Approach One:

Photographic Stories

This approach uses the medium of photography to share and communicate the existence of the warped plastics. It uses Bennett’s question—“how, for example, would patterns of consumption change if we faced not litter, rubbish, trash, or ‘the recycling’, but an accumulating pile of lively and potentially dangerous matter?” (2010, p. viii)—to drive the intent behind this approach; to frame the warped plastics as evidence of the ‘lively’ existences of post-use plastics. Photography is used as a vehicle to present a ‘lifelike’ or ‘true-to-eye’ account of these plastics; providing ‘visual evidence’ for the longevity and liveliness of plastics through its material warping. This approach is framed around creating outcomes to disseminate to consumer audiences as a way of raising awareness and dialogue about the longevity of plastic, and thus inspiring ecological concern.

In reference to psychologist Per Espen Stoknes’ argument that “people tend to disregard problems they cannot see or feel” (2015, p. 33), this approach to photography seeks to generate indisputable evidence for the indisposable nature of plastic. This approach fundamentally assumes that presenting unmanipulated, ‘true’ accounts of these warped plastics will be enough to persuade and encourage shifts in consumer perceptions about plastic.

Experiment

Live Matter

Aim

To photographically document the warped plastics in ways that provide visual evidence of how they exist and behave post-disposal—thereby promoting ideas that plastic waste doesn’t simply disappear because it is out of sight.

Precedents

This experiment uses Kelly Jazvac’s Plastiglomerate (2013) as a visual precedent. This has influenced this approach, where each piece of plastic was photographed individually in a studio environment. It has also influenced understandings that the visual ‘image’ of these warped plastics is enough to demonstrate the longevity of plastic for others.

It also adopts Bennett’s theories by considering these plastics as ‘lively’ (2010), and documents the warping of these plastics to demonstrate their ability to adapt and evolve through time.

It also adopts Bennett’s theories by considering these plastics as ‘lively’ (2010), and documents the warping of these plastics to demonstrate their ability to adapt and evolve through time.

Methods

The plastics were photographed individually in a photography studio setup. The decision to photograph them singularly was made in order to highlight how each plastic had warped in a different way. This was an attempt to make consumers see plastic as more than a consumer object, and instead engage them with the ‘lively’ (Bennett, 2010) ability of plastic to adapt and warp.

The resulting photographs were intended to be used as ‘facts’ to disseminate to consumers (Figure 1, 2, 3 & 4). They sought to facilitate the same astonishment, intrigue and unsettling realisations about the longevity of plastic that I felt when first encountering these plastics.

The resulting photographs were intended to be used as ‘facts’ to disseminate to consumers (Figure 1, 2, 3 & 4). They sought to facilitate the same astonishment, intrigue and unsettling realisations about the longevity of plastic that I felt when first encountering these plastics.

Reflection

The resulting series of photographs were stylistically too close to that of Plastiglomerate (Jazvac, 2013). This photographic style—a style similar to commercial product photography—ended up reducing the warped plastics into mere objects. My initial interpretations of these warped plastic forms was that they were visual expressions of the afterlives of plastic, and due to my focus on making them aesthetically pleasing, these photographs did not explore or highlight the intricacies of this material warping enough to make clear how plastics can adapt and behave post-use. As a result, I was sceptical whether these photographs would have much of an impact on viewers.

Insights

A different photographic aesthetic was needed to portray these plastics. The characteristics of their warping—the features that would best demonstrate their liveliness—also needed to be highlighted more evidently. This would require a closer inspection of each warped plastic to identify their warped features.

Experiment

A Visual Catalogue of Plastics

Aim

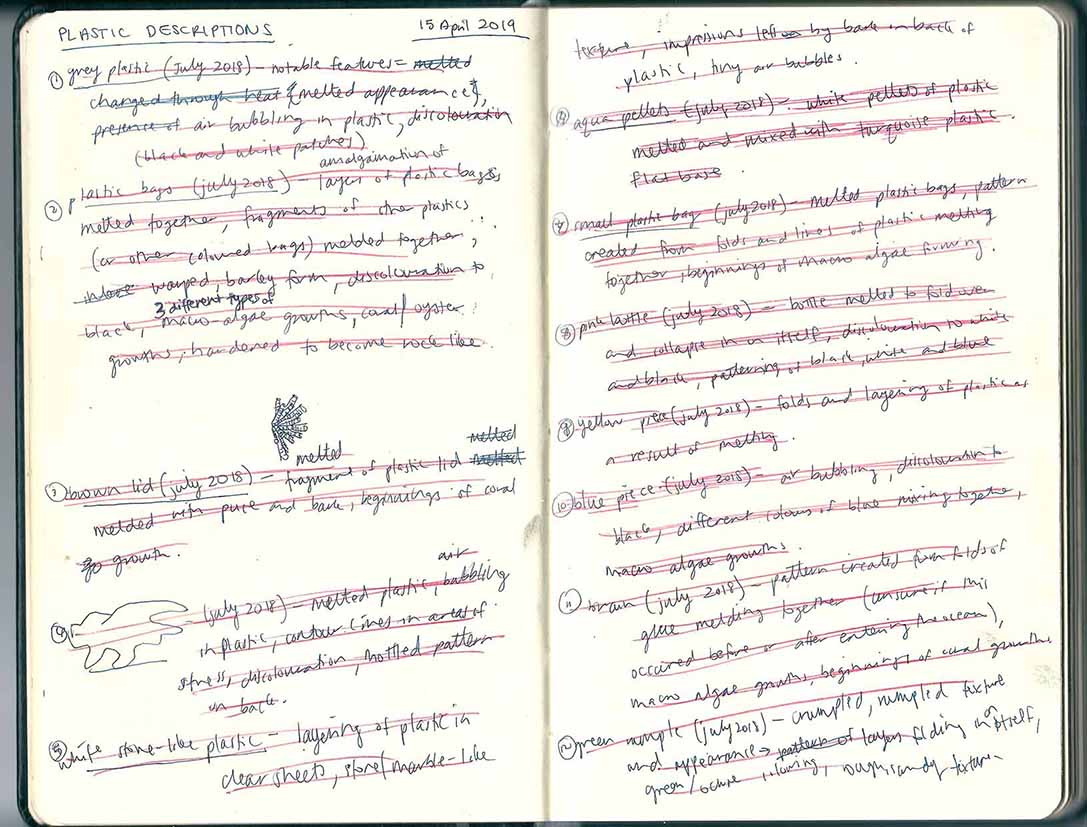

This experiment sought to document and display the warped materiality of the plastics in ways that made their ‘liveliness’ (Bennett, 2010) apparent. It assumed that systematically observing the plastics would reveal more engaging ways of framing and presenting them to consumers.

Precedents

While Experiment: Live Matter used photography to document the existence of post-use warped plastics as whole forms, I focused my efforts in this experiment to capture and understand how these plastics had warped, and why they were significant. This experiment also draws from the style of photography present in Mandy Barker’s Soup: Fragmented Cups (2012).

Methods

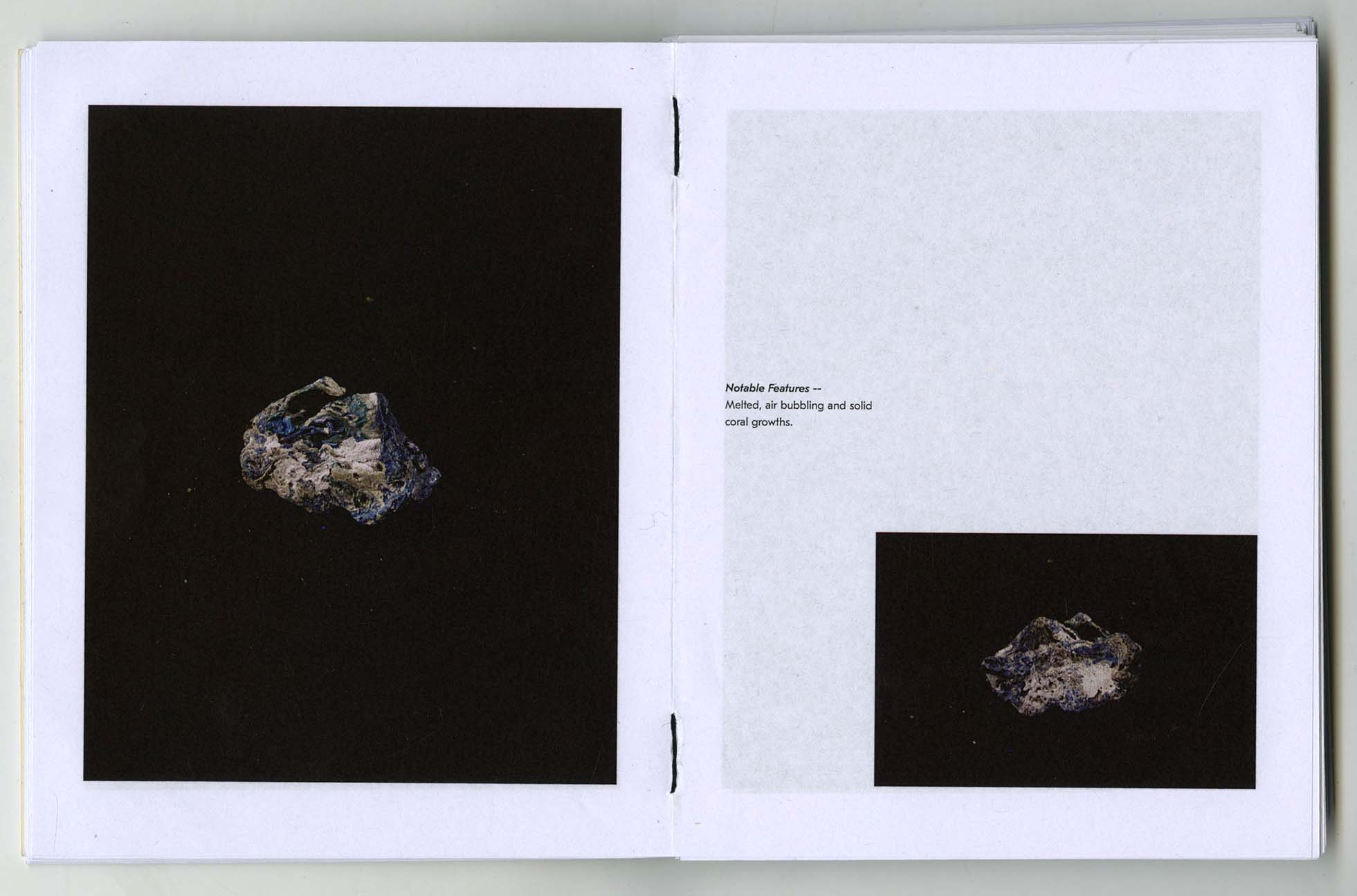

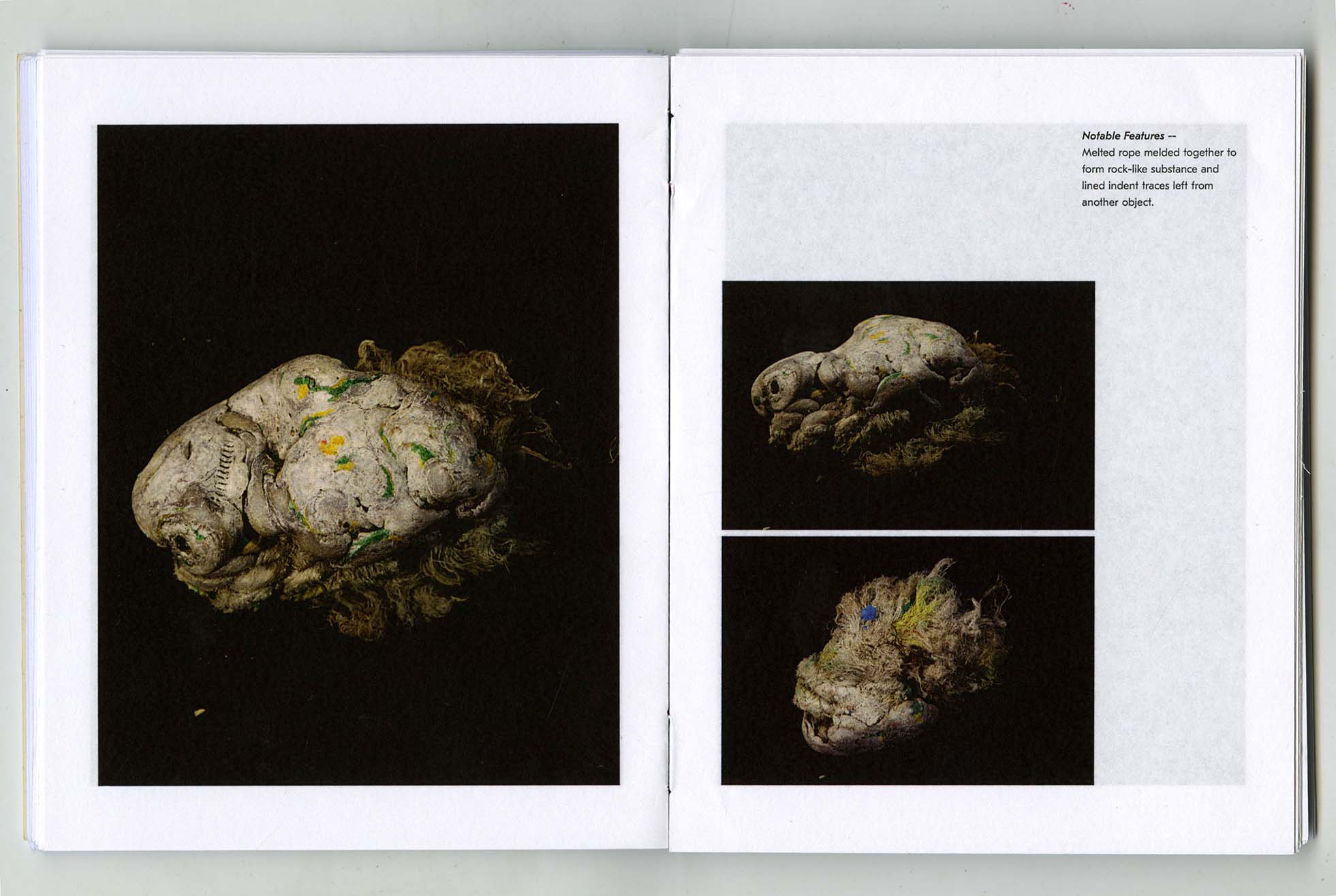

The plastics were photographed on a black background to move away from associations with product photography in the previous experiment. The movement of plastics on and off this darker backdrop made them shed small microplastics. This provided a ‘floating’ aesthetic to the photographs similar to Barker’s; as if they were submerged in deep sea or in space.

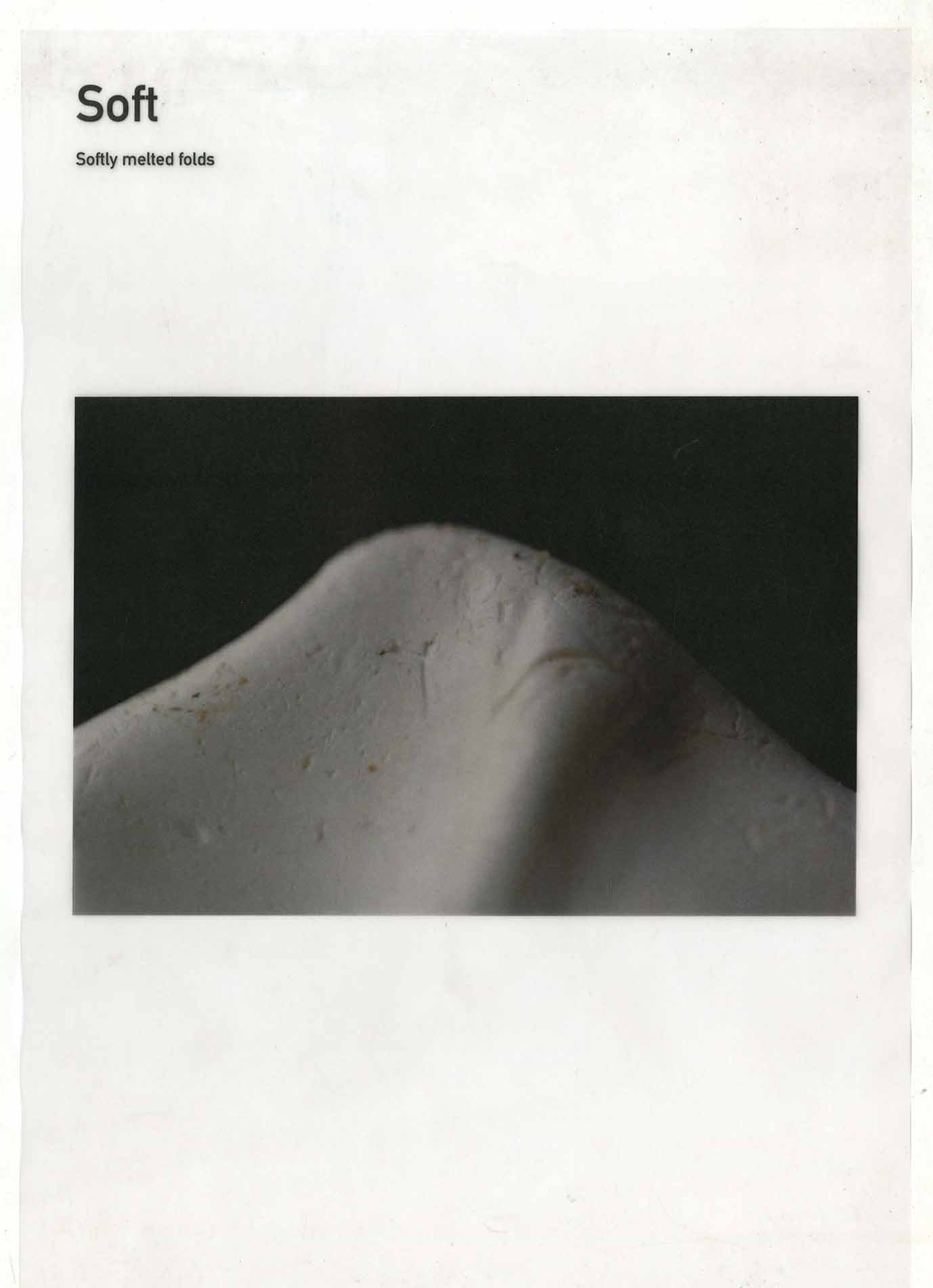

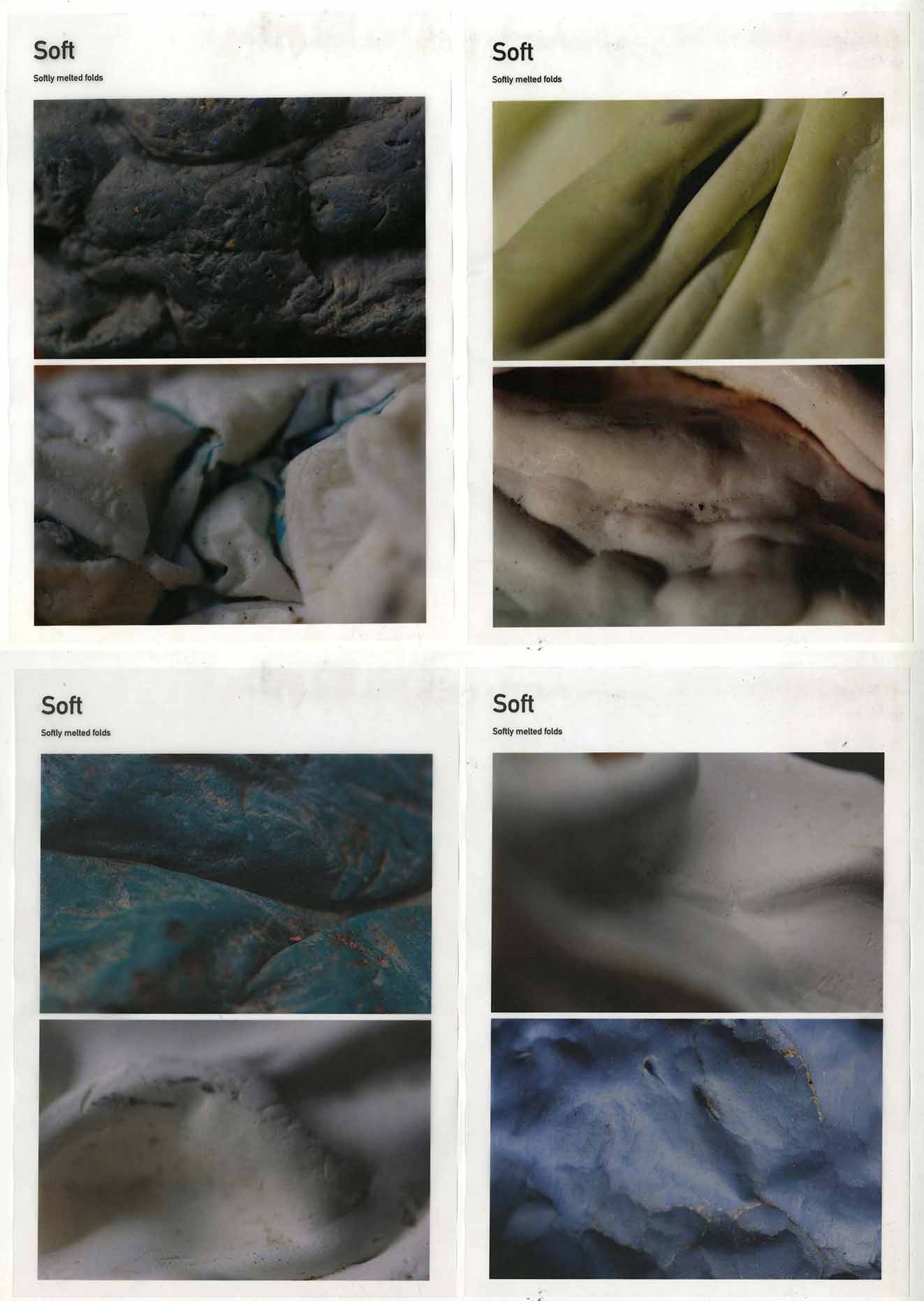

The photographs of the plastics in this experiment were displayed comparatively in a poster format (Figure 5). I knew, however, that the poster was a limiting form; the observations I had noted down could not be included in this outcome. I thus made an accompanying book to act as a compendium of these noticeable qualities, with annotated text serving to highlight the lively qualities of the plastic (Figure 6 & 7).

Reflection

Observing these plastics in more detail revealed the unseen landscapes that these plastics had become. This began to remove me from stereotypical consumer associations of plastic—as a staid object for human use—and opened up my imagination to realise that these plastics are entities rich with interaction and liveliness. The lens of the camera elevated this, and animated these plastics as subjects rather than objects; as things that were worthy of attention and interest. This process of observation began to shift my perspective outside of human worldviews, as it made me realise just how “entangled” (Tsing, 2015, p. viii) plastic waste can be with its environment outside of human contexts. This demonstrates that it was interacting with and handling (Bolt, 2007) the plastic which facilitated an ability to see the plastic as more than a consumer object.

The way these plastics were photographed ultimately reflected how I perceived them; as beautiful in their materiality. A concern voiced by supervisors and other academics, however, questioned whether this beautification would entice consumers to want to stop consuming plastic. My approach to photography which ‘staged’ these plastics like art thus needed to be reconsidered.

The way the warped characteristics of the plastics were identified in this experiment were also perhaps too subtle for a consumer viewer; it would require them to perform a detailed inspection of my outcome.

The way these plastics were photographed ultimately reflected how I perceived them; as beautiful in their materiality. A concern voiced by supervisors and other academics, however, questioned whether this beautification would entice consumers to want to stop consuming plastic. My approach to photography which ‘staged’ these plastics like art thus needed to be reconsidered.

The way the warped characteristics of the plastics were identified in this experiment were also perhaps too subtle for a consumer viewer; it would require them to perform a detailed inspection of my outcome.

Insights

Moving forward, I had two goals; to make these hidden worlds of the plastic more obvious, and to do so in a way that treated these plastics less like aestheticised objects of art, and more like lively beings. I hypothesised that using a macro lens would address both issues, as it would be able to capture the more intricate details of these plastics, and such a close zoom would eliminate the need for aesthetic backdrops and positionings.

Experiment

A Typology of Marine Organisms

Aim

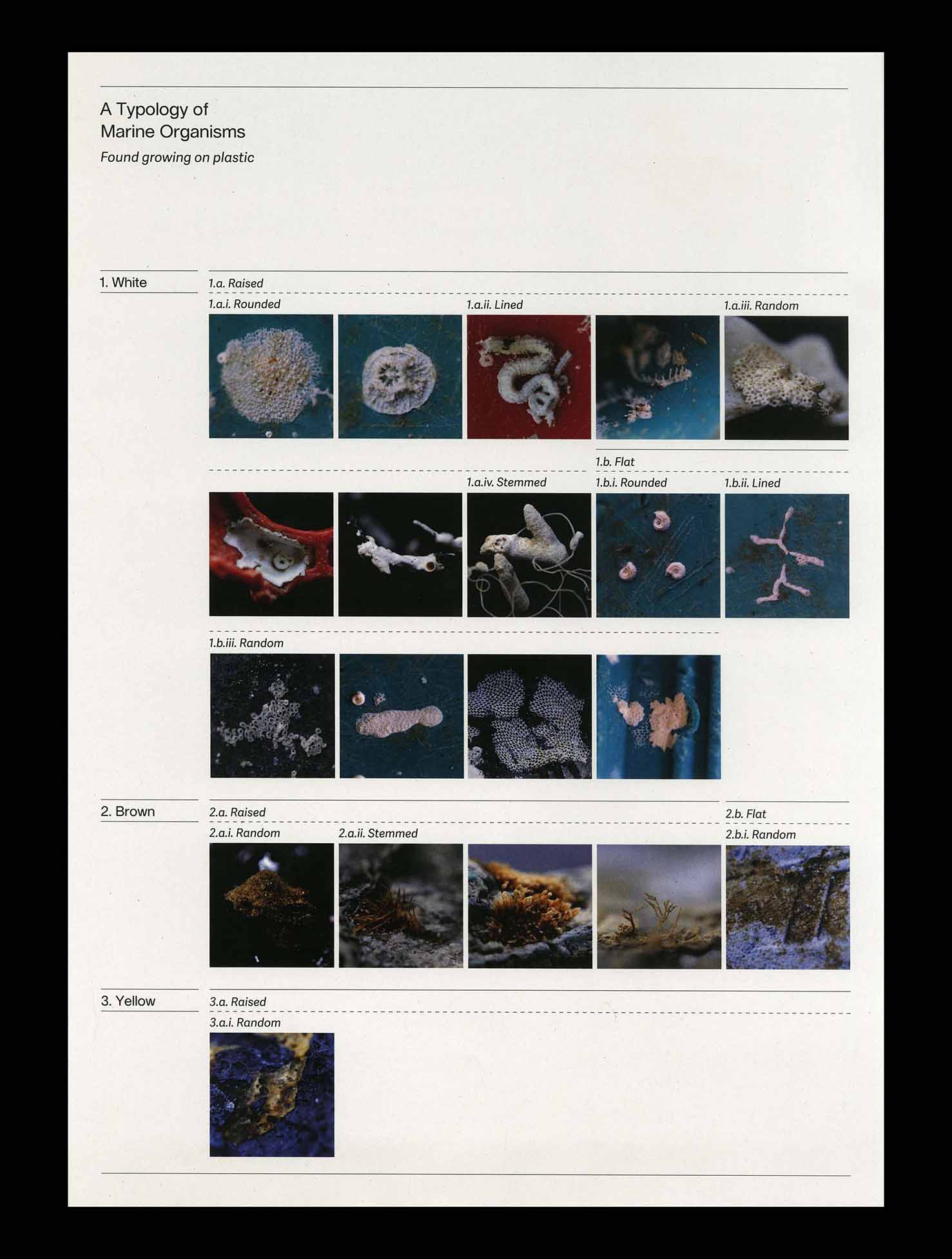

This experiment sought to highlight the often unseen ways that plastic and nature interact after disposal. It sought to communicate this phenomena as a way of promoting considerations of plastic as a material. This was executed through identifying the presence and diversity of marine growths found on the surfaces of the warped plastics.

Precedents

This experiment responded to the need for more obvious portrayals of the warped plastic from Experiment: A Visual Catalogue of Plastics.

Methods

The narrow gaze of the macro lens identified and captured these marine growths, and was used to visualise these categories. The outcome of this experiment (Figure 10) is referred to as a typology rather than a taxonomy as it compares and juxtaposes between formal types (colour, shape and form) rather than biological methods of internally taxonomising.

Reflection

Feedback for this outcome from supervisors was that it was too abstracted to be able to incite ecological thought from consumers. The use of a macro lens completely obscured that it was plastic that these growths were living on. It would require huge leaps of interpretation for consumers to move from looking at marine growths on plastic to considering the liveliness and longevity of plastic waste.

This was also in part due to the structured and ordered way these growths were presented, which hid the excitement and wonder that observing these plastics brought forth. My intentions of communicating the liveliness of plastic thus became subsumed by a preoccupation with identifying and categorising the marine growths found. This reliance on methods of analysing, ordering and categorising in this experiment—methods common to scientific fields—reflected an objective approach to the representation and treatment of plastics in this research so far. This made me realise that I was caught up in finding ‘facts’ about the plastic to establish order rather than focusing on visual strategies that would excite, unsettle and draw responses from consumers. Moving away from scientific lenses of visually presenting plastic was therefore necessary.

This was also in part due to the structured and ordered way these growths were presented, which hid the excitement and wonder that observing these plastics brought forth. My intentions of communicating the liveliness of plastic thus became subsumed by a preoccupation with identifying and categorising the marine growths found. This reliance on methods of analysing, ordering and categorising in this experiment—methods common to scientific fields—reflected an objective approach to the representation and treatment of plastics in this research so far. This made me realise that I was caught up in finding ‘facts’ about the plastic to establish order rather than focusing on visual strategies that would excite, unsettle and draw responses from consumers. Moving away from scientific lenses of visually presenting plastic was therefore necessary.

Insights

The process of engaging with the marine growths did, however, introduce understandings of the plastic as ‘alive’, capable of supporting life and as entrenched within natural ecosystems. This began to shift my understandings of Bennett’s concepts of liveliness as being more than the plastic changing, and is explored further in later experiments.

The reflections of this experiment also highlighted and inspired a turn towards more playful and imaginative portrayals of the plastic in order to move away from scientific and fact-based approaches.

The reflections of this experiment also highlighted and inspired a turn towards more playful and imaginative portrayals of the plastic in order to move away from scientific and fact-based approaches.

Experiment

Visual Analogies

Aims

To find less literal, and more playful and inviting ways of representing the warped plastics.

This was an exercise in observation and interpretation in order to find other ways of talking about these plastic forms besides reiterating what the eye could already see.

This was an exercise in observation and interpretation in order to find other ways of talking about these plastic forms besides reiterating what the eye could already see.

Precedents

This experiment responds to the reflections of Experiment: A Typology of Marine Organisms by turning to more playful and fictional representations.

Methods

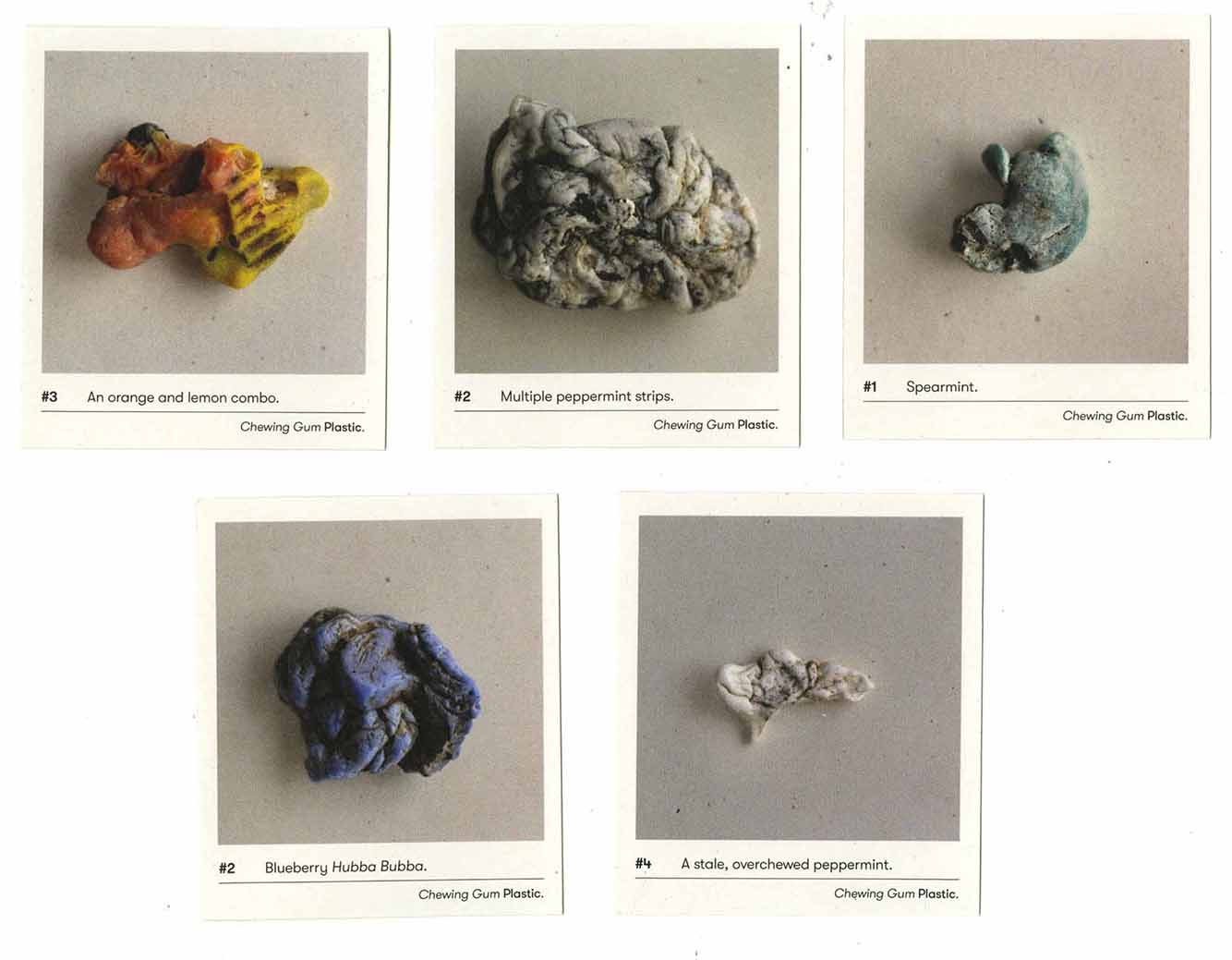

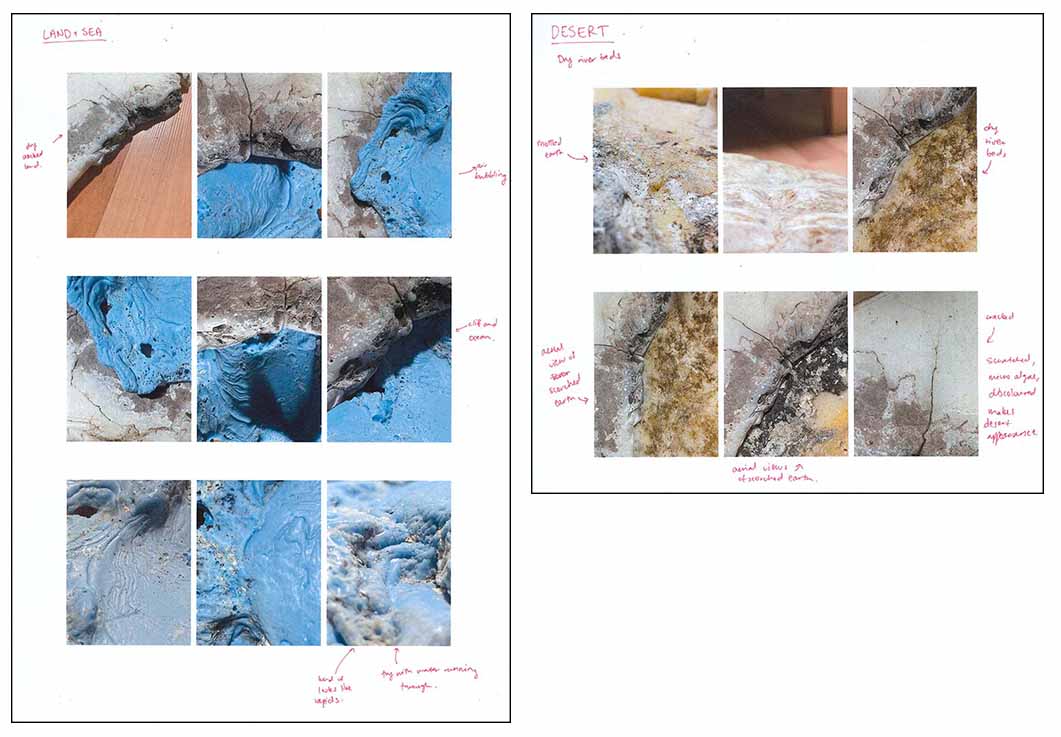

- The plastics looked like aerial views of natural landscapes (Figures 15–17)

-

The plastics looked like chewed up pieces of gum (Figure 12 & 13)

-

Plastics of different colours had warped to meld together (Figure 18)

Photography was used once again to capture and document these visual analogies—however, the photographs needed accompanying text to make the correlations I was forming obvious. My familiar practice of categorising and naming took over as I established labels for these associations.

Reflection

These outcomes resulted in a visual summary of things I had observed in the physical appearances of the plastics, but the significance of these analogies was unclear. At this point, I was letting my observations direct my inquiries rather than being guided by my research intent of finding visual stories to encourage ecological thought in consumers. Searching for new interpretations also highlighted that I had become familiarised to the warping of the plastics; they were no longer foreign or new to me, which is why I felt compelled to articulate and establish meaning for them. The visual impact of these warped plastics has a limit—the surprise and fascination that their ambiguity brings is short-lived.

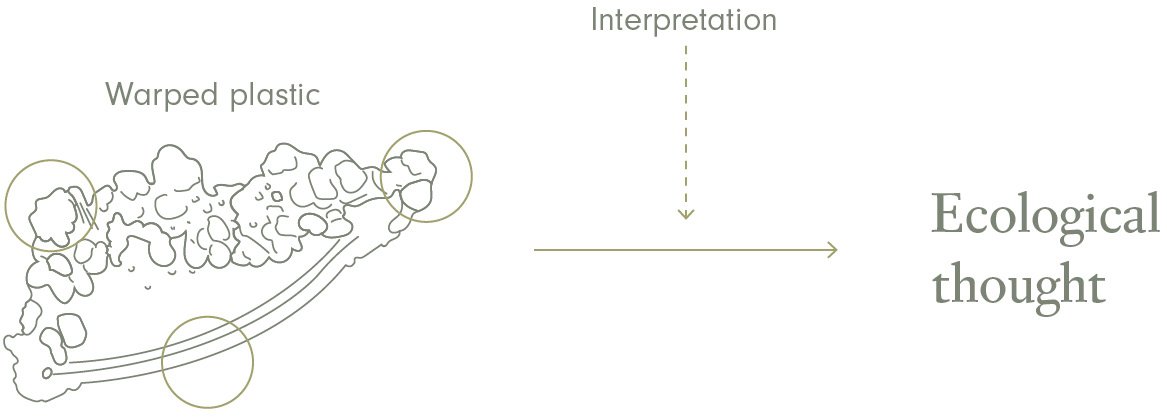

This experiment, however, did demonstrate a shift in approach compared to previous experiments. While previous experiments sought to document and re-present the warped plastics as a way of stimulating ecological thought in consumers (Figure 19), this experiment added a step to this process and recognised that there needed to be another level of interpretation and meaning attributed to these warped plastics in order to facilitate consumers reaching these ecological thoughts (Figure 20).

![FIGURE 19 Previous experiments assumed a linear approach for facilitating ecological thought.]()

![FIGURE 20 This experiment illuminated that ecological thought needs to be facilitated by more than just the visual of the warped plastics.]() This marked a shift in understanding how to communicate to consumers, and particularly, understanding that the visual impact of the warped plastics alone was not enough to automatically stimulate ecological reflections. It was my use of analogy, descriptive language and labelling that sought to attribute further meaning to these plastics.

This marked a shift in understanding how to communicate to consumers, and particularly, understanding that the visual impact of the warped plastics alone was not enough to automatically stimulate ecological reflections. It was my use of analogy, descriptive language and labelling that sought to attribute further meaning to these plastics.

My use of analogy and description reflected a need to understand these plastics and make them recognisable again. The forms of these plastics were so warped and foreign that analogies had to be used to be able to connect with and comprehend them through my human consumer eyes. This highlighted that we still need to be able to recognise and resonate with these plastics for any shifts in perceptions to occur—they can’t be completely decontextualised from human consumer realities or else they become nothing more than an object without meaning. The particular analogies chosen in this experiment, however, were perhaps not suitable for inspiring ecological thought in others.

This experiment, however, did demonstrate a shift in approach compared to previous experiments. While previous experiments sought to document and re-present the warped plastics as a way of stimulating ecological thought in consumers (Figure 19), this experiment added a step to this process and recognised that there needed to be another level of interpretation and meaning attributed to these warped plastics in order to facilitate consumers reaching these ecological thoughts (Figure 20).

My use of analogy and description reflected a need to understand these plastics and make them recognisable again. The forms of these plastics were so warped and foreign that analogies had to be used to be able to connect with and comprehend them through my human consumer eyes. This highlighted that we still need to be able to recognise and resonate with these plastics for any shifts in perceptions to occur—they can’t be completely decontextualised from human consumer realities or else they become nothing more than an object without meaning. The particular analogies chosen in this experiment, however, were perhaps not suitable for inspiring ecological thought in others.

Insights

The particular use of analogy in this experiment to imagine what these plastics could be saying (but not necessarily displaying) offered a path forwards in this research. It illuminated that I should be exploring how to actively frame and interpret the warping of these plastics, and to present these interpretations in ways that are meaningful and ecologically thought-provoking for consumers.