Experiment

Re/Collected

Aim

This experiment sought to use the assemblages of plastic observed at Eco Barge to subvert the ‘out of sight, out of mind’ mentality with which we dispose of plastic, and consequently promote considerations of the afterlife of plastic. It facilitated wider questioning and critique of how consumers don’t know what to do with their plastic waste, even waste collectors like Eco Barge. Humans do not have the capacity to mentally or technologically process this waste.

Precedents

I made these observations while at the Eco Barge site, where I noticed a large amount of assemblages of plastic distributed throughout the space. These plastics were too large and solid to be put through the plastic shredder which would turn them into pellets to be recycled—as explained by Fiona Broadbent, the volunteer coordinator at Eco Barge (personal communication, 21 March, 2019)—and had been tossed aside as a temporary solution, sitting outside amongst the trees and grass. To me, these gatherings of waste silently questioned, ‘what now?’.

This experiment used these assemblages as a method to manifest Bennett’s argument that being conscious of how waste persists after disposal might generate a considered ecological consciousness in consumers (2010, p. 4). It also responds to the reflections in Experiment: Dealing with Waste by exploring the afterlives of plastic outside fact-based lenses. The documentation of these assemblages draws from the in-situ style of photography present in Chris Jordan’s Midway: Message from the Gyre (2009-present).

This experiment used these assemblages as a method to manifest Bennett’s argument that being conscious of how waste persists after disposal might generate a considered ecological consciousness in consumers (2010, p. 4). It also responds to the reflections in Experiment: Dealing with Waste by exploring the afterlives of plastic outside fact-based lenses. The documentation of these assemblages draws from the in-situ style of photography present in Chris Jordan’s Midway: Message from the Gyre (2009-present).

Methods

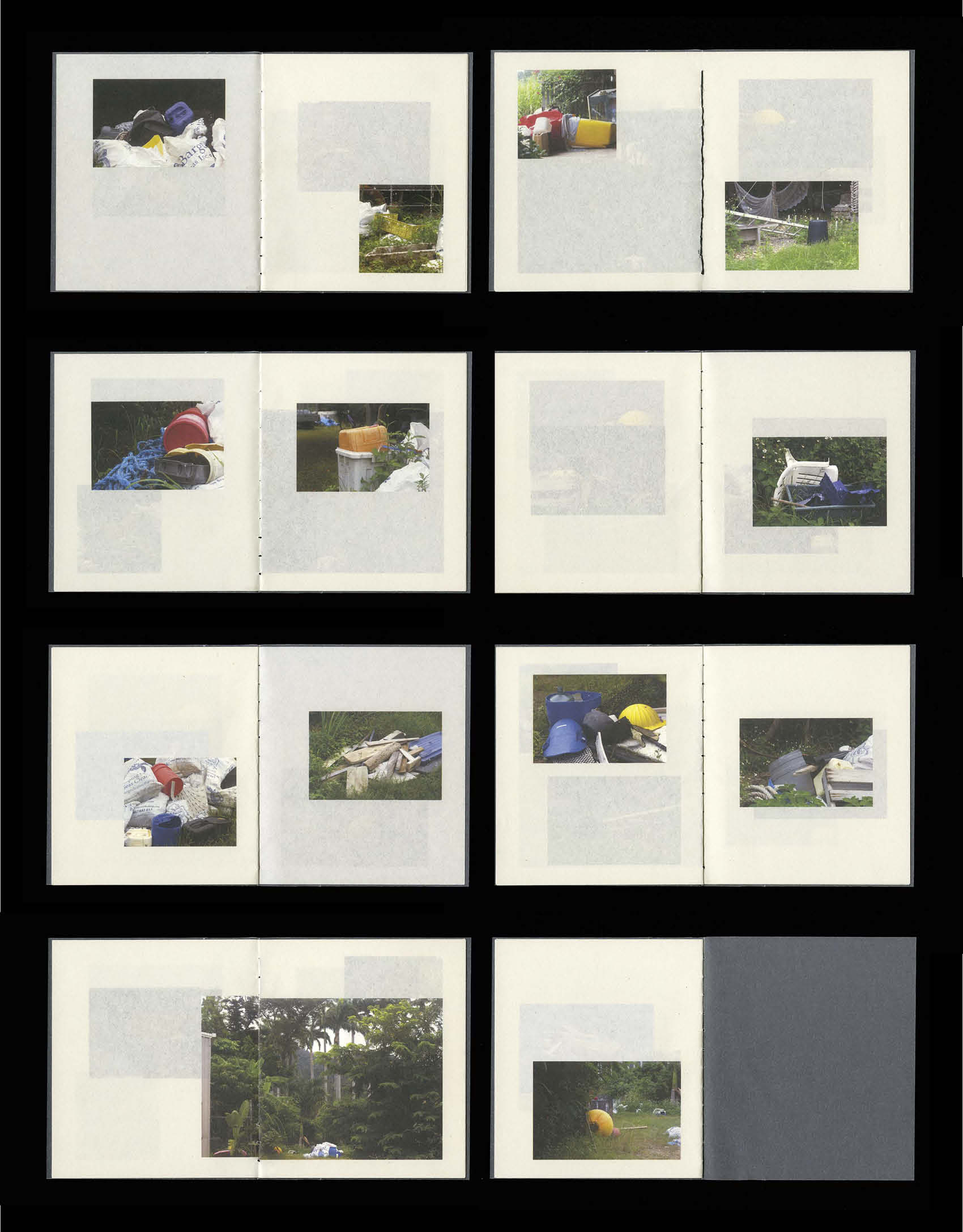

Adopting a sociologist’s approach, the assemblages were photographed in-situ to provide glimpses of the post-disposal lives of plastic (as opposed to previous experiments, which objectively documented plastic as a phenomena). Framed amongst the greenery of grass and trees, the extremely solid and seemingly permanent material properties of plastic juxtaposed against the natural, more easily decaying environment, and highlighted that it would be impossible for the plastic to break down. From this, a story was formulated about the plastic as being forgotten and enduring ‘forever’ in this condition.

These photographs were organised sequentially into a book format—a form recognisably used to house stories—to highlight that there is a story to these photographs (Figure 30). The use of generous white space in the book’s composition, as well as my decision to include long shots of the plastic in nature, served to generate a feeling of great stillness, and to perpetuate this unsettling notion of plastic persisting forever without end.

These photographs were organised sequentially into a book format—a form recognisably used to house stories—to highlight that there is a story to these photographs (Figure 30). The use of generous white space in the book’s composition, as well as my decision to include long shots of the plastic in nature, served to generate a feeling of great stillness, and to perpetuate this unsettling notion of plastic persisting forever without end.

Reflection

The abandoned assemblages at Eco Barge shifted my point of view to imagine what these plastics were potentially ‘feeling’ in their abandoned state. This de-centred me as a human, as it made me attune to recognising that there are other perspectives in existence besides my own human one—and that plastic waste can be one of these nonhuman perspectives. This realisation anthropomorphised the pieces of plastic, allowing me to recognise their agency and liveliness, and that they are entities that existed with and outside of humans.

The adoption of anthropomorphism as a lens was a powerful way of beginning to create a perception of plastic as more than a disposable consumer by-product. Shifting the point of view used in previous experiments from that of a human (me) talking about plastic, to that of imagining what plastic experiences, inspired a speculative consideration of what happens to plastic as an entity that can experience life after disposal. I found the adoption of this lens particularly successful in its ability to make me question where my own plastic waste is now, and also in its ability to encourage me to consider how I might feel under the same conditions as waste.

These assemblages—and my interpretation of them as anthropomorphic—expanded upon the ideas of time from Experiment: Fossilised Plastic. Thinking of the plastics as abandoned raised questions about whether they would ever be removed, or if they would just continue to persist in that space forever without end. This deeply unsettled me as it highlighted the deep time span that plastics can operate at, and had the effect of making me realise how insignificant my own lifespan is compared to that of plastic. Being conscious of how plastic persists after disposal at a timescale incomprehensible to humans—and in environments away from human eyes—facilitated recognition of the other realities outside of my own; where things do experience life, although differently. This also re-conceptualised understandings of time for me, and made it apparent that time exists outside of and beyond humans. Other entities such as plastic, then, are not constrained within human timescales and continue living and existing regardless of humans. The assemblages of plastic, and the story they presented, thus provided me with the ability to access and understand Colebrook’s ideas of the “other timelines, other points of view and other rhythms” (2013, p. 60) outside the human. This strengthened my sense of ecological responsibility, as it made tangible how the effects of plastic consumption reverberate at a nonhuman scale; a scale where humans cannot control and undo the damage.

This experiment hence also facilitated a new interpretation of Bennett’s theories. My previous understanding of Bennett’s concept of ‘liveliness’ (2010) as referring to materials that can warp, change and adapt evolved though this experiment to include consideration of things as capable of existing and experiencing life through time. This demonstrates how practice can inform and shift conceptual understandings of theory. It also highlights how storytelling around nonhuman (or more-than-human) concepts of time can be used as a method for facilitating ecological concern.

While not a conscious decision at the time of undertaking this experiment, the small size of this publication (approximately 11cm x 13cm) can also be seen as an attempt to establish feelings of ‘cuteness’ in viewers. This borrows from aesthetic theorist Sianne Ngai’s statement that things which are small in size can “evoke tenderness” and paints the subject in need of protection (2012, pp. 3-4). This highlights that my design decision to work in small scales may have been an intention to create empathy and concern for the plastics (not just about plastic). This demonstrates that the material form of these outcomes can be used to influence perceptions and interpretations of the subject. The evaluation of this experiment—formulated in hindsight through reflection—also demonstrates how reflective practice can synthesise the learnings from critical theory, and thereby inform design practice.

The adoption of anthropomorphism as a lens was a powerful way of beginning to create a perception of plastic as more than a disposable consumer by-product. Shifting the point of view used in previous experiments from that of a human (me) talking about plastic, to that of imagining what plastic experiences, inspired a speculative consideration of what happens to plastic as an entity that can experience life after disposal. I found the adoption of this lens particularly successful in its ability to make me question where my own plastic waste is now, and also in its ability to encourage me to consider how I might feel under the same conditions as waste.

These assemblages—and my interpretation of them as anthropomorphic—expanded upon the ideas of time from Experiment: Fossilised Plastic. Thinking of the plastics as abandoned raised questions about whether they would ever be removed, or if they would just continue to persist in that space forever without end. This deeply unsettled me as it highlighted the deep time span that plastics can operate at, and had the effect of making me realise how insignificant my own lifespan is compared to that of plastic. Being conscious of how plastic persists after disposal at a timescale incomprehensible to humans—and in environments away from human eyes—facilitated recognition of the other realities outside of my own; where things do experience life, although differently. This also re-conceptualised understandings of time for me, and made it apparent that time exists outside of and beyond humans. Other entities such as plastic, then, are not constrained within human timescales and continue living and existing regardless of humans. The assemblages of plastic, and the story they presented, thus provided me with the ability to access and understand Colebrook’s ideas of the “other timelines, other points of view and other rhythms” (2013, p. 60) outside the human. This strengthened my sense of ecological responsibility, as it made tangible how the effects of plastic consumption reverberate at a nonhuman scale; a scale where humans cannot control and undo the damage.

This experiment hence also facilitated a new interpretation of Bennett’s theories. My previous understanding of Bennett’s concept of ‘liveliness’ (2010) as referring to materials that can warp, change and adapt evolved though this experiment to include consideration of things as capable of existing and experiencing life through time. This demonstrates how practice can inform and shift conceptual understandings of theory. It also highlights how storytelling around nonhuman (or more-than-human) concepts of time can be used as a method for facilitating ecological concern.

While not a conscious decision at the time of undertaking this experiment, the small size of this publication (approximately 11cm x 13cm) can also be seen as an attempt to establish feelings of ‘cuteness’ in viewers. This borrows from aesthetic theorist Sianne Ngai’s statement that things which are small in size can “evoke tenderness” and paints the subject in need of protection (2012, pp. 3-4). This highlights that my design decision to work in small scales may have been an intention to create empathy and concern for the plastics (not just about plastic). This demonstrates that the material form of these outcomes can be used to influence perceptions and interpretations of the subject. The evaluation of this experiment—formulated in hindsight through reflection—also demonstrates how reflective practice can synthesise the learnings from critical theory, and thereby inform design practice.

Insights

This experiment reveals that recognition and awareness of nonhuman timelines and realities—of consideration of a world wider than humans—can facilitate ecological reflection about my own actions of consumption and disposal. This highlights that shifting consumers to consider the nonhuman is an aim to continue to explore and work towards. It also illuminates that lenses of time are effective in facilitating ecological understandings of the longevity of plastic.

Anthropomorphic speculation about the afterlives and deep time lifespans of plastic provided the ability to access and tangibly recognise these nonhuman worlds. The creation of anthropomorphic, time-based and speculative stories are thus continued as a way of exploring and visualising the nonhuman longevity of plastic.

While this experiment successfully changed my own perspective to consider the nonhuman worlds plastic operates in, this was a result of making and firsthand experience. I questioned whether viewing this experiment would have the same effect on other consumers. More experimentation was needed to explore how to present these stories in ways that would successfully engage consumers.

Anthropomorphic speculation about the afterlives and deep time lifespans of plastic provided the ability to access and tangibly recognise these nonhuman worlds. The creation of anthropomorphic, time-based and speculative stories are thus continued as a way of exploring and visualising the nonhuman longevity of plastic.

While this experiment successfully changed my own perspective to consider the nonhuman worlds plastic operates in, this was a result of making and firsthand experience. I questioned whether viewing this experiment would have the same effect on other consumers. More experimentation was needed to explore how to present these stories in ways that would successfully engage consumers.