Part Three

What Now? Final Workshop results

In this section I detail the results of the What Now? Final Workshop to determine the impact of the workshop and its storytelling prompts on participants. Similar to Trial Workshop participants, the participants of this Final Workshop engaged in ecological and nonhuman considerations about plastic. I consider how prescribing custodianship of plastic onto participants and how mapping the deep future timelines of plastic particularly achieved this result.

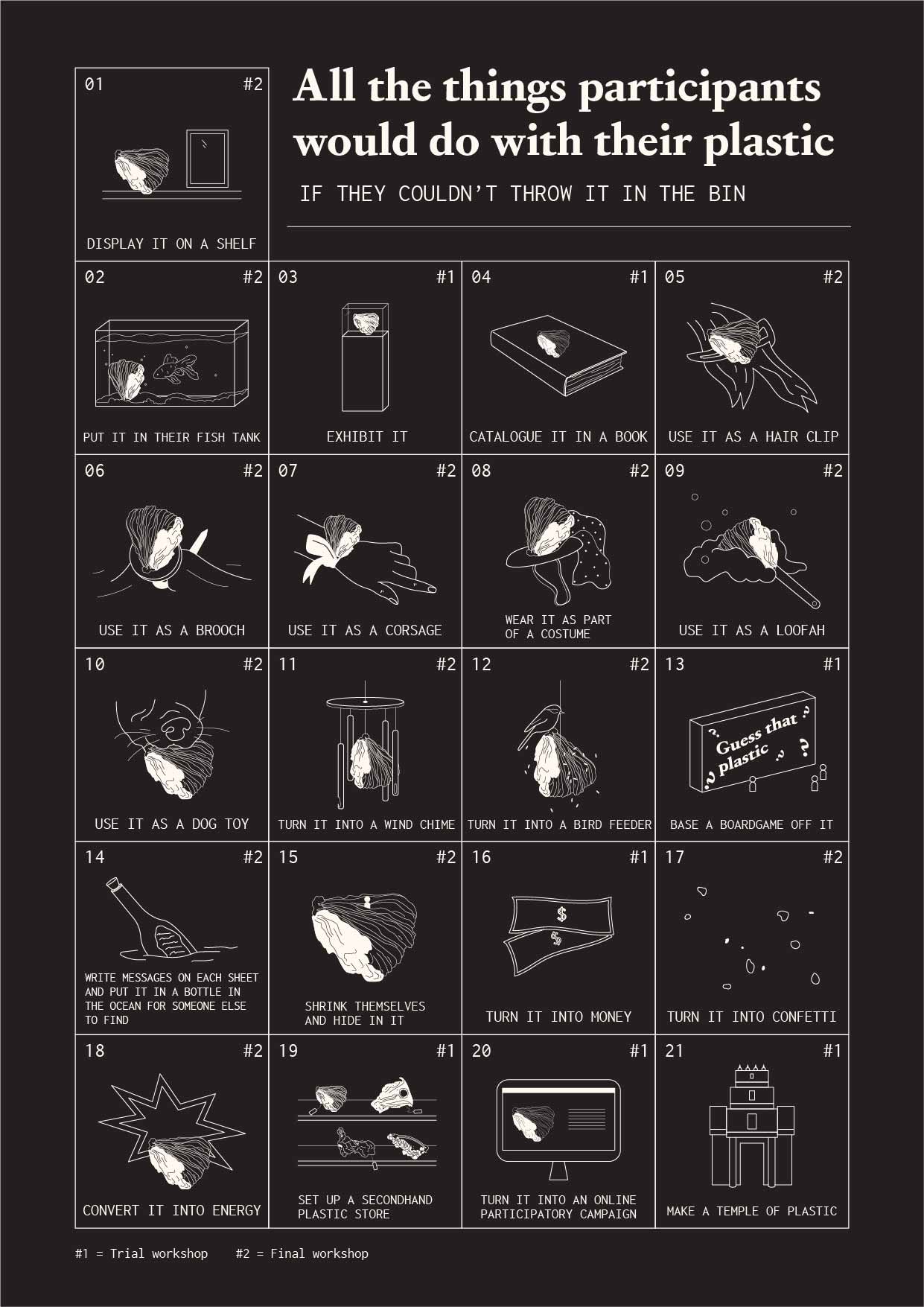

Participant responses to custodianship

Comparing the responses to custodianship between Trial and Final Workshops (Figure 78) reveals a range of responses to custodianship; from re-using their plastic for individual use (like the loofah) to re-using their plastic on a wider human scale (like converting it into energy or money). Their responses exist within fictional scenarios (jokingly discussed, and clearly never to be executed), which highlights how outside the norm this idea is and how difficult it is to give plastic another life.

“An aquarium with plastic building up on the bottom and then you go out and go ‘oh I forgot my KeepCup’, or that day you choose to buy lunch and go ‘oh why has this got so much plastic on it? I’ll choose that lunch.’” — Participant statement

The participants’ idea to use their warped plastic to change perceptions and facilitate ecological awareness strikingly mirrors both my own positions in this research and the responses of participants from the What Now? Trial Workshop. This similarity in thought demonstrates a commonality in response in wanting to use the warped plastics for ecological change, and also highlights that participants can interpret ecological messages within the plastic.

When prompted to consider what they would do with their plastic after this plan, however, one participant stated that they couldn’t keep maintaining custodianship of their plastic for that long:

“I’m not even emotionally attached to this even though we picked it out from there.”

— Participant statement

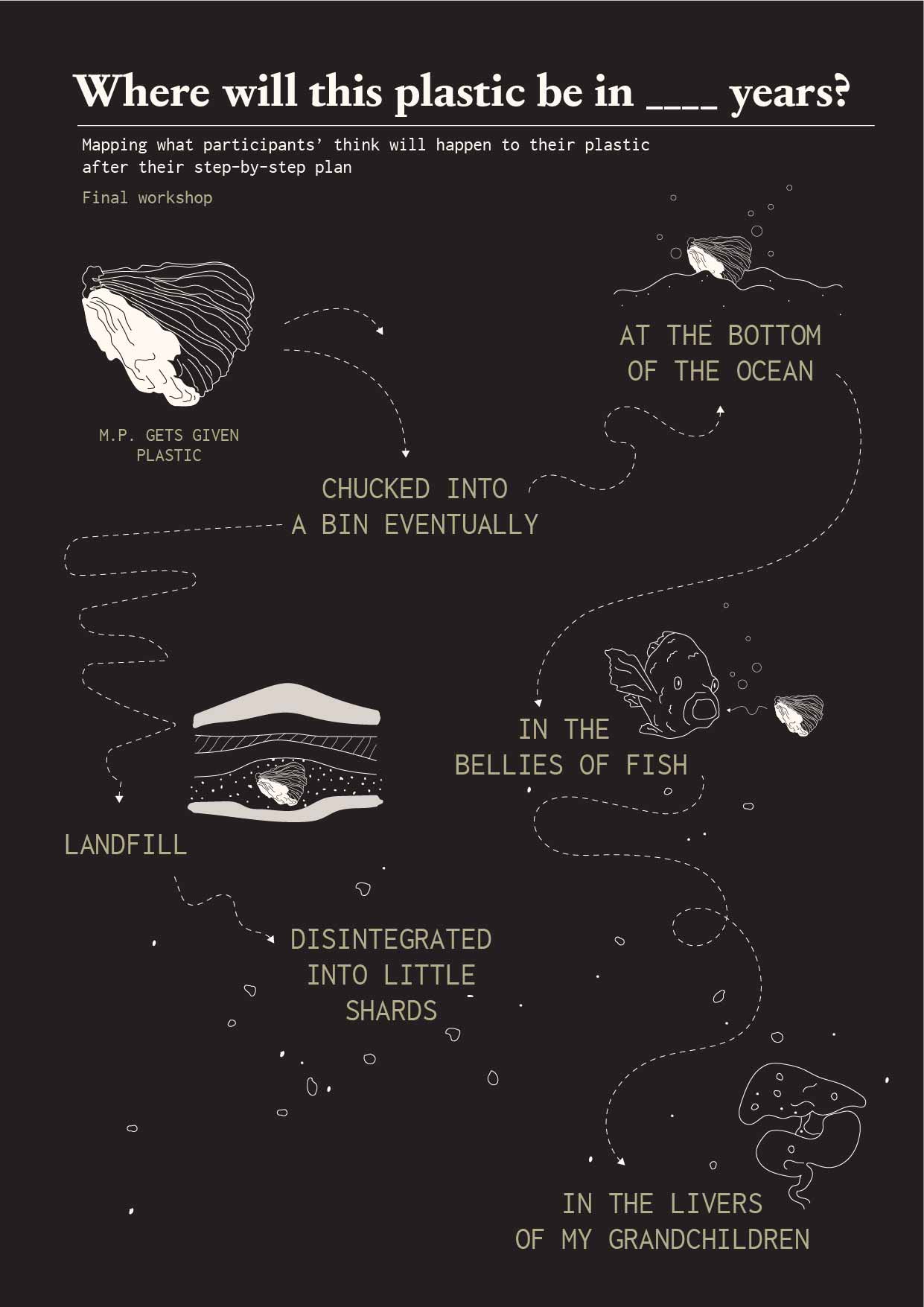

Their wish to eschew continued responsibility and custodianship of their plastic highlights just how difficult it can be to want to keep plastic and not dispose of it. It also highlights how custodianship made them anxious in realising how long they would need to keep maintaining the plastic for. Custodianship was hence effective in shifting participants to personally realise the longevity of plastic.

Participant responses to storytelling prompts

Participants, however, did initially display difficulty in answering these prompts, and began to segue to other topics. This was acknowledged by more than one participant, in realising that they did not answer the prompts fully:

“I noticed we sort of avoided some of your questions a bit because they’re so hard. ‘Where will plastic be in 100 years?’ and we just talked about stuff for a while. ‘Landfill, that’s where it’s going to be’.”

— Participant statement

Their initial avoidance of questions about the afterlife of plastic demonstrates that thinking about the multi-generational and persistent presence of plastic does not come naturally to participants, and that it is difficult to become de-centred from an immediate human reality.

Impact of the workshop on participants

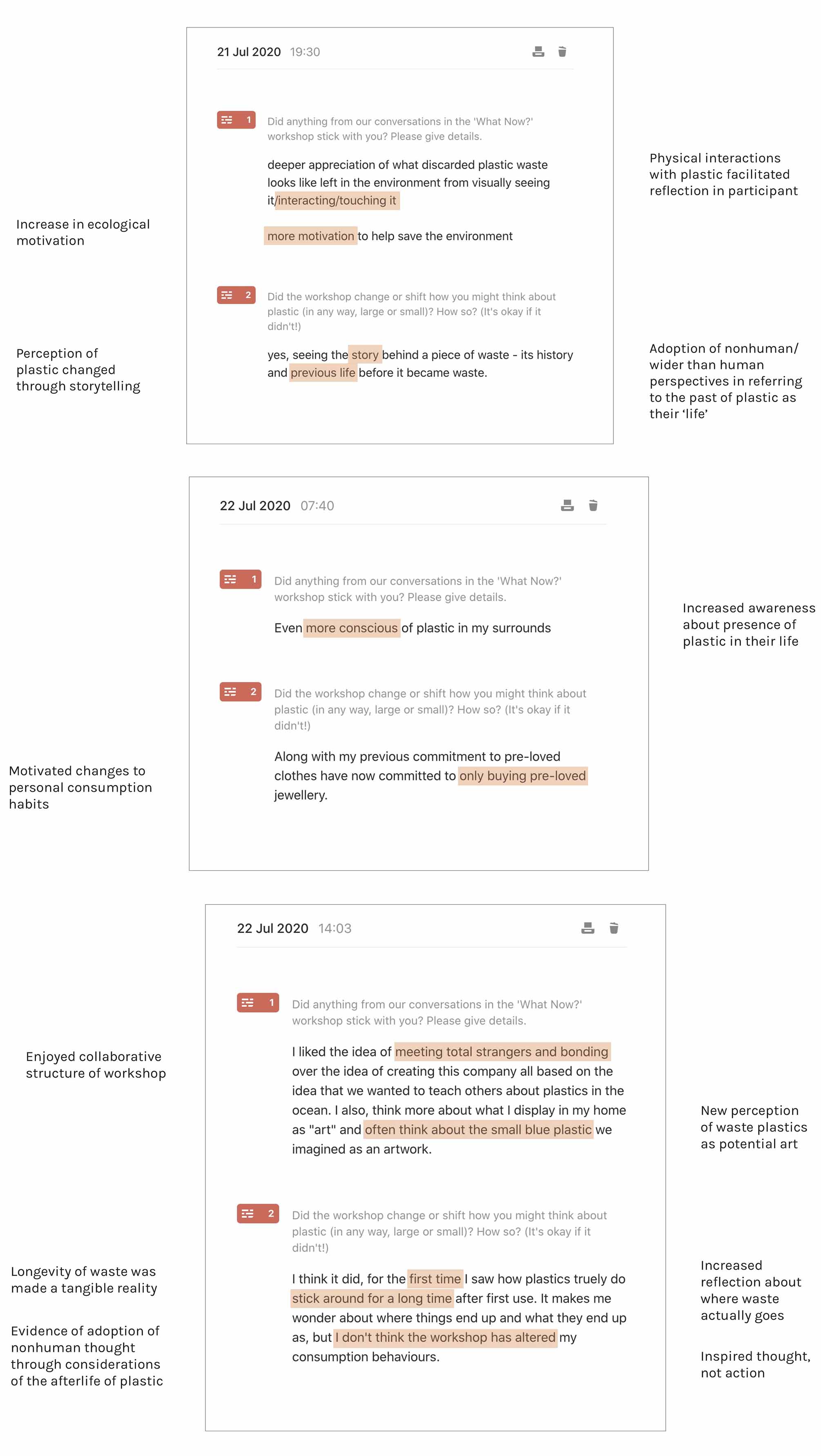

One participant was affected by interacting with the physical artefacts of the plastic and of considering the past life of these plastics, while another was affected by the discussions of plastic itself. The third participant was particularly affected by the collaborative nature of the workshop. This demonstrates how different elements of the workshop spoke to different participants.

Their responses also reveal that ecological thought was facilitated through the workshops. Two participants expressed an increased ecological motivation—with one participant in particular identifying changes they could make to their own consumption habits—while the third participant expressed increased ecological awareness and thought. These shifts, again, refer to general ecological changes rather than plastic-specific ones, further highlighting that conversations around plastic ultimately also lead to conversations around sustainability and environmentalism. Their responses reiterate that these workshops can facilitate either increased motivation to act or increased thought in participants.

Conclusion

The results of this workshop demonstrate that an understanding of the persistent afterlives of plastic was successfully facilitated through the nature of the prompts and workshop. This was attributed mainly to questions of time, which challenged the immediate worldviews of participants and led them to adopt nonhuman understandings of time.

What is interesting about this particular workshop is that unlike the previous Trial Workshop, not all participants perceived themselves as ecologically minded—one participant reflected during discussion that they were currently at the “first step” of ecological behaviour and that they had “only” bought a KeepCup the previous year. This illustrates that the collaborative and conversational design of the workshop can facilitate an awareness in participants about their own behaviours by bringing to light how others behave. It also reveals a potential third persona type amongst participants; the ‘Cautious’. Once again, Stoknes’ measure of social attitudes is referred to in the naming and classification of this participant type:

The Cautious

These individuals think plastic “is a problem, but are not certain. They have given some thought to the issue, but not extensively. They don’t view it as a personal threat, and don’t feel a sense of urgency to do much about it. Other concerns get a higher priority” (Stoknes, 2015, p. 58).

This is distinctly different to the values of the other participants in this workshop, who best align with personas of ‘Concerned’ and ‘Changemaker’.

What is interesting about this particular workshop is that unlike the previous Trial Workshop, not all participants perceived themselves as ecologically minded—one participant reflected during discussion that they were currently at the “first step” of ecological behaviour and that they had “only” bought a KeepCup the previous year. This illustrates that the collaborative and conversational design of the workshop can facilitate an awareness in participants about their own behaviours by bringing to light how others behave. It also reveals a potential third persona type amongst participants; the ‘Cautious’. Once again, Stoknes’ measure of social attitudes is referred to in the naming and classification of this participant type:

The Cautious

These individuals think plastic “is a problem, but are not certain. They have given some thought to the issue, but not extensively. They don’t view it as a personal threat, and don’t feel a sense of urgency to do much about it. Other concerns get a higher priority” (Stoknes, 2015, p. 58).

This is distinctly different to the values of the other participants in this workshop, who best align with personas of ‘Concerned’ and ‘Changemaker’.

Conclusions for What Now?

All participants from the What Now? workshops were shifted in some way—with their responses highlighting either a motivation to change actions or an increased motivation to think through topics of waste and consumption. This demonstrates that the workshop facilitated individual and personal change in participants. This workshop was therefore successful in its aim of bringing the longevity of plastic into the consciousness of participants through custodianship and nonhuman storytelling. The difference of results between participants of the Trial and Final Workshops, however, suggests that the design of these workshops had a different impact on each individual.

While the results of Stories from the Afterlife suggested that somewhat ecologically aware (Concerned)—but not too ecologically minded (Changemakers)—participants were most impacted by its designs, the same cannot be said for the participant most like the ‘Changemaker’ persona in What Now?. This ‘Changemaker’ participant—strongly ecologically minded and researching within the field of sustainability—was impacted by the workshop, unlike those with similar attributes in Stories from the Afterlife.

The difference between ‘Changemaker’ participants in each workshop may depend on how well-informed about the issue of plastic they perceive themselves to be. They can therefore be distinguished by how open-minded and willing they are to obtain different points of view. This is evidenced in the difference in responses between ‘Changemaker’ participants; Stories from the Afterlife ‘Changemaker’ participants stated that the workshop affirmed their own views about plastic, while the What Now? ‘Changemaker’ participant stated that they learned new understandings from the workshop. This once again raises the question of whether the amount of knowledge one possesses about plastic can narrow their worldview and hinder their ability to explore different framings of the problem. The evidence of this disparity means that an adjustment to the participant personas is required:

The Close-minded Changemaker

Refers to those who are well-informed about the problem of plastic and “convinced what is happening is human-caused, and feel it is a serious and urgent threat. The alarmed try to do something in their own lives and support aggressive national response” (Stoknes, 2015, p. 58). Individuals within this persona are researching or working within sustainable fields, and believe they have an extensive understanding of the issue. The result of this is a difficulty to explore perspectives that are alternative to theirs.

The Open-minded Changemaker

These participants are similarly well-informed and motivated as the ‘Changemakers’ above, and are researching/working within sustainable practices. The difference is that unlike the more close-minded or ‘veteran’ changemakers, the ‘Open-minded Changemakers’ still believe they have more to learn about the issue. They are thus open to both sharing and receiving other perspectives.

The Concerned

Identifies those who recognise plastic as a concern in their daily life and make small changes to their behaviours to contribute to the issue.

The Cautious

Are aware about the issue of plastic, but not well-informed about the scope and specifics of it. They have undertaken little, if any, personal response to the issue, but are open to change.

Of the four personas present during the workshops, it is the latter three which the workshops most effectively impacted.

While the results of Stories from the Afterlife suggested that somewhat ecologically aware (Concerned)—but not too ecologically minded (Changemakers)—participants were most impacted by its designs, the same cannot be said for the participant most like the ‘Changemaker’ persona in What Now?. This ‘Changemaker’ participant—strongly ecologically minded and researching within the field of sustainability—was impacted by the workshop, unlike those with similar attributes in Stories from the Afterlife.

The difference between ‘Changemaker’ participants in each workshop may depend on how well-informed about the issue of plastic they perceive themselves to be. They can therefore be distinguished by how open-minded and willing they are to obtain different points of view. This is evidenced in the difference in responses between ‘Changemaker’ participants; Stories from the Afterlife ‘Changemaker’ participants stated that the workshop affirmed their own views about plastic, while the What Now? ‘Changemaker’ participant stated that they learned new understandings from the workshop. This once again raises the question of whether the amount of knowledge one possesses about plastic can narrow their worldview and hinder their ability to explore different framings of the problem. The evidence of this disparity means that an adjustment to the participant personas is required:

The Close-minded Changemaker

Refers to those who are well-informed about the problem of plastic and “convinced what is happening is human-caused, and feel it is a serious and urgent threat. The alarmed try to do something in their own lives and support aggressive national response” (Stoknes, 2015, p. 58). Individuals within this persona are researching or working within sustainable fields, and believe they have an extensive understanding of the issue. The result of this is a difficulty to explore perspectives that are alternative to theirs.

The Open-minded Changemaker

These participants are similarly well-informed and motivated as the ‘Changemakers’ above, and are researching/working within sustainable practices. The difference is that unlike the more close-minded or ‘veteran’ changemakers, the ‘Open-minded Changemakers’ still believe they have more to learn about the issue. They are thus open to both sharing and receiving other perspectives.

The Concerned

Identifies those who recognise plastic as a concern in their daily life and make small changes to their behaviours to contribute to the issue.

The Cautious

Are aware about the issue of plastic, but not well-informed about the scope and specifics of it. They have undertaken little, if any, personal response to the issue, but are open to change.

Of the four personas present during the workshops, it is the latter three which the workshops most effectively impacted.