’s argument that being conscious of how waste persists after disposal might generate a considered ecological consciousness in consumers (2010, p. 4). It also responds to the reflections in Experiment: Dealing with Waste by exploring the afterlives of plastic outside fact-based lenses. The documentation of these assemblages draws from the in-situ style of photography present in Chris Jordan’s Midway: Message from the Gyre (2009-present).

This experiment used these assemblages as a method to manifest Bennett’s argument that being conscious of how waste persists after disposal might generate a considered ecological consciousness in consumers (2010, p. 4). It also responds to the reflections in Experiment: Dealing with Waste by exploring the afterlives of plastic outside fact-based lenses. The documentation of these assemblages draws from the in-situ style of photography present in Chris Jordan’s Midway: Message from the Gyre (2009-present).

Methods

Adopting a sociologist’s approach, the assemblages were photographed in-situ to provide glimpses of the post-disposal lives of plastic (as opposed to previous experiments, which objectively documented plastic as a phenomena). Framed amongst the greenery of grass and trees, the extremely solid and seemingly permanent material properties of plastic juxtaposed against the natural, more easily decaying environment, and highlighted that it would be impossible for the plastic to break down. From this, a story was formulated about the plastic as being forgotten and enduring ‘forever’ in this condition.

These photographs were organised sequentially into a book format—a form recognisably used to house stories—to highlight that there is a story to these photographs (Figure 30). The use of generous white space in the book’s composition, as well as my decision to include long shots of the plastic in nature, served to generate a feeling of great stillness, and to perpetuate this unsettling notion of plastic persisting forever without end.

These photographs were organised sequentially into a book format—a form recognisably used to house stories—to highlight that there is a story to these photographs (Figure 30). The use of generous white space in the book’s composition, as well as my decision to include long shots of the plastic in nature, served to generate a feeling of great stillness, and to perpetuate this unsettling notion of plastic persisting forever without end.

Reflection

The abandoned assemblages at Eco Barge shifted my point of view to imagine what these plastics were potentially ‘feeling’ in their abandoned state. This de-centred me as a human, as it made me attune to recognising that there are other perspectives in existence besides my own human one—and that plastic waste can be one of these nonhuman perspectives. This realisation anthropomorphised the pieces of plastic, allowing me to recognise their agency and liveliness, and that they are entities that existed with and outside of humans.

The adoption of anthropomorphism as a lens was a powerful way of beginning to create a perception of plastic as more than a disposable consumer by-product. Shifting the point of view used in previous experiments from that of a human (me) talking about plastic, to that of imagining what plastic experiences, inspired a speculative consideration of what happens to plastic as an entity that can experience life after disposal. I found the adoption of this lens particularly successful in its ability to make me question where my own plastic waste is now, and also in its ability to encourage me to consider how I might feel under the same conditions as waste.

These assemblages—and my interpretation of them as anthropomorphic—expanded upon the ideas of time from Experiment: Fossilised Plastic. Thinking of the plastics as abandoned raised questions about whether they would ever be removed, or if they would just continue to persist in that space forever without end. This deeply unsettled me as it highlighted the deep time span that plastics can operate at, and had the effect of making me realise how insignificant my own lifespan is compared to that of plastic. Being conscious of how plastic persists after disposal at a timescale incomprehensible to humans—and in environments away from human eyes—facilitated recognition of the other realities outside of my own; where things do experience life, although differently. This also re-conceptualised understandings of time for me, and made it apparent that time exists outside of and beyond humans. Other entities such as plastic, then, are not constrained within human timescales and continue living and existing regardless of humans. The assemblages of plastic, and the story they presented, thus provided me with the ability to access and understand Colebrook’s ideas of the “other timelines, other points of view and other rhythms” (2013, p. 60) outside the human. This strengthened my sense of ecological responsibility, as it made tangible how the effects of plastic consumption reverberate at a nonhuman scale; a scale where humans cannot control and undo the damage.

This experiment hence also facilitated a new interpretation of Bennett’s theories. My previous understanding of Bennett’s concept of ‘liveliness’ (2010) as referring to materials that can warp, change and adapt evolved though this experiment to include consideration of things as capable of existing and experiencing life through time. This demonstrates how practice can inform and shift conceptual understandings of theory. It also highlights how storytelling around nonhuman (or more-than-human) concepts of time can be used as a method for facilitating ecological concern.

While not a conscious decision at the time of undertaking this experiment, the small size of this publication (approximately 11cm x 13cm) can also be seen as an attempt to establish feelings of ‘cuteness’ in viewers. This borrows from aesthetic theorist Sianne Ngai’s statement that things which are small in size can “evoke tenderness” and paints the subject in need of protection (2012, pp. 3-4). This highlights that my design decision to work in small scales may have been an intention to create empathy and concern for the plastics (not just about plastic). This demonstrates that the material form of these outcomes can be used to influence perceptions and interpretations of the subject. The evaluation of this experiment—formulated in hindsight through reflection—also demonstrates how reflective practice can synthesise the learnings from critical theory, and thereby inform design practice.

The adoption of anthropomorphism as a lens was a powerful way of beginning to create a perception of plastic as more than a disposable consumer by-product. Shifting the point of view used in previous experiments from that of a human (me) talking about plastic, to that of imagining what plastic experiences, inspired a speculative consideration of what happens to plastic as an entity that can experience life after disposal. I found the adoption of this lens particularly successful in its ability to make me question where my own plastic waste is now, and also in its ability to encourage me to consider how I might feel under the same conditions as waste.

These assemblages—and my interpretation of them as anthropomorphic—expanded upon the ideas of time from Experiment: Fossilised Plastic. Thinking of the plastics as abandoned raised questions about whether they would ever be removed, or if they would just continue to persist in that space forever without end. This deeply unsettled me as it highlighted the deep time span that plastics can operate at, and had the effect of making me realise how insignificant my own lifespan is compared to that of plastic. Being conscious of how plastic persists after disposal at a timescale incomprehensible to humans—and in environments away from human eyes—facilitated recognition of the other realities outside of my own; where things do experience life, although differently. This also re-conceptualised understandings of time for me, and made it apparent that time exists outside of and beyond humans. Other entities such as plastic, then, are not constrained within human timescales and continue living and existing regardless of humans. The assemblages of plastic, and the story they presented, thus provided me with the ability to access and understand Colebrook’s ideas of the “other timelines, other points of view and other rhythms” (2013, p. 60) outside the human. This strengthened my sense of ecological responsibility, as it made tangible how the effects of plastic consumption reverberate at a nonhuman scale; a scale where humans cannot control and undo the damage.

This experiment hence also facilitated a new interpretation of Bennett’s theories. My previous understanding of Bennett’s concept of ‘liveliness’ (2010) as referring to materials that can warp, change and adapt evolved though this experiment to include consideration of things as capable of existing and experiencing life through time. This demonstrates how practice can inform and shift conceptual understandings of theory. It also highlights how storytelling around nonhuman (or more-than-human) concepts of time can be used as a method for facilitating ecological concern.

While not a conscious decision at the time of undertaking this experiment, the small size of this publication (approximately 11cm x 13cm) can also be seen as an attempt to establish feelings of ‘cuteness’ in viewers. This borrows from aesthetic theorist Sianne Ngai’s statement that things which are small in size can “evoke tenderness” and paints the subject in need of protection (2012, pp. 3-4). This highlights that my design decision to work in small scales may have been an intention to create empathy and concern for the plastics (not just about plastic). This demonstrates that the material form of these outcomes can be used to influence perceptions and interpretations of the subject. The evaluation of this experiment—formulated in hindsight through reflection—also demonstrates how reflective practice can synthesise the learnings from critical theory, and thereby inform design practice.

Insights

This experiment reveals that recognition and awareness of nonhuman timelines and realities—of consideration of a world wider than humans—can facilitate ecological reflection about my own actions of consumption and disposal. This highlights that shifting consumers to consider the nonhuman is an aim to continue to explore and work towards. It also illuminates that lenses of time are effective in facilitating ecological understandings of the longevity of plastic.

Anthropomorphic speculation about the afterlives and deep time lifespans of plastic provided the ability to access and tangibly recognise these nonhuman worlds. The creation of anthropomorphic, time-based and speculative stories are thus continued as a way of exploring and visualising the nonhuman longevity of plastic.

While this experiment successfully changed my own perspective to consider the nonhuman worlds plastic operates in, this was a result of making and firsthand experience. I questioned whether viewing this experiment would have the same effect on other consumers. More experimentation was needed to explore how to present these stories in ways that would successfully engage consumers.

Anthropomorphic speculation about the afterlives and deep time lifespans of plastic provided the ability to access and tangibly recognise these nonhuman worlds. The creation of anthropomorphic, time-based and speculative stories are thus continued as a way of exploring and visualising the nonhuman longevity of plastic.

While this experiment successfully changed my own perspective to consider the nonhuman worlds plastic operates in, this was a result of making and firsthand experience. I questioned whether viewing this experiment would have the same effect on other consumers. More experimentation was needed to explore how to present these stories in ways that would successfully engage consumers.

Experiment

The toothbrush

Aim

The toothbrush sought to further explore how the anthropomorphic, lively and deep time qualities of plastic could be utilised to draw out reflections about the nonhuman longevity of plastic in consumers. It uses creative storytelling as a method and medium to deploy these concepts.

Precedents

This experiment builds on the imagined afterlife of plastic introduced in Experiment: Re/Collected. It seeks, however, to explore these themes in ways that do not require the theoretical preludes needed in the previous experiment to come to such conclusions.

It draws on the anthropomorphic storytelling of the podcast Everything is Alive (Chillag, 2018-present) as a precedent. Unlike Everything is Alive (Chillag, 2018-present), however, this story is not told in an interview format with direct dialogue, but through descriptive internal dialogue of the plastic’s own thoughts.

It draws on the anthropomorphic storytelling of the podcast Everything is Alive (Chillag, 2018-present) as a precedent. Unlike Everything is Alive (Chillag, 2018-present), however, this story is not told in an interview format with direct dialogue, but through descriptive internal dialogue of the plastic’s own thoughts.

Methods

Reflection

Even though I knew that a toothbrush typically ends up in landfill where it then stays forever, writing about it ended up making this understanding much more tangible. It unsettled me to know that all my past toothbrushes have met similar depressing ends. It had the effect of making me not want to subject those experiences to any object or thing anymore. While this approach is entirely fictional and I myself do not believe that plastics have emotions and thoughts, anthropomorphism shifted my perspective to consider the experiences of this toothbrush after disposal and strengthened a recognition of more alternative nonhuman worldviews.

While I enjoyed using fiction to open up my way of seeing, I did find it incredibly difficult to formulate a complete, logical and working story about the toothbrush (due to the fact that I do not necessarily see myself as a writer). This also shed some insight into my own practice, and how I prefer to construct unresolved and fragmented stories to allow for a more interpretive reading rather than a literal one.

I was also wary of continuing further with this approach as the use of such blatant anthropomorphism was perhaps too gimmicky; would adult consumers be able to fully embrace what is often considered a childish way of thinking, or would they immediately dismiss my work?

While I enjoyed using fiction to open up my way of seeing, I did find it incredibly difficult to formulate a complete, logical and working story about the toothbrush (due to the fact that I do not necessarily see myself as a writer). This also shed some insight into my own practice, and how I prefer to construct unresolved and fragmented stories to allow for a more interpretive reading rather than a literal one.

I was also wary of continuing further with this approach as the use of such blatant anthropomorphism was perhaps too gimmicky; would adult consumers be able to fully embrace what is often considered a childish way of thinking, or would they immediately dismiss my work?

Insights

I realised that it was the act of writing that facilitated my concern for the longevity of plastics. It was generating these anthropomorphic stories through nonhuman lenses that shifted my worldviews to recognise the longevity and post-disposal lives of plastic. I once again questioned whether other consumers reading this story would experience the same revelations. Instead of writing a story for others to read, could an outcome be created that encouraged consumers to formulate their own personal understandings? Ways of anthropomorphising the plastic without overt human comparisons also needed to be experimented further.

Experiment

From here to there

Aim

This experiment aimed to tell a more abstracted and less anthropomorphised story about the life of plastic. It used fragmented storytelling as a way of visualising the journeys of time and use for the warped plastics.

Precedents

It refines on storytelling methods used in Experiment: The toothbrush. Rather than using personas and overt anthropomorphism as lenses, this experiment recorded the journeys of these plastics to bring into awareness the post-disposal spaces plastics are often relegated to.

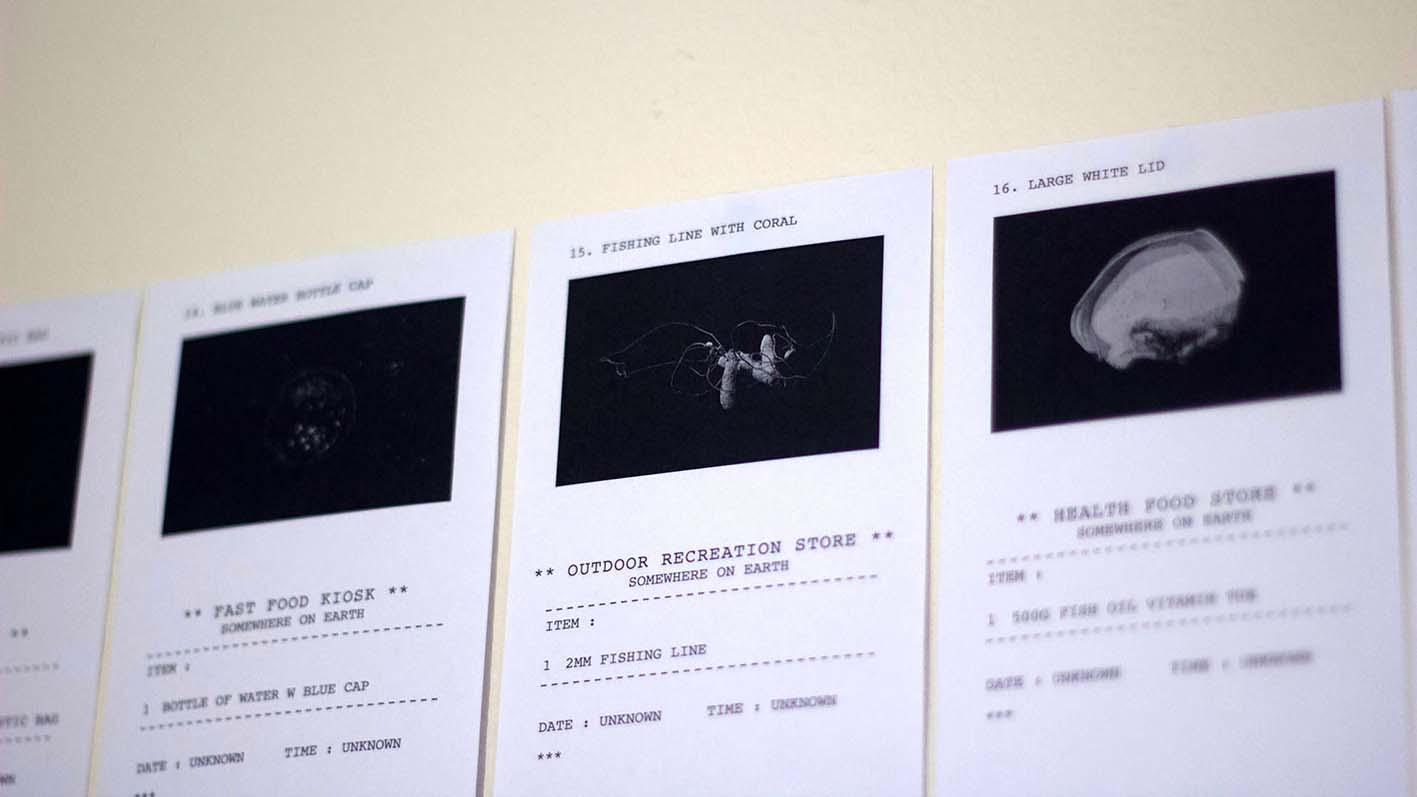

Methods

f how they ended up in the ocean and their journey after humans.

The formula for crafting these journeys considered:

- The type of store they were bought from as a consumer item

- How they were discarded, the circumstances surrounding it and where this happened (e.g. a home or public building)

- How they travelled from their place of disposal to their next location

- How they travelled from that location to the ocean

- Their collection by Eco Barge

- Their collection by me

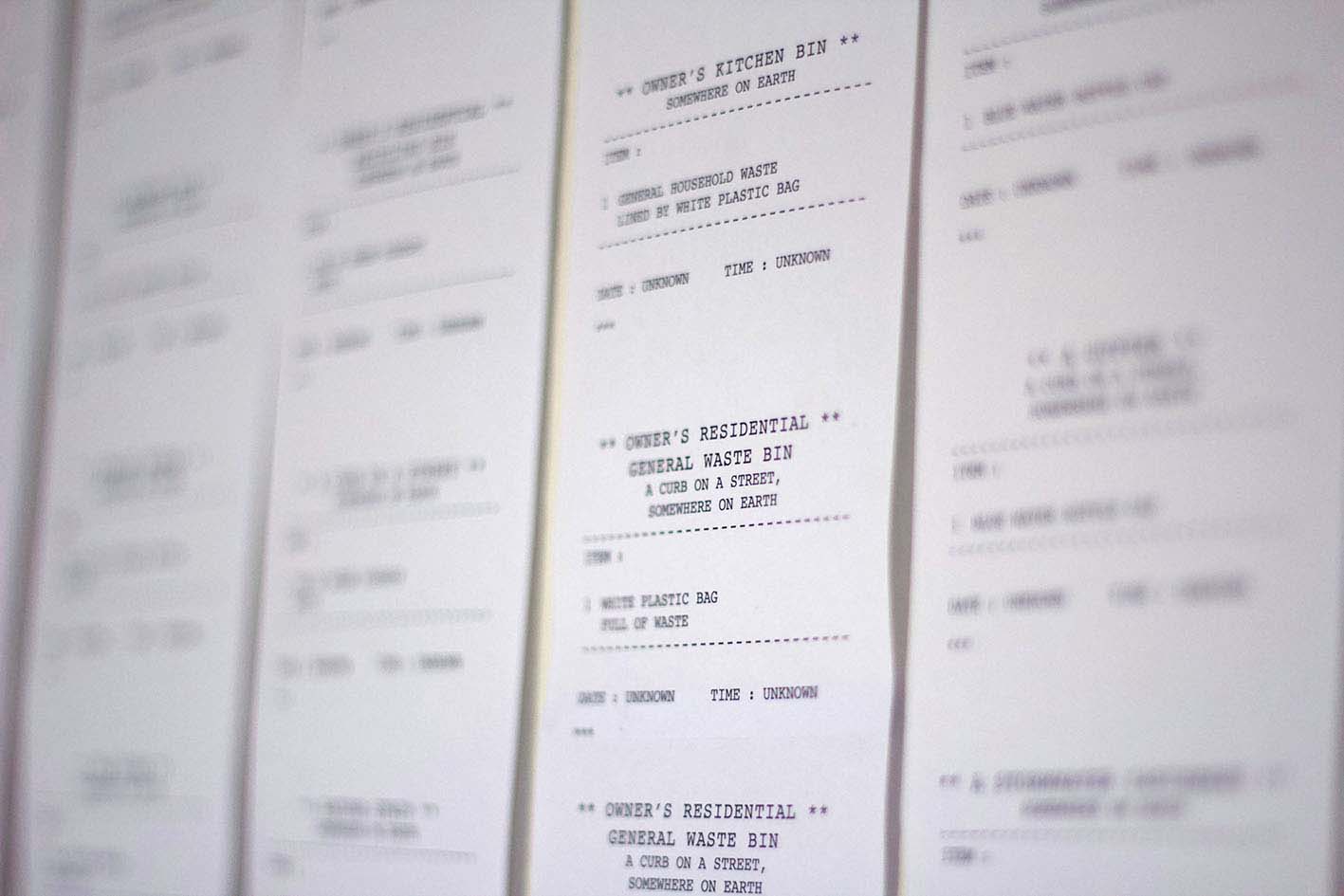

These stories were intentionally left open ended. The question marks after the record of them in my living room ask ‘what next?’ and highlight that the journey for plastic never really ends (Figure 36).

The form of the receipt was chosen to visualise these journeys as they are already artefacts that record the moving of an object from one place to go to another. They document the place that an object comes from (such as a library book, or groceries from a supermarket), but not where they are going, much like these warped plastics. This metaphor of the receipt sought to communicate that all matter is redistributed rather than disintegrating (both physically and chemically).

Reflection

Feedback from supervisors for this experiment cited that the choice of presentation was perhaps too text heavy and uniform, making it uninviting for consumers to engage with in detail. This experiment made a statement about the overall image rather than each individual story.

The act of generating stories which traced the past of these plastics all the way up to my collection of them did, however, prompt consideration of where they might go next after being in my care. Questions about what conditions would make them leave my care also surfaced—it was highly unlikely that I would ever discard of these plastics, so the only reasonable explanation was that they would leave my care after I die. This raised further considerations about what these plastics would be doing in the time between the completion of this research project and my eventual demise, and reiterated an understanding that there is no solution to the dilemma of what to do with our waste; the systems we operate in (such as recycling, collecting from beaches, personal collections and museum collections) only seem to delay the inevitability of plastic ending up in landfill.

The act of generating stories which traced the past of these plastics all the way up to my collection of them did, however, prompt consideration of where they might go next after being in my care. Questions about what conditions would make them leave my care also surfaced—it was highly unlikely that I would ever discard of these plastics, so the only reasonable explanation was that they would leave my care after I die. This raised further considerations about what these plastics would be doing in the time between the completion of this research project and my eventual demise, and reiterated an understanding that there is no solution to the dilemma of what to do with our waste; the systems we operate in (such as recycling, collecting from beaches, personal collections and museum collections) only seem to delay the inevitability of plastic ending up in landfill.

Insights

Understanding that these plastics would only be ‘protected’ during my lifetime led me to attribute a custodianship of the collected plastics to myself. This allowed me to recognise the limitations of collecting these plastics, in that they would persist to exist beyond my lifespan. Giving custodianship of the warped plastics was thus a potential strategy to connect consumers to tangibly recognise and visualise the nonhuman and multi-generational lifespan of plastic, and this is explored further in later experiments.

It was particularly this more fragmented storytelling form that facilitated this visualisation of the longevity of plastic. Considering the future of the plastic in a cause-and-effect and step-by-step journey map helped to slowly build towards considerations of their deep time futures. This is hence also a potential method for providing consumers access to understandings of longevity.

Building on ideas of nonhuman longevity, I also wanted to speculate and unpack further how these specific warped plastics might exist—and where—after my generation is no longer around. Exploring a world where we are no longer alive and present could prove to generate conversation and make concepts of the longevity and persistent existence of plastic waste tangible to consumers.

It was particularly this more fragmented storytelling form that facilitated this visualisation of the longevity of plastic. Considering the future of the plastic in a cause-and-effect and step-by-step journey map helped to slowly build towards considerations of their deep time futures. This is hence also a potential method for providing consumers access to understandings of longevity.

Building on ideas of nonhuman longevity, I also wanted to speculate and unpack further how these specific warped plastics might exist—and where—after my generation is no longer around. Exploring a world where we are no longer alive and present could prove to generate conversation and make concepts of the longevity and persistent existence of plastic waste tangible to consumers.