Final Workshops

This section details the Final Workshops conducted for both Stories from the Afterlife and What Now? workshop designs. They will be distinguished from the Trial Workshops conducted previously by the nomenclature of ‘Final Workshop’.

I use these Final Workshops to prove that generating conversation and stories about the afterlife of plastic can shift the perspectives of participants to consider the nonhuman longevity of plastic waste. Stories from the Afterlife does this through fragmented story generation, which asks participants to incrementally map the future of a warped plastic and build towards considerations of deep time futures. What Now? achieves this by attributing custodianship of a warped plastic to participants, and having them imagine what would happen to the plastic under their care and even after their death.

These Final Workshops particularly sought to test whether:

- The workshop designs—which translate my methods of experimentation and story generation about the warped plastics—are effective in facilitating understandings of the longevity of plastic waste in participants, and leads to ecological reflections

- The workshops are repeatable and can be applied to shift change for a range of consumer participants

- These workshops can demonstrate how the theories of Bennett, Colebrook, Stoknes and Tsing can be communicated and disseminated through participatory design workshops

Participants

Participants for Final Workshops were recruited via an open call-out for Higher Degree Research (HDR) students at UTS. They were recruited across Faculties of Science, Business, Architecture, Arts and Social Science, Law, Engineering and IT. This open invitation method of recruiting participants was conducted to allow for groups of individuals with no pre-existing relationships to come together.

The Institute for Sustainable Futures was excluded from this list to avoid an ecological bias in the results. As individuals already focused on ecological matters, the workshops would either be met highly favourably by them or have little impact on them. The Design Faculties were also excluded to avoid designerly bias—trial workshops already involved a large number of designers, and they displayed a way of viewing the world that was too similar to my own.

Stories from the Afterlife Final Workshop participants

Three participants—from Faculties of Science, Business (with an undergraduate degree in Science) and Architecture—attended this workshop. Of these participants, two of them identified as extremely ecologically minded, and were currently conducting research into sustainable practices within their fields.

What Now? Final Workshop participants

Three participants—from disciplines of science, business and communication—were present in this workshop. Two of these participants also identified as ecologically minded, while the third identified as more aware but not particularly passionate about the issue of plastic. In this instance, none of the participants had pre-existing relationships with each other, although one participant did have a pre-existing relationship to myself.

The Institute for Sustainable Futures was excluded from this list to avoid an ecological bias in the results. As individuals already focused on ecological matters, the workshops would either be met highly favourably by them or have little impact on them. The Design Faculties were also excluded to avoid designerly bias—trial workshops already involved a large number of designers, and they displayed a way of viewing the world that was too similar to my own.

Stories from the Afterlife Final Workshop participants

Three participants—from Faculties of Science, Business (with an undergraduate degree in Science) and Architecture—attended this workshop. Of these participants, two of them identified as extremely ecologically minded, and were currently conducting research into sustainable practices within their fields.

What Now? Final Workshop participants

Three participants—from disciplines of science, business and communication—were present in this workshop. Two of these participants also identified as ecologically minded, while the third identified as more aware but not particularly passionate about the issue of plastic. In this instance, none of the participants had pre-existing relationships with each other, although one participant did have a pre-existing relationship to myself.

Conducting workshops during COVID-19

As Final Workshops took place in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), certain health and safety measures which were not present during the Trial Workshops were enacted. These measures were undertaken in accordance with UTS and Australian Government social distancing and hygiene regulations.

Government restrictions on unnecessary travel to campus also affected the recruitment of participants; some participants cancelled their attendance before the workshop due to COVID-19. It is also possible that the amount of participants volunteering was reduced—as only those who felt comfortable enough to travel volunteered.

Due to COVID-19 interfering with the collection of participant observations (particularly the use of gloves and hand sanitiser), the method of observing participants using a pre-determined list of behaviours was abandoned for the Final Workshops.

Government restrictions on unnecessary travel to campus also affected the recruitment of participants; some participants cancelled their attendance before the workshop due to COVID-19. It is also possible that the amount of participants volunteering was reduced—as only those who felt comfortable enough to travel volunteered.

Due to COVID-19 interfering with the collection of participant observations (particularly the use of gloves and hand sanitiser), the method of observing participants using a pre-determined list of behaviours was abandoned for the Final Workshops.

Methods

See Experiment: Stories from the Afterlife Trial Workshop for a description of the methods used in the design of these workshops, as well as its data collection methods.

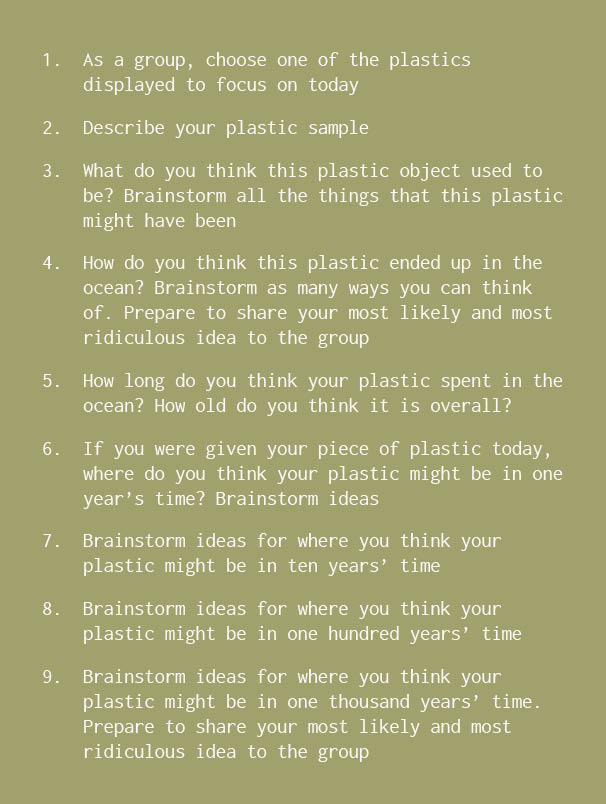

![FIGURE 72 Stories from the Afterlife revised prompts.]()

![FIGURE 73 What Now? revised prompts.]()

Analysis of results

Similar to the Trial Workshops, the results of the Final Workshops were analysed through a content and textual analysis. See Experiment: Stories from the Afterlife Trial Workshop for more details.

Analysing the results of the Trial Workshops proved time consuming and laborious. This was due to the fact that I collected many different forms of data, and did not know going into the Trial Workshops exactly what I was looking for or what the outcomes would be. Conducting and reflecting on these Trial Workshops brought about a clarity of intent that allowed for a set of criteria to be developed. This would assist in evaluating the results of the Final Workshops. This included questions of:

These criteria are used to frame interpretations of the results from the Final Workshops, and are used to determine whether the prompts were successful in meeting their aims.

Analysing the results of the Trial Workshops proved time consuming and laborious. This was due to the fact that I collected many different forms of data, and did not know going into the Trial Workshops exactly what I was looking for or what the outcomes would be. Conducting and reflecting on these Trial Workshops brought about a clarity of intent that allowed for a set of criteria to be developed. This would assist in evaluating the results of the Final Workshops. This included questions of:

- Did interacting with the warped plastics engage participants?

- Did storytelling prompts stimulate concern and awareness of the longevity of plastic?

- Did giving participants custodianship of the plastic lead them to consider the longevity of plastic?

- Did the workshops facilitate ecological thought/concern/responsibility in participants overall?

These criteria are used to frame interpretations of the results from the Final Workshops, and are used to determine whether the prompts were successful in meeting their aims.

Analysis structure

The results of these Final Workshops are presented in the next sections through four parts:

Part One: Participant reactions to the warped plastics ︎︎︎

Part Two: Stories from the Afterlife Final Workshop results ︎︎︎

Part Three: What Now? Final Workshop results ︎︎︎

Part Four: Reflection on workshop findings ︎︎︎

Part One: Participant reactions to the warped plastics ︎︎︎

Part Two: Stories from the Afterlife Final Workshop results ︎︎︎

Part Three: What Now? Final Workshop results ︎︎︎

Part Four: Reflection on workshop findings ︎︎︎

Part One

Participant reactions to the warped plastics

Early prompts in the Stories from the Afterlife workshop asked participants to select, observe and describe one warped plastic. The first prompt in What Now? also asked participants to select and describe one warped plastic. The range of reactions from participants during these activities highlights that the warped materiality of these plastics are affective and do stimulate responses. They also highlight two main ways participants responded to the plastics; through language and through behaviour. This section discusses and analyses these responses in order to draw meaning from them.

The Final Workshops saw a high number of reactions to the plastic from participants. These took on the form of verbal statements, which were documented through the audio recordings of the workshop proceedings. This highlighted that the audio recordings (and their transcripts) could be ‘mined’ or searched for verbal responses as a way of providing tangible evidence of these reactions. Mining the audio recordings of the Trial Workshops also revealed participant reactions that had not been noticed initially. As such, participant reactions from all five workshops conducted (three Trial Workshops, two Final Workshops) are synthesised and presented in this section.

The Final Workshops saw a high number of reactions to the plastic from participants. These took on the form of verbal statements, which were documented through the audio recordings of the workshop proceedings. This highlighted that the audio recordings (and their transcripts) could be ‘mined’ or searched for verbal responses as a way of providing tangible evidence of these reactions. Mining the audio recordings of the Trial Workshops also revealed participant reactions that had not been noticed initially. As such, participant reactions from all five workshops conducted (three Trial Workshops, two Final Workshops) are synthesised and presented in this section.

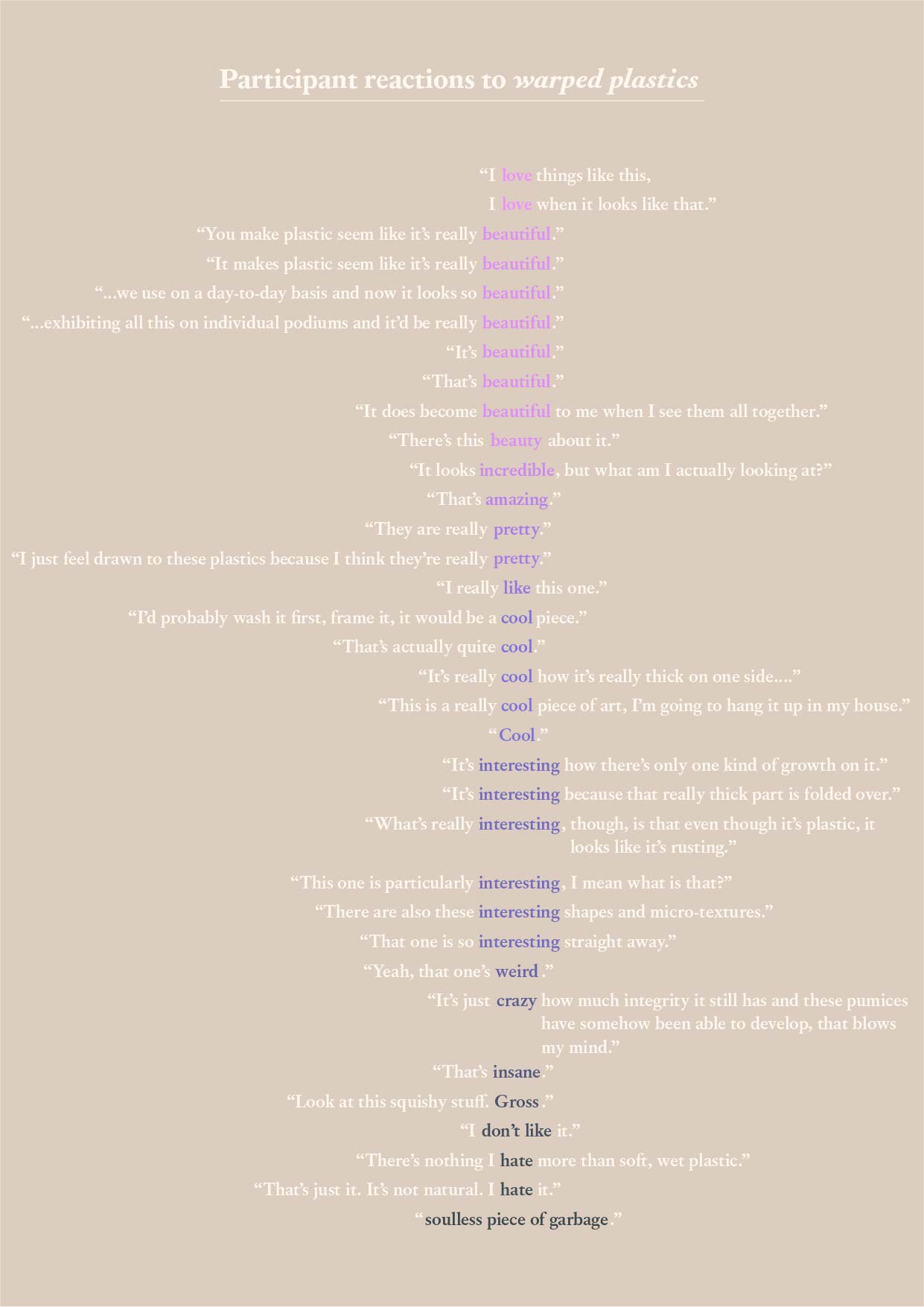

Participant reactions evidenced through language

Mapping participant reactions to the plastic highlighted two insights; there was no general consensus reached in terms of how participants reacted to the plastics, and the reactions of participants ranged from very positive (love) to very negative (hate) (Figure 74).

What also became evident from this mapping was how some reactions were more common across participants. When these reactions were abstracted into colour and shape (Figure 75), reactions of ‘beautiful’, ‘cool’ and ‘interesting’ were revealed to be the most common responses. However, as the nature of this research is qualitative rather than quantitative, little meaning can be deduced from the significance of the quantity of occurrence—rather, what is meaningful is that they occurred at all.

![FIGURE 75 A record of the frequency of each participant reaction.]()

What also became evident from this mapping was how some reactions were more common across participants. When these reactions were abstracted into colour and shape (Figure 75), reactions of ‘beautiful’, ‘cool’ and ‘interesting’ were revealed to be the most common responses. However, as the nature of this research is qualitative rather than quantitative, little meaning can be deduced from the significance of the quantity of occurrence—rather, what is meaningful is that they occurred at all.

Participant reactions evidenced through behaviour

A collation of the participant observation notes also recorded reactions from participants. These can only be described through a written account of the event so as not to lose any ‘data’ or richness of the occurrence, as outlined below:

Disgust

A reaction of disgust was expressed towards the toothbrush by one participant—aimed at the “squishy” materiality of the padding which had started to decay. When they saw this toothbrush, they said they were glad they had donned gloves.

Tactile

Another participant refused the option of wearing gloves, stating: “I want to touch them with my fingers”.

Refusal of gloves

Despite both Stories from the Afterlife and What Now? Final Workshops taking place in the midst of COVID-19—and with various sanitary measures becoming the new normal—many participants asked if it was necessary to wear disposable gloves when touching the plastic. This also occurred during the Trial Workshop of What Now?, where a participant remarked that it was “ironic” and counterintuitive to be given disposable plastic gloves to hold waste plastics. This highlights a pre-existing ecological awareness in some of the participants.

Kismet

Upon reflecting on their choice of plastic items to focus on for the duration of the workshop, one participant stated, “when I entered the room I just knew”, in regards to their choice.

Too beautiful

One participant in particular questioned whether the plastics were too beautiful and whether that would have the opposite effect to making people want to consume less plastic:

“It makes plastic seem like it’s really beautiful. But in the bigger picture, plastics are a really damaging thing for the environment, so it shouldn’t be beautiful?”

— Participant statement

Another participant found it interesting that they perceived the collection of warped plastics in front of them as beautiful, despite often being repulsed by plastic in stores such as Smiggle. When reflecting on why this reaction occurred, they stated a reason was possibly that the plastics had been “buffeted out” by the ocean and thus resembled more natural materials. Another reason given was that while waste plastics are often seen in the singular in natural environments—and therefore feel out of place and disgusting—the warped plastics in front of them were displayed in a collection and thus appeared more intentional.

Disgust

A reaction of disgust was expressed towards the toothbrush by one participant—aimed at the “squishy” materiality of the padding which had started to decay. When they saw this toothbrush, they said they were glad they had donned gloves.

Tactile

Another participant refused the option of wearing gloves, stating: “I want to touch them with my fingers”.

Refusal of gloves

Despite both Stories from the Afterlife and What Now? Final Workshops taking place in the midst of COVID-19—and with various sanitary measures becoming the new normal—many participants asked if it was necessary to wear disposable gloves when touching the plastic. This also occurred during the Trial Workshop of What Now?, where a participant remarked that it was “ironic” and counterintuitive to be given disposable plastic gloves to hold waste plastics. This highlights a pre-existing ecological awareness in some of the participants.

Kismet

Upon reflecting on their choice of plastic items to focus on for the duration of the workshop, one participant stated, “when I entered the room I just knew”, in regards to their choice.

Too beautiful

One participant in particular questioned whether the plastics were too beautiful and whether that would have the opposite effect to making people want to consume less plastic:

“It makes plastic seem like it’s really beautiful. But in the bigger picture, plastics are a really damaging thing for the environment, so it shouldn’t be beautiful?”

— Participant statement

Another participant found it interesting that they perceived the collection of warped plastics in front of them as beautiful, despite often being repulsed by plastic in stores such as Smiggle. When reflecting on why this reaction occurred, they stated a reason was possibly that the plastics had been “buffeted out” by the ocean and thus resembled more natural materials. Another reason given was that while waste plastics are often seen in the singular in natural environments—and therefore feel out of place and disgusting—the warped plastics in front of them were displayed in a collection and thus appeared more intentional.

Insights

These responses to the warped plastics confirm that these artefacts can engage and draw reactions from participants. The mixture of fascination and curiosity in participants highlight that the warped forms of these plastics made them see plastic in ways alternative to its normative representations as packaging, waste or consumer objects. The particular language used by participants made this evident; they described and responded to these plastics as an ambiguous material. I turn here to the writings of philosopher Immanuel Kant (1790/1952), aesthetic theorist Sianne Ngai (2007; 2012) and consumer researchers Caleb Warren and Margaret Campbell (2014) to better understand the implications of the language used by these participants.

Beautiful

The reaction of some participants to regard the plastic as beautiful is a stark contrast to the way plastic and plastic waste is usually perceived in consumer contexts. This highlights that the warping of these plastics shifted the prespectives of participants to regard plastic in new ways, and made them aware of the more material nature of plastic. It also highlights that the workshop itself provided a context removed from consumer mindsets, which allowed for alternative perspectives to emerge. Kant’s statement that a person’s reactions of ‘beautiful’ are made in response to “what simply pleases him” (1790/1952, p. 49) reveals that these participants positively responded to these plastics; they were engaged by the aesthetic and visual qualities of the warped plastics. These particular responses confirm my own considerations of the plastic as beautiful.

The statement of one participant that it was problematic to communicate these plastics as beautiful demonstrates a tension between being captivated by these forms and knowing that this warped plastic should not be admired. This highlights that the visual qualities of these plastics are engaging in ways that might challenge those with pre-existing ecological mindsets, and bring these discussions to the forefront. There seems to be a limit, however, to how much these aesthetic responses can impact others—Kant also describes reactions of ‘beautiful’ as being delight without interest (1790/1952, p. 50). This suggests that reactions of beauty do not facilitate much stimulation outside of the object itself. This supports my conclusion in earlier experiments that purely presenting plastic through aestheticised means cannot directly lead to ecological reflection in consumers.

Cool

Warren and Campbell state that reactions of ‘cool’ emerge “when its behaviors diverge from the norm” (2014, p. 543). The participants may have hence regarded the warped plastics as ‘cool’ because it was unfamiliar and outside the norm. These responses support my hypothesis in this research that warped plastics can be used to challenge normative conventions. These responses also highlight that participants were responding to more than the aesthetic of these warped plastics; they began to engage conceptually with what this plastic represented.

Interesting

Responses of ‘interesting’ also signify a conceptual reaction in participants, and mark a response to the “relatively small surprise of information or variation from an existing norm” (Ngai, 2012, p. 5). The ‘interesting’ is defined by the occurrence of new information and the way this interacts with pre-existing worldviews—“the interesting marks a tension between the unknown and the already known” (Ngai, 2012, p. 5). This definition of interest as a “collision” or “contradiction” (Ngai, 2012, p. 12) illuminates that participants who expressed these reactions were challenged by the plastics in some way through exposure to their existence. This once again confirms that these warped plastics successfully caused shifts in participants. However, Ngai’s statements that these responses are “trivial” (2012, p. 18) suggest that the participants were only slightly impacted by the presence of these plastics. This in turn reveals that being in the presence of these warped plastic artefacts are not enough to powerfully evoke shifts in participants—but are perhaps enough to trigger thought, conversation and reflection.

Disgust

Instances of disgust and hatred in participants can be interpreted through Kant’s theory that disgust is an object “insisting, as it were, upon our enjoying it, while we still set our face against it” (1790/1952, p. 174). This demonstrates perceptions of the plastic as overtly attacking the viewer with its presence. This is supported by Ngai, in statements that “what makes the object abhorrent is precisely its outrageous claim for desirability. The disgusting seems to say, ‘You want me,’ imposing itself on the subject as something to be mingled with and perhaps even enjoyed” (2007, p. 335). Reactions of disgust, then, can be deduced as occurring only when the viewer strongly disagrees with what the object is presenting itself as, and as an offence to their person and worldviews. This suggests that the existence of the warped plastics affirmed participants’ dislike of plastic itself, and highlights a pre-existing ecological awareness in these participants. This reveals that participants who reacted with disgust still regarded these warped plastics through stereotypical consumer perceptions of plastic; the warping of these plastics did not facilitate new perspectives or ways of seeing the plastic beyond their normative definitions. It is likely, then, that these participants were so subsumed by their ecological hatred for plastic that they became closed off to further exploration.

Beautiful

The reaction of some participants to regard the plastic as beautiful is a stark contrast to the way plastic and plastic waste is usually perceived in consumer contexts. This highlights that the warping of these plastics shifted the prespectives of participants to regard plastic in new ways, and made them aware of the more material nature of plastic. It also highlights that the workshop itself provided a context removed from consumer mindsets, which allowed for alternative perspectives to emerge. Kant’s statement that a person’s reactions of ‘beautiful’ are made in response to “what simply pleases him” (1790/1952, p. 49) reveals that these participants positively responded to these plastics; they were engaged by the aesthetic and visual qualities of the warped plastics. These particular responses confirm my own considerations of the plastic as beautiful.

The statement of one participant that it was problematic to communicate these plastics as beautiful demonstrates a tension between being captivated by these forms and knowing that this warped plastic should not be admired. This highlights that the visual qualities of these plastics are engaging in ways that might challenge those with pre-existing ecological mindsets, and bring these discussions to the forefront. There seems to be a limit, however, to how much these aesthetic responses can impact others—Kant also describes reactions of ‘beautiful’ as being delight without interest (1790/1952, p. 50). This suggests that reactions of beauty do not facilitate much stimulation outside of the object itself. This supports my conclusion in earlier experiments that purely presenting plastic through aestheticised means cannot directly lead to ecological reflection in consumers.

Cool

Warren and Campbell state that reactions of ‘cool’ emerge “when its behaviors diverge from the norm” (2014, p. 543). The participants may have hence regarded the warped plastics as ‘cool’ because it was unfamiliar and outside the norm. These responses support my hypothesis in this research that warped plastics can be used to challenge normative conventions. These responses also highlight that participants were responding to more than the aesthetic of these warped plastics; they began to engage conceptually with what this plastic represented.

Interesting

Responses of ‘interesting’ also signify a conceptual reaction in participants, and mark a response to the “relatively small surprise of information or variation from an existing norm” (Ngai, 2012, p. 5). The ‘interesting’ is defined by the occurrence of new information and the way this interacts with pre-existing worldviews—“the interesting marks a tension between the unknown and the already known” (Ngai, 2012, p. 5). This definition of interest as a “collision” or “contradiction” (Ngai, 2012, p. 12) illuminates that participants who expressed these reactions were challenged by the plastics in some way through exposure to their existence. This once again confirms that these warped plastics successfully caused shifts in participants. However, Ngai’s statements that these responses are “trivial” (2012, p. 18) suggest that the participants were only slightly impacted by the presence of these plastics. This in turn reveals that being in the presence of these warped plastic artefacts are not enough to powerfully evoke shifts in participants—but are perhaps enough to trigger thought, conversation and reflection.

Disgust

Instances of disgust and hatred in participants can be interpreted through Kant’s theory that disgust is an object “insisting, as it were, upon our enjoying it, while we still set our face against it” (1790/1952, p. 174). This demonstrates perceptions of the plastic as overtly attacking the viewer with its presence. This is supported by Ngai, in statements that “what makes the object abhorrent is precisely its outrageous claim for desirability. The disgusting seems to say, ‘You want me,’ imposing itself on the subject as something to be mingled with and perhaps even enjoyed” (2007, p. 335). Reactions of disgust, then, can be deduced as occurring only when the viewer strongly disagrees with what the object is presenting itself as, and as an offence to their person and worldviews. This suggests that the existence of the warped plastics affirmed participants’ dislike of plastic itself, and highlights a pre-existing ecological awareness in these participants. This reveals that participants who reacted with disgust still regarded these warped plastics through stereotypical consumer perceptions of plastic; the warping of these plastics did not facilitate new perspectives or ways of seeing the plastic beyond their normative definitions. It is likely, then, that these participants were so subsumed by their ecological hatred for plastic that they became closed off to further exploration.

Conclusion

Did interacting with the warped plastics engage participants?

While the responses of majority of the participants confirm and support the idea that warped plastic can evoke conversation and thought in them, the absence of response from some of the participants is something to note as well. This, combined with the difference in reaction between participants to the warped plastics, highlights that the plastics do not affect participants universally or in the same way, and that the they do not automatically cause shifts in perception in participants.

The responses of participants who did react reveal that the warped plastics did not facilitate shifts toward understandings of the longevity of plastic specifically. The ‘image’ or ‘visual’ of these plastics alone are therefore not enough to encourage these shifts in participants. This further proves that the assumptions behind my photographic experiments in Approach One—that visualising and portraying the warped plastics could shift change in consumers—were incomplete, and supports the decision to move on to storytelling approaches.

While the responses of majority of the participants confirm and support the idea that warped plastic can evoke conversation and thought in them, the absence of response from some of the participants is something to note as well. This, combined with the difference in reaction between participants to the warped plastics, highlights that the plastics do not affect participants universally or in the same way, and that the they do not automatically cause shifts in perception in participants.

The responses of participants who did react reveal that the warped plastics did not facilitate shifts toward understandings of the longevity of plastic specifically. The ‘image’ or ‘visual’ of these plastics alone are therefore not enough to encourage these shifts in participants. This further proves that the assumptions behind my photographic experiments in Approach One—that visualising and portraying the warped plastics could shift change in consumers—were incomplete, and supports the decision to move on to storytelling approaches.

Part Two

Stories from the Afterlife Final Workshop results

This section details the results from the Stories from the Afterlife Final Workshop. I particularly highlight that the results from the Final Workshop differed from those of the Trial Workshops. Unlike Trial Workshops, participants in this Final Workshop did not explore or discuss ideas of the longevity of plastic waste. In this section I explore and unpack why these responses may have differed. I divulge that participant responses to storytelling prompts, and participant responses to prompts of custodianship, revealed a pre-established human-centred approach to plastic in majority of the Final Workshop participants. From this, I identify specific participant personas that the workshops are most and least effective in engaging.

Participant responses to storytelling prompts

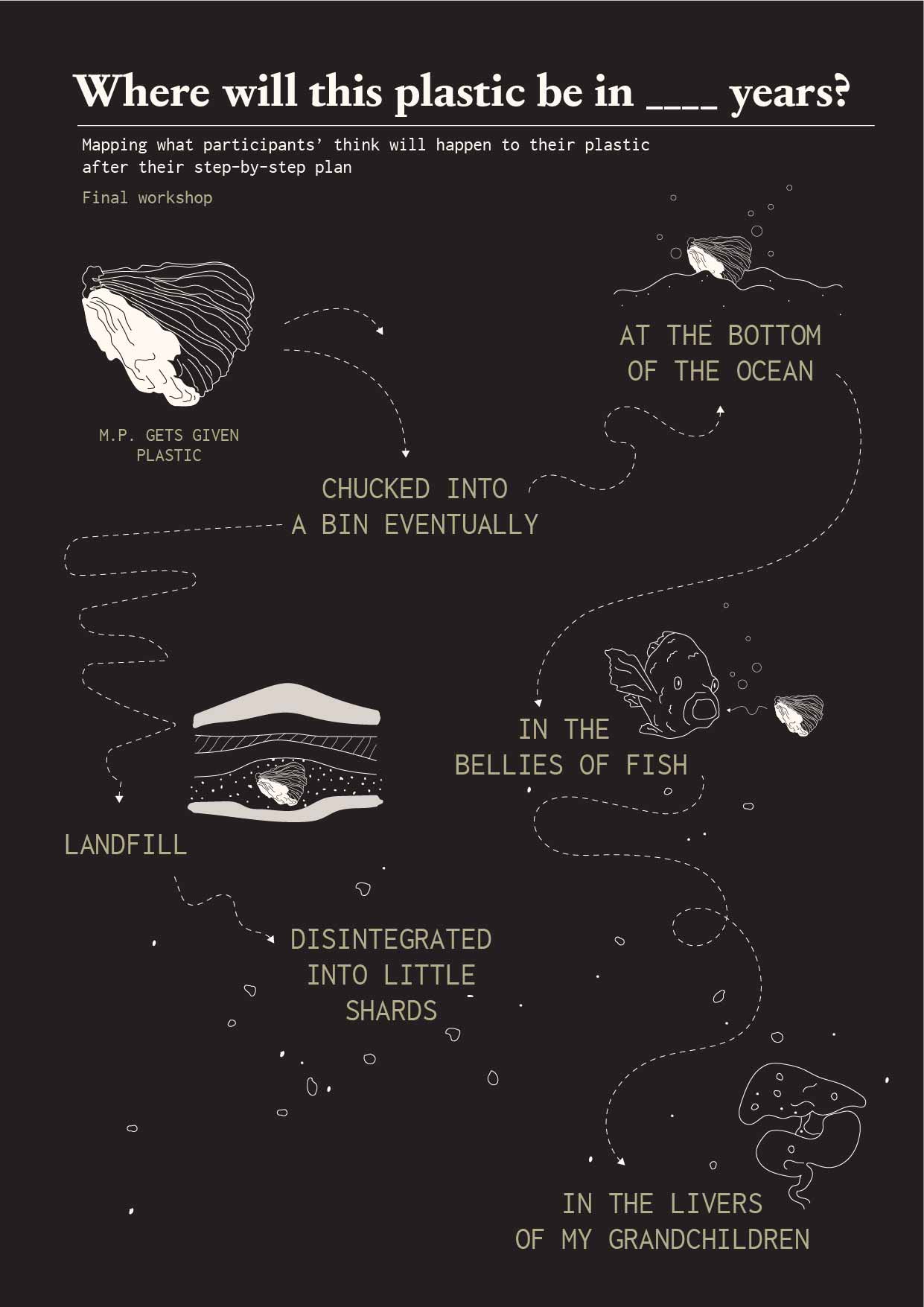

Storytelling prompts in this Final Workshop asked participants to map and consider the 1 year, 10 year, 100 year and 1,000 year future of a warped plastic they had chosen (Figure 76). Participant responses to these prompts followed predominantly human-centred perspectives. There is a focus in their responses on how future technological innovation can manipulate and respond to problems of waste. This solutions-focused perspective is central even in mentions of outer space—which, while used more fictitiously and humorously in previous Trial Workshops—are discussed in this workshop as a potential solution avenue:

“Can we put them up on asteroids? What are the space ethics of sending plastic out to space?”

— Participant statement

And while the 1,000 year discussions exhibit consideration of how plastic may have transformed (Figure 76), these transformations are attributed to events of human manipulation and advancements in waste infrastructures. Due to this more solutions-based mentality, nonhuman thought therefore did not enter the discussion. Discussions and realisation of the deep timescale of plastic were also not overtly present, perhaps as a result of participants speculating within a human-centred worldview, which prevented opportunities for nonhuman ontologies to surface. Their interpretation of the prompts and the plastic were grounded in a desire for a tangible solution to the issue of plastics and consumption in general. This brings into question whether pre-existing knowledge or familiarity with the issue of plastic impacts on participants’ abilities to embrace alternative perspectives in the form of nonhuman ontologies.

“Can we put them up on asteroids? What are the space ethics of sending plastic out to space?”

— Participant statement

And while the 1,000 year discussions exhibit consideration of how plastic may have transformed (Figure 76), these transformations are attributed to events of human manipulation and advancements in waste infrastructures. Due to this more solutions-based mentality, nonhuman thought therefore did not enter the discussion. Discussions and realisation of the deep timescale of plastic were also not overtly present, perhaps as a result of participants speculating within a human-centred worldview, which prevented opportunities for nonhuman ontologies to surface. Their interpretation of the prompts and the plastic were grounded in a desire for a tangible solution to the issue of plastics and consumption in general. This brings into question whether pre-existing knowledge or familiarity with the issue of plastic impacts on participants’ abilities to embrace alternative perspectives in the form of nonhuman ontologies.

Participant responses to custodianship

When given hypothetical custodianship of their plastic, two out of the three participants immediately stated their desire to dispose of it. They regarded their plastic as having fully served its function:

“I’m not going to do anything with it. It’s run its course.” — Participant statement

Participants once again focused discussions on future technological innovations in response to custodianship prompts. Custodianship of the plastic did not facilitate impactful considerations of deep time in participants, nor did it facilitate discussions around how their actions of disposing this plastic would have deep time ramifications. The tendency of the participants in this group to remain unaffected by the workshop prompts are made even more apparent in their responses to the follow-up survey, and in their descriptions of what they gained from the workshop.

“I’m not going to do anything with it. It’s run its course.” — Participant statement

Participants once again focused discussions on future technological innovations in response to custodianship prompts. Custodianship of the plastic did not facilitate impactful considerations of deep time in participants, nor did it facilitate discussions around how their actions of disposing this plastic would have deep time ramifications. The tendency of the participants in this group to remain unaffected by the workshop prompts are made even more apparent in their responses to the follow-up survey, and in their descriptions of what they gained from the workshop.

Impact of the workshop on participants

For one participant, storytelling about their plastic succeeded in enabling them to visualise the ongoing impacts of plastic. This made them more motivated to change their behaviours, and highlights that these workshops can facilitate ecological responses in participants.

For the other two participants, however, the workshops only affirmed what they already knew. One of these participants even expressed surprise that there were other worldviews than their own and specifically stated that they were not changed in any way because they were already familiar with fields of sustainability. This perhaps explains why deep time considerations were not fully present in the workshop; having a familiarity with plastic limited their exploration of these concepts. This once again points to how a pre-existing familiarity and expertise with plastic can limit how much a participant is open to exploring alternative framings and approaches to plastic.

Conclusion

The absence of deep time consideration and conversation amongst the participants of the Final Workshop highlights that the nature of the prompts may not be effective in visualising longevity for all participants. Considering Stoknes’ arguments that “different audiences need to hear different stories” (2015, p. 149), it is evident, then, that exploring the persistent afterlives of plastic as a way to access ecological thought is not suitable for all participants. These results serve as a reminder that we cannot design for everyone (Martin & Hanington, 2012, p. 132). The difference in response in terms of impact from these participants highlights that these workshops may only affect a specific type of participant, as outlined below.

Conclusions for Stories from the Afterlife

In summary, the responses of participants from all Stories from the Afterlife workshops revealed that:

These differences in response were not dependent—as I had previously hypothesised—on the disciplinary background of the participant; both those from creative fields and empirical fields did and did not adopt nonhuman scales of time. Instead, the measure of the workshop’s success seems to be determined by the pre-existing ecological awareness of participants. Participants who strongly identified as ecologically minded—like those in the Final Workshop—were less affected by concepts of time and did not engage in dialogue about nonhuman timelines or the afterlives of plastic. The participants in the Trial Workshops, in comparison, did embark on conversations around the nonhuman longevity of plastic. They were ecologically aware, but not to the extent of having dedicated their careers and personal behaviours to sustainability.

In reference to Martin and Hanington’s arguments that “attempting to design for everyone results in unfocused or incoherent solutions” (2012, p. 132), results such as these highlight that these workshops should recruit and design for specific types of individuals in mind. This builds on the ideas of Alan Cooper, specifically the development of personas (1999). Cooper states that a persona is “a precise description of our user and what he wishes to accomplish” (1999, p. 123), and that it is the development of these personas which make a design successful and relevant. Using the insights gained from the background of my participants, potential personas that these workshops do and do not cater to can be identified.

The factors identified earlier as influencing the participants’ response to the workshops display a similarity to Stoknes’ measure of social attitudes to climate change (2015, p. 58). As such, I will reference and adopt Stoknes’ social attitudes as personas for these workshops. Specifically, two of Stoknes’ attitudes align with the perceived mindsets of the participants who attended the Stories from the Afterlife workshops. These have been adjusted to better suit the values present in the workshops:

The Changemakers (originally ‘Alarmed’)

Stoknes describes those with attitudes of alarm as well-informed and as “convinced what is happening is human-caused, and feel it is a serious and urgent threat. The alarmed try to do something in their own lives and support aggressive national response” (2015, p. 58). This mentality aligns well with the participants of the Final Workshop who spoke with strong ecological opinions. For the context of this workshop, however, a defining factor amongst these participants was that they were researching or working within sustainable fields, and thus the nomenclature of this persona has been changed to the ‘changemaker’ to reflect this specific criteria. These are the participants who were unaffected by the workshop designs and did not engage in nonhuman thought or conversation. They are thus not ideal participants for future workshops.

The Concerned

Stoknes’ description of the concerned is that they acknowledge it “is a serious problem and are moderately well informed about the issue….They are distinctly less involved in the issue—and less likely to be taking personal action” (Stoknes, 2015, p. 58). This somewhat aligns with the attitudes and responses of the participants of the Trial Workshops. Unlike Stoknes’ classifications, however, many of these participants were undertaking small personal changes every now and then. As such, references to personas of the ‘Concerned’ will re-appropriate Stoknes’ definitions to include personal action.

These personas begin to highlight the limits and scope of the Stories from the Afterlife workshops; it highlights that the workshop is only effective for particular personas—the ‘Concerned’. This demonstrates that the ideal participants for these workshops are those that have pre-existing ecological thought, but are not consumed by their ecological concern. The results from Stories from the Afterlife hence proves that this workshop design can build on pre-established concerns for those who are open to ecological change, but by no means experts.

- Some participants reacted to the warped plastics while others did not

- The workshop encouraged some of the participants to consider the nonhuman ways plastic persists without end, but not all

- The workshop facilitated ecological shifts in some participants, but not all

These differences in response were not dependent—as I had previously hypothesised—on the disciplinary background of the participant; both those from creative fields and empirical fields did and did not adopt nonhuman scales of time. Instead, the measure of the workshop’s success seems to be determined by the pre-existing ecological awareness of participants. Participants who strongly identified as ecologically minded—like those in the Final Workshop—were less affected by concepts of time and did not engage in dialogue about nonhuman timelines or the afterlives of plastic. The participants in the Trial Workshops, in comparison, did embark on conversations around the nonhuman longevity of plastic. They were ecologically aware, but not to the extent of having dedicated their careers and personal behaviours to sustainability.

In reference to Martin and Hanington’s arguments that “attempting to design for everyone results in unfocused or incoherent solutions” (2012, p. 132), results such as these highlight that these workshops should recruit and design for specific types of individuals in mind. This builds on the ideas of Alan Cooper, specifically the development of personas (1999). Cooper states that a persona is “a precise description of our user and what he wishes to accomplish” (1999, p. 123), and that it is the development of these personas which make a design successful and relevant. Using the insights gained from the background of my participants, potential personas that these workshops do and do not cater to can be identified.

The factors identified earlier as influencing the participants’ response to the workshops display a similarity to Stoknes’ measure of social attitudes to climate change (2015, p. 58). As such, I will reference and adopt Stoknes’ social attitudes as personas for these workshops. Specifically, two of Stoknes’ attitudes align with the perceived mindsets of the participants who attended the Stories from the Afterlife workshops. These have been adjusted to better suit the values present in the workshops:

The Changemakers (originally ‘Alarmed’)

Stoknes describes those with attitudes of alarm as well-informed and as “convinced what is happening is human-caused, and feel it is a serious and urgent threat. The alarmed try to do something in their own lives and support aggressive national response” (2015, p. 58). This mentality aligns well with the participants of the Final Workshop who spoke with strong ecological opinions. For the context of this workshop, however, a defining factor amongst these participants was that they were researching or working within sustainable fields, and thus the nomenclature of this persona has been changed to the ‘changemaker’ to reflect this specific criteria. These are the participants who were unaffected by the workshop designs and did not engage in nonhuman thought or conversation. They are thus not ideal participants for future workshops.

The Concerned

Stoknes’ description of the concerned is that they acknowledge it “is a serious problem and are moderately well informed about the issue….They are distinctly less involved in the issue—and less likely to be taking personal action” (Stoknes, 2015, p. 58). This somewhat aligns with the attitudes and responses of the participants of the Trial Workshops. Unlike Stoknes’ classifications, however, many of these participants were undertaking small personal changes every now and then. As such, references to personas of the ‘Concerned’ will re-appropriate Stoknes’ definitions to include personal action.

These personas begin to highlight the limits and scope of the Stories from the Afterlife workshops; it highlights that the workshop is only effective for particular personas—the ‘Concerned’. This demonstrates that the ideal participants for these workshops are those that have pre-existing ecological thought, but are not consumed by their ecological concern. The results from Stories from the Afterlife hence proves that this workshop design can build on pre-established concerns for those who are open to ecological change, but by no means experts.

Part Three

What Now? Final Workshop results

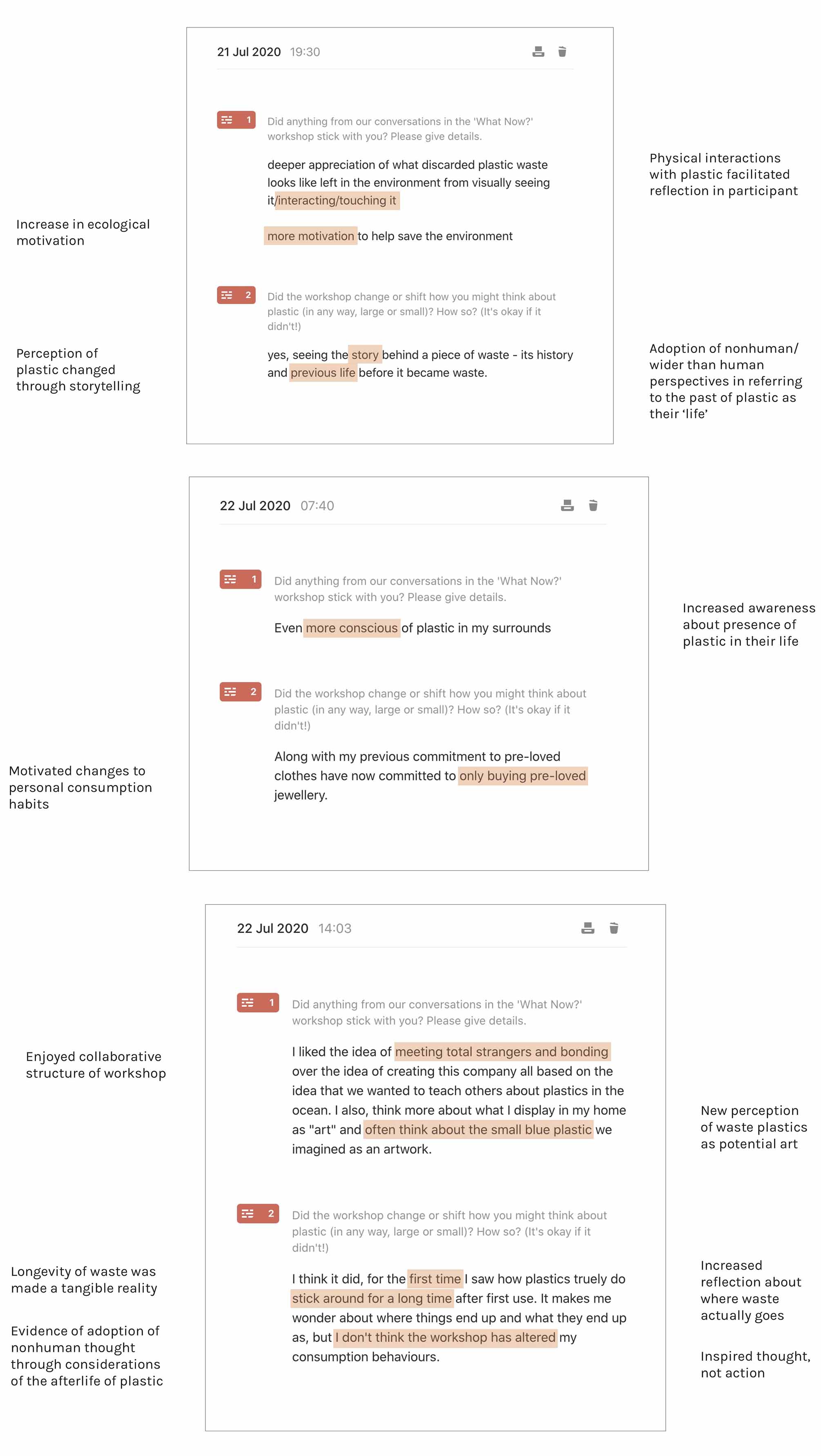

In this section I detail the results of the What Now? Final Workshop to determine the impact of the workshop and its storytelling prompts on participants. Similar to Trial Workshop participants, the participants of this Final Workshop engaged in ecological and nonhuman considerations about plastic. I consider how prescribing custodianship of plastic onto participants and how mapping the deep future timelines of plastic particularly achieved this result.

Participant responses to custodianship

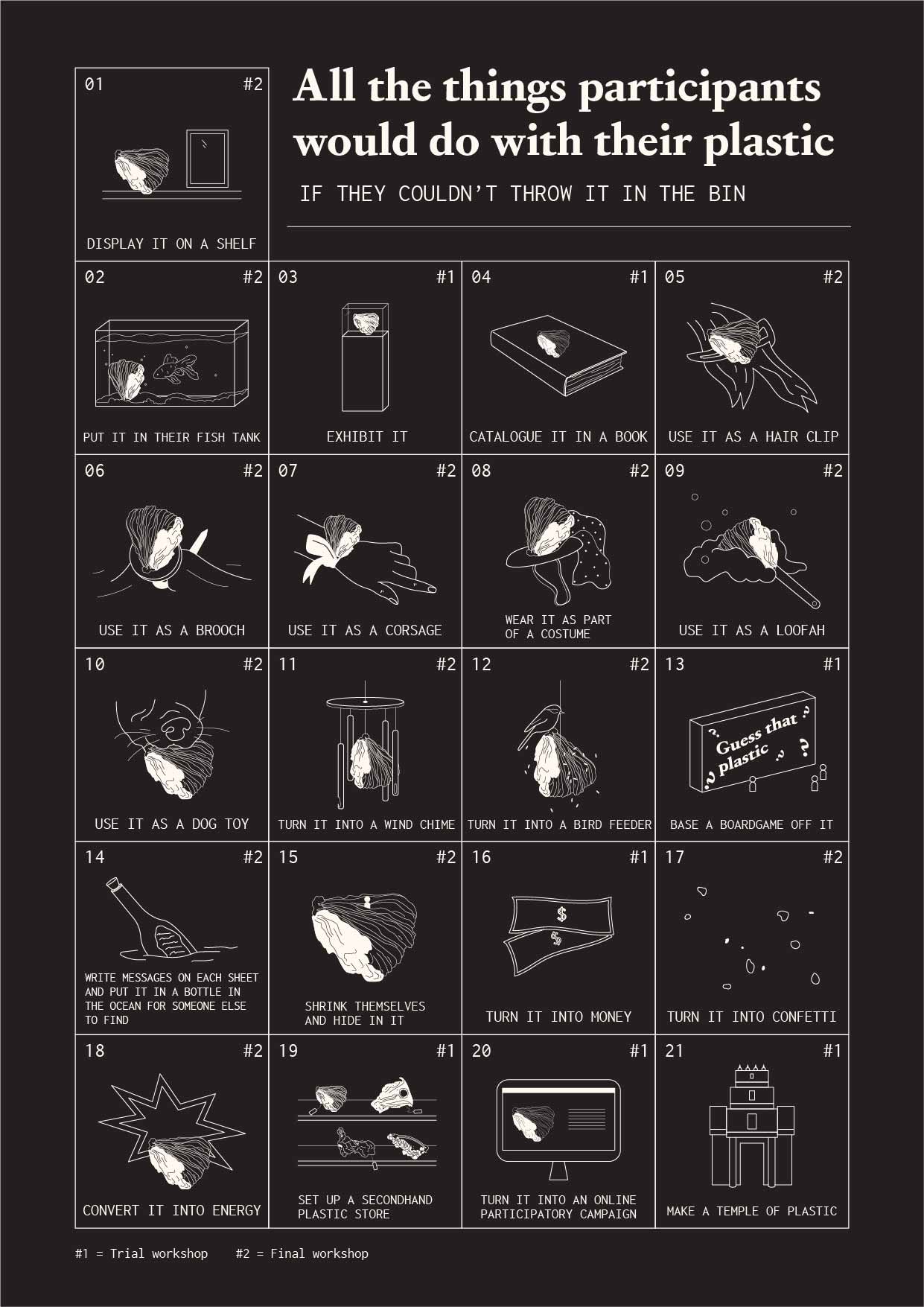

Comparing the responses to custodianship between Trial and Final Workshops (Figure 78) reveals a range of responses to custodianship; from re-using their plastic for individual use (like the loofah) to re-using their plastic on a wider human scale (like converting it into energy or money). Their responses exist within fictional scenarios (jokingly discussed, and clearly never to be executed), which highlights how outside the norm this idea is and how difficult it is to give plastic another life.

“An aquarium with plastic building up on the bottom and then you go out and go ‘oh I forgot my KeepCup’, or that day you choose to buy lunch and go ‘oh why has this got so much plastic on it? I’ll choose that lunch.’” — Participant statement

The participants’ idea to use their warped plastic to change perceptions and facilitate ecological awareness strikingly mirrors both my own positions in this research and the responses of participants from the What Now? Trial Workshop. This similarity in thought demonstrates a commonality in response in wanting to use the warped plastics for ecological change, and also highlights that participants can interpret ecological messages within the plastic.

When prompted to consider what they would do with their plastic after this plan, however, one participant stated that they couldn’t keep maintaining custodianship of their plastic for that long:

“I’m not even emotionally attached to this even though we picked it out from there.”

— Participant statement

Their wish to eschew continued responsibility and custodianship of their plastic highlights just how difficult it can be to want to keep plastic and not dispose of it. It also highlights how custodianship made them anxious in realising how long they would need to keep maintaining the plastic for. Custodianship was hence effective in shifting participants to personally realise the longevity of plastic.

Participant responses to storytelling prompts

Participants, however, did initially display difficulty in answering these prompts, and began to segue to other topics. This was acknowledged by more than one participant, in realising that they did not answer the prompts fully:

“I noticed we sort of avoided some of your questions a bit because they’re so hard. ‘Where will plastic be in 100 years?’ and we just talked about stuff for a while. ‘Landfill, that’s where it’s going to be’.”

— Participant statement

Their initial avoidance of questions about the afterlife of plastic demonstrates that thinking about the multi-generational and persistent presence of plastic does not come naturally to participants, and that it is difficult to become de-centred from an immediate human reality.

Impact of the workshop on participants

One participant was affected by interacting with the physical artefacts of the plastic and of considering the past life of these plastics, while another was affected by the discussions of plastic itself. The third participant was particularly affected by the collaborative nature of the workshop. This demonstrates how different elements of the workshop spoke to different participants.

Their responses also reveal that ecological thought was facilitated through the workshops. Two participants expressed an increased ecological motivation—with one participant in particular identifying changes they could make to their own consumption habits—while the third participant expressed increased ecological awareness and thought. These shifts, again, refer to general ecological changes rather than plastic-specific ones, further highlighting that conversations around plastic ultimately also lead to conversations around sustainability and environmentalism. Their responses reiterate that these workshops can facilitate either increased motivation to act or increased thought in participants.

Conclusion

The results of this workshop demonstrate that an understanding of the persistent afterlives of plastic was successfully facilitated through the nature of the prompts and workshop. This was attributed mainly to questions of time, which challenged the immediate worldviews of participants and led them to adopt nonhuman understandings of time.

What is interesting about this particular workshop is that unlike the previous Trial Workshop, not all participants perceived themselves as ecologically minded—one participant reflected during discussion that they were currently at the “first step” of ecological behaviour and that they had “only” bought a KeepCup the previous year. This illustrates that the collaborative and conversational design of the workshop can facilitate an awareness in participants about their own behaviours by bringing to light how others behave. It also reveals a potential third persona type amongst participants; the ‘Cautious’. Once again, Stoknes’ measure of social attitudes is referred to in the naming and classification of this participant type:

The Cautious

These individuals think plastic “is a problem, but are not certain. They have given some thought to the issue, but not extensively. They don’t view it as a personal threat, and don’t feel a sense of urgency to do much about it. Other concerns get a higher priority” (Stoknes, 2015, p. 58).

This is distinctly different to the values of the other participants in this workshop, who best align with personas of ‘Concerned’ and ‘Changemaker’.

What is interesting about this particular workshop is that unlike the previous Trial Workshop, not all participants perceived themselves as ecologically minded—one participant reflected during discussion that they were currently at the “first step” of ecological behaviour and that they had “only” bought a KeepCup the previous year. This illustrates that the collaborative and conversational design of the workshop can facilitate an awareness in participants about their own behaviours by bringing to light how others behave. It also reveals a potential third persona type amongst participants; the ‘Cautious’. Once again, Stoknes’ measure of social attitudes is referred to in the naming and classification of this participant type:

The Cautious

These individuals think plastic “is a problem, but are not certain. They have given some thought to the issue, but not extensively. They don’t view it as a personal threat, and don’t feel a sense of urgency to do much about it. Other concerns get a higher priority” (Stoknes, 2015, p. 58).

This is distinctly different to the values of the other participants in this workshop, who best align with personas of ‘Concerned’ and ‘Changemaker’.

Conclusions for What Now?

All participants from the What Now? workshops were shifted in some way—with their responses highlighting either a motivation to change actions or an increased motivation to think through topics of waste and consumption. This demonstrates that the workshop facilitated individual and personal change in participants. This workshop was therefore successful in its aim of bringing the longevity of plastic into the consciousness of participants through custodianship and nonhuman storytelling. The difference of results between participants of the Trial and Final Workshops, however, suggests that the design of these workshops had a different impact on each individual.

While the results of Stories from the Afterlife suggested that somewhat ecologically aware (Concerned)—but not too ecologically minded (Changemakers)—participants were most impacted by its designs, the same cannot be said for the participant most like the ‘Changemaker’ persona in What Now?. This ‘Changemaker’ participant—strongly ecologically minded and researching within the field of sustainability—was impacted by the workshop, unlike those with similar attributes in Stories from the Afterlife.

The difference between ‘Changemaker’ participants in each workshop may depend on how well-informed about the issue of plastic they perceive themselves to be. They can therefore be distinguished by how open-minded and willing they are to obtain different points of view. This is evidenced in the difference in responses between ‘Changemaker’ participants; Stories from the Afterlife ‘Changemaker’ participants stated that the workshop affirmed their own views about plastic, while the What Now? ‘Changemaker’ participant stated that they learned new understandings from the workshop. This once again raises the question of whether the amount of knowledge one possesses about plastic can narrow their worldview and hinder their ability to explore different framings of the problem. The evidence of this disparity means that an adjustment to the participant personas is required:

The Close-minded Changemaker

Refers to those who are well-informed about the problem of plastic and “convinced what is happening is human-caused, and feel it is a serious and urgent threat. The alarmed try to do something in their own lives and support aggressive national response” (Stoknes, 2015, p. 58). Individuals within this persona are researching or working within sustainable fields, and believe they have an extensive understanding of the issue. The result of this is a difficulty to explore perspectives that are alternative to theirs.

The Open-minded Changemaker

These participants are similarly well-informed and motivated as the ‘Changemakers’ above, and are researching/working within sustainable practices. The difference is that unlike the more close-minded or ‘veteran’ changemakers, the ‘Open-minded Changemakers’ still believe they have more to learn about the issue. They are thus open to both sharing and receiving other perspectives.

The Concerned

Identifies those who recognise plastic as a concern in their daily life and make small changes to their behaviours to contribute to the issue.

The Cautious

Are aware about the issue of plastic, but not well-informed about the scope and specifics of it. They have undertaken little, if any, personal response to the issue, but are open to change.

Of the four personas present during the workshops, it is the latter three which the workshops most effectively impacted.

While the results of Stories from the Afterlife suggested that somewhat ecologically aware (Concerned)—but not too ecologically minded (Changemakers)—participants were most impacted by its designs, the same cannot be said for the participant most like the ‘Changemaker’ persona in What Now?. This ‘Changemaker’ participant—strongly ecologically minded and researching within the field of sustainability—was impacted by the workshop, unlike those with similar attributes in Stories from the Afterlife.

The difference between ‘Changemaker’ participants in each workshop may depend on how well-informed about the issue of plastic they perceive themselves to be. They can therefore be distinguished by how open-minded and willing they are to obtain different points of view. This is evidenced in the difference in responses between ‘Changemaker’ participants; Stories from the Afterlife ‘Changemaker’ participants stated that the workshop affirmed their own views about plastic, while the What Now? ‘Changemaker’ participant stated that they learned new understandings from the workshop. This once again raises the question of whether the amount of knowledge one possesses about plastic can narrow their worldview and hinder their ability to explore different framings of the problem. The evidence of this disparity means that an adjustment to the participant personas is required:

The Close-minded Changemaker

Refers to those who are well-informed about the problem of plastic and “convinced what is happening is human-caused, and feel it is a serious and urgent threat. The alarmed try to do something in their own lives and support aggressive national response” (Stoknes, 2015, p. 58). Individuals within this persona are researching or working within sustainable fields, and believe they have an extensive understanding of the issue. The result of this is a difficulty to explore perspectives that are alternative to theirs.

The Open-minded Changemaker

These participants are similarly well-informed and motivated as the ‘Changemakers’ above, and are researching/working within sustainable practices. The difference is that unlike the more close-minded or ‘veteran’ changemakers, the ‘Open-minded Changemakers’ still believe they have more to learn about the issue. They are thus open to both sharing and receiving other perspectives.

The Concerned

Identifies those who recognise plastic as a concern in their daily life and make small changes to their behaviours to contribute to the issue.

The Cautious

Are aware about the issue of plastic, but not well-informed about the scope and specifics of it. They have undertaken little, if any, personal response to the issue, but are open to change.

Of the four personas present during the workshops, it is the latter three which the workshops most effectively impacted.

Part Four

A reflection on workshop findings

Limitations

The workshops trialled in this research reflect a small sample size of participants, and are therefore still largely inconclusive in their insights. The participants present at these workshops represent a particular demographic of individual—while they differed in age, educational background, gender and cultural identity, the participants had all completed an undergraduate degree recently (within 5 years), or were undertaking Higher Degree Research. This commonality of a university education implies that the workshops were biased towards particular participants.

The difference in results and impact amongst participants also highlighted the limitations of these workshops in affecting certain types of participants. In previous conclusions, particular ecological mindsets were identified which the workshops impacted most; the ‘Cautious’, the ‘Concerned’ and the ‘Open-minded Changemaker’. While this begins to demonstrate the scope of participants that these workshops can effectively impact change within and is something to consider in the recruitment of future participants, this is only a precursory understanding of the factors that can influence participant responses to the workshops. Testing these workshops with a broader range of participants would clarify these factors further.

The difference in results and impact amongst participants also highlighted the limitations of these workshops in affecting certain types of participants. In previous conclusions, particular ecological mindsets were identified which the workshops impacted most; the ‘Cautious’, the ‘Concerned’ and the ‘Open-minded Changemaker’. While this begins to demonstrate the scope of participants that these workshops can effectively impact change within and is something to consider in the recruitment of future participants, this is only a precursory understanding of the factors that can influence participant responses to the workshops. Testing these workshops with a broader range of participants would clarify these factors further.

Workshop conclusion and future considerations for this research

These workshops highlight that participatory design can be used to facilitate speculative storytelling and conversation about the persistent existence of plastic, which can shift consumer perceptions of plastic’s disposability. This confirms that my methods of experimentation and story generation—which were translated into workshop prompts—are suitable for generating understandings of the longevity of plastic waste for some consumers. It also confirms that thinking through the lifespan of plastic can stimulate ecological reflection in them. Most notably, it was the conversational structure of these workshops which allowed many of the participants to give voice to these ideas and concerns, and to share them in a mutual ecological discussion about deep time longevity.

This highlights potential for these workshops to be repeated with different and wider groups of participants, and suggests a path forwards should this research be continued in the future. In their ability to facilitate nonhuman story generation and a consideration of the deeper timelines of plastic in some participants, these workshops also make arguments that participatory design workshops can execute and disseminate the theories of Bennett, Tsing, Colebrook and Stoknes.

Further clarification, however, is needed on whether the outcomes of a workshop depend on the professional background of the participants, and whether having more knowledge about plastic can limit the ability to adopt alternative perceptions and worldviews. Including more demographics of participants will better define the personas that the workshops best speak to, and will give better indication of the impacts of the workshops. This is something to consider for future workshops.

The majority of participants also exhibited a distinct lack of connection to the plastic—no one was particularly excited at the prospect of custodianship. Future workshops could consider changing how participants are introduced to the plastic—is it possible to get people to search for and bring in their own piece of collected plastic? Will this inspire further ownership? From this, it is clear that there is still more to consider with these workshops, and more experimentation to be done in the future. A wide circulation and dissemination of these workshops—like Wertheim and Wertheim’s Crochet Coral Reef project (2015)—would assist in clarifying the workshop designs. It would also assist with continuing to build on the seeds of change begun with these workshops.

This highlights potential for these workshops to be repeated with different and wider groups of participants, and suggests a path forwards should this research be continued in the future. In their ability to facilitate nonhuman story generation and a consideration of the deeper timelines of plastic in some participants, these workshops also make arguments that participatory design workshops can execute and disseminate the theories of Bennett, Tsing, Colebrook and Stoknes.

Further clarification, however, is needed on whether the outcomes of a workshop depend on the professional background of the participants, and whether having more knowledge about plastic can limit the ability to adopt alternative perceptions and worldviews. Including more demographics of participants will better define the personas that the workshops best speak to, and will give better indication of the impacts of the workshops. This is something to consider for future workshops.

The majority of participants also exhibited a distinct lack of connection to the plastic—no one was particularly excited at the prospect of custodianship. Future workshops could consider changing how participants are introduced to the plastic—is it possible to get people to search for and bring in their own piece of collected plastic? Will this inspire further ownership? From this, it is clear that there is still more to consider with these workshops, and more experimentation to be done in the future. A wide circulation and dissemination of these workshops—like Wertheim and Wertheim’s Crochet Coral Reef project (2015)—would assist in clarifying the workshop designs. It would also assist with continuing to build on the seeds of change begun with these workshops.